SUBSCRIBE TO THE PODCAST

Helping to prevent and treat the life-threatening complication of ICU delirium is one of your most important missions in the ICU. Let’s dive deep into everything you need to know about ICU delirium.

Episode Transcription

Ok, let’s talk about some hard and important things- starting with delirium. Your loved one is at risk of developing ICU delirium. One of your most important tasks as a loved one in the ICU is to protect your loved one from delirium. To do so, you need to understand what it is.

Delirium is actually acute brain failure. What does that mean? It means the brain is suddenly not functioning properly. It is an organ failure. What are the signs of delirium? How do you know if your loved is having this brain failure? I suspect that you, as the person that knows them best, will detect delirium sooner than anyone else.

There are two different types of delirium: hypoactive which is when they won’t wake up, are confused, profoundly lethargic, fall asleep as soon as they wake up, or even totally unresponsive to your yelling and shaking. Or, there can be hyperactive delirium in which they are confused, have short attention-span, sudden mood swings, agitation, combativeness, disorderly thinking, indirectable, and so on. Patients can swing between the two types of delirium and have anything in-between. When they are not themselves- you will know- usually.

Please understand, that though this happens in up to 81% of ICU patients, It is actually an emergency and can be life threatening.

In truth, delirium increases their chance of dying in the hospital by two times and triples their chance of dying 6 months after discharge. Even after that, they’re still at higher risk of dying 1 year after discharge. For every 1 day of delirium, there is a 10% increase in risk of dying.

Patients with delirium are likely to spend far more time in the ICU and the hospital as well as discharge to a care facility instead of home after the hospital.

So what is causing this and what is going on to make your loved one become a different person or not even recognize you? Lots of things.

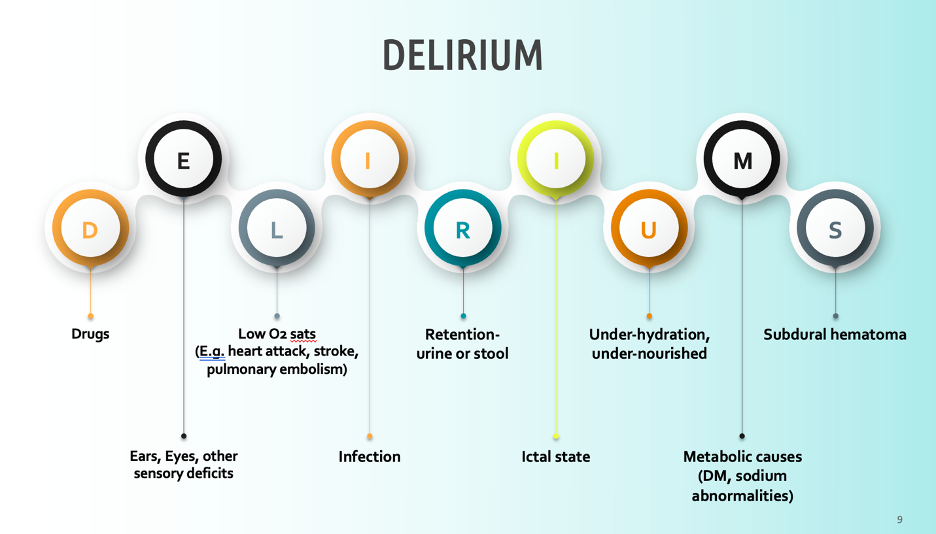

There can be numerous causes of delirium – this can be lined out in the acronym DELIRIUM- I can a cute little diagram on the blog.

D is for drugs- this can be street drugs, withdrawal from drugs, or can be the drugs given in the ICU. Next episode we will dive into sedation. For now, please know that this is a HUGE risk factor and often avoidable. This is where you come in to advocate for the avoidance of drugs that cause delirium. Again, next episode we’ll get deep into that.

E is for ears and eyes- sensory deficits. If you loved one has hearing aids or glasses, make sure they’re with them and on. Not being able to hear or see well in the ICU can really lead the brain to fail while it’s already under so much stress.

L- is for low oxygen saturations. So anytime the lungs are struggling and the body isn’t getting enough oxygen, OR there is something preventing adequate blood flow like a heart attack or blood clots. When the brain doesn’t get enough oxygen, it can get injured and fail.

I – When the body is fighting an infection, it can be experiencing a significant inflammatory response which can really impact the brain function. There is a later episode about sepsis that will explain more about this. Just know that if your loved one is fighting an infection, it’s game time for you. Be on leery of sedation and be ready to implement the prevention strategies we’re about to discuss. Infection should have you on edge ready to fight for your loved one’s brain.

R- retention of urine or stool. If you love one is constipated, be concerned. This can affect their brain.

I-ictal state- if your loved one is having seizures, they are at risk of being delirious afterward. Be aware of how the ICU team responds to their agitation and confusion. Help your loved one stay calm and safe if they come out of a seizure lost and confused. Avoid sedation if they are not having active seizures. We will discuss this more.

U is for Under-hydration, Under nourishment- Dehydration and malnourishment are going to affect your loved one’s brain function. To be honest, we’re pretty good about giving fluids in the hospital, but can be really behind at making sure patients have adequate nutrition. Don’t hesitate to request a consultation with the ICU registered dietitian.

M- is for metabolic derangements- so if their sodium or glucose levels and such are off, this will affect their brain. If this is happening, hang with them. Keep them safe and utilize tools for delirium that I’ll share. Give sedatives during these episodes or causes will not fix delirium but will prolong it. Keep them safe while the team addresses the metabolic problems.

S- can be for subdural hematoma. When there is bleeding and swelling in the brain, the stress and pressure can affect it.

Ok, that was a lot of information. Clearly there are a lot of things we cannot control in the ICU. There is no magic wand to make many of those causes of delirium to go away. Yet, how we prevent and respond to delirium will greatly impact their survival and their quality of life after this hospitalization. Patients that suffer delirium are at high risk of having post-ICU PTSD and post-ICU dementia.

When patients are agitated, thrashing, and difficult to control during delirium, we as the ICU community are inclined to give them sedation. It makes them quiet, they look more comfortable, and they seem safer. We are culturally trained to believe that is the most humane approach. The problem is, that we’re giving something that causes the problem they’re having, which is : acute brain failure. If you go to an ICU survivor page, most of what they are discussing is the psychological trauma they experienced in delirium- often under medically induced comas.

I asked survivors to leave a google voicemail sharing what they experienced under sedation. I didn’t say anything about “hallucinations or delirium” – I just asked what they experienced in their medically induced comas. What they shared is found in Episode 4 on my other podcast, “Walking Home From the ICU”. If you want survivor perspective of what it is like in medically-induced comas and in delirium, I invite you to listen to episode 3, 4, 7, 78, 87, and 92. The following is a clip from one of the survivors:

“My hallucinations while under sedation were mostly nightmares, revolving around suffering, abandonment, and general mayhem. Some of the nightmares were recurring. These are just a few examples that I can recall with clarity. During my four week coma one nightmare which troubled me for a long time after recovering was the kidnapping Have my two young daughters, I would get close to finding them, only to discover they had been moved on. And I would always be one step behind the feeling of despair and hopelessness and this nightmare felt so real.

When they visited me in the ICU on the day after waking from the coma, I was in tears seeing them walking towards my bed. I still clearly remember them, asking their mother why I was crying. In another scenario, I was at a hospital when gunmen started attacking the building. And I remember running in fear, and physically feeling the bullets hitting me as they fired their guns.

When I awoke from the coma, I thought I was there because I’d been shot. I often wonder if the physical feeling of the bullets entering my body was caused by the procedures being performed on me while in the coma, like being put on ECMO, having chest drains, inserted, the Truckee ostomy blood draws, etc.

I also recall the feeling of solitude and isolation. In what I can only describe as a white space of nothingness. I would hear voices that were familiar to me. But I couldn’t place who it was talking. And wherever I looked, I couldn’t see anyone. As the voice was always behind me and out of sight. This would lead to an overwhelming sense of frustration, agitation, and loneliness that seemed tangible. Looking back, I believe I was hearing my parents, children or partner talking to me, this tells me that there is a certain level of consciousness while in the coma. But the brain is unable to correctly interpret events in the surrounding environment.”

I share this difficult insight with you so that you understand that the agitation and anxiety is likely because they are experiencing some deeply terrifying things. I say experiencing, because imagining, or having hallucinations or delusions is NOT appropriate terminology here. Where they are is REAL to THEM. The scenarios, the people, the feelings, terror, pain, and so on are more real than the room you’re looking at right now. THIS is why it causes PTSD. They have sincerely lived this alternative reality and suffered the stress, fear, and trauma of such events. This can affect how they sleep, cope, respond to normal life after the ICU. Debilitating depression, anxiety, and panic attacks are often the result of ICU delirium. It’s like bringing home a war veteran- especially if they already are one. The more trauma they had before the ICU, the higher risk they run of having post-ICU PTSD. If you want to hear about what it like to live with post-ICU PTSD from delirium during sedation in the ICU, listen to episodes 8, and 50-52. The more delirium is prevented and shortened, the better chance they have of going home the same person that came in.

Delirium, as acute brain failure, can cause long-term damage that changes how the brain works. Permanent cognitive impairments called “post-ICU dementia” can result from delirium. This can mean the ability to process and remember information is impaired, response time is delayed, fine motor skills are impacted, attention is disrupted, and executive function is altered for years after the ICU. Delirium survivors have explained to me that this has taken away their ability to drive, work, read, and enjoy certain interests they loved before the ICU. This gravely impacts their careers and can lead to early retirement. Interpersonal relationships are changed as their capacity and even identity is taken away from them and new stressors result from their disability. You can hear survivors share what living with post-ICU Dementia is like in episode 6. Links to these episodes are provided in the blogpost.

I tell you this because I deeply care and respect your right to know. I also sincerely believe you can do a lot to prevent and treat delirium. There is no medication for delirium. The only way to prevent and treat is:

- Avoiding medication that causes it- we’ll discuss sedation next episode

- Sleep

- Family

- Mobility

Let’s talk about those in the context of what you can do.

First- sleep:

Everyone has to sleep. You need to sleep so you can help your loved one. They need to sleep to keep their brains straight. Especially at night. You know your loved one. You know how they sleep. Do they use a certain pillow, blanket, white noise? Do they like it hot? Cold? Do they need a foot massage or relaxation techniques to prepare to sleep? Do they use a medication for sleep at home? Have they every responded poorly to sleepaids in the past? Do they have certain rituals that they do before bed like listening to a book, washing their face a certain way, or brushing their hair? Whatever idiosyncrasies belong to their unique night-time rituals- try to keep it as normal as if they were home. Bring that lavender lotion, the white noise machine, the blanket. Give that foot massage.

Talk with the ICU team about finding ways to do all of their cares at once. It’s the ICU, so things can change, emergencies happen, and a quiet night can be impossible. Yet, there are things we can usually do if a patient is a little more stable to give them the best chance possible for sleep. If they need a bath- 2 in the morning is not an acceptable time for that. Do it at 9 or 10pm if it has to be done on night shift. Offer to help if they are overwhelmed at that time. Ask what labs need to drawn in the morning and if they can wait until 7 am instead of 4 am. Ask what medications are scheduled during the night and if they can be given earlier or later to allow for a longer window of sleep. During rounds, or interactions with the intensivist, NP, or PA, ask if they think melatonin is appropriate for them to receive at night. If they’re not getting sleep, make the team aware and see if they want to order light sleeping medication- but not benzodiazepines or other sedatives that cause delirium.

In the pre-covid times, the “Awake and Walking ICU”, did not have visiting hours. Outside of COVID, there is rarely a time in which families should not be there. In general, only during sterile procedures or hostile situations that families have created- should families be kicked out of the ICU. If allowed, have someone stay with your loved one. If you are the only one involved in supporting them during this hospital admission and you are not the kind to be able to sleep on the recliner in the room, don’t torture yourself and run yourself ragged. Go home- sleep. I have seen family members develop their own version of ICU delirium after fragmented sleep during miserable nights. I have experienced it myself during my daughter’s hospitalizations. I stay- I understand if you do. I also support you if staying overnight is not going to allow you to have self-care. Your loved one needs you to keep yourself together right now. Figure out what will work for you guys to allow for sleep for everyone.

This leads me to the point about family as an intervention for delirium. You are one of the most powerful tools to keep them grounded in reality. Imagine when their brain is under so much stress- pain, infection, disrupted sleep, and in a totally unfamiliar and scary setting. You are what is familiar, safe, and comforting. You can help protect them from unnecessary sedation, help them sleep, and help them mobilize with the ICU team. A recent study showed that family presence for more than 2 hours a day decreased the risk of delirium by 88%.

If they are experiencing delirium, you can be the safe person to re-orient them, tell them where they are, and what’s going on. You can help keep them in bed and keep their lines, and tubes in. You can help distract them with activities, conversations, or diversions that you know they will like to keep them engaged with reality and mentally stimulated. You can help them communicate have their needs be known and met. We’ll discuss that more in the communication episode. Being isolated alone in the same room for days to weeks or separated from human connection in a medically-induced coma will make anyone lose their minds. You can keep them going. You can give them reason to keep fighting to live.

In the “Awake and Walking ICU”, there was a COVID patient that suffered the universal “COVID isolation” while awake on the ventilator. His lungs became so sick that he struggled to maintain to provide adequate oxygen to his body even on the highest ventilator support. Per difficult hospital policy, family was not allowed to be with him unless he was dying.

My colleague really really thought he was going to pass away. The family came in to say their goodbyes. My colleague left that shift assuming it was the last time she would see him. She came back a few days later to find him off the ventilator and breathing on his own and stable. She was shocked. She said to him, “I am so happy you’re still here. We were so convinced you were dying that we brought your family in.” He said, “I needed them. I needed my family. They kept me here”. There is no way to physiologically explain how his lungs improved so quickly over such a short amount of time… but he was convinced that it was his family.

I’m not sure what all I can say about visiting hours. Honestly, I hate them. I think they’re unethical, dated, and entirely unhelpful. I will also say that patient care and outcomes are usually improved when family is present. You are part of the ICU team. If it was my loved one… I would be deadset on being present for more than a few hours a day. If my loved one had delirium and was I only allowed to be there briefly… I would be bringing the research into the conversation. I would insist that the ICU team cannot treat this acute brain failure without family present. It is not unreasonable to suggest that a life-threatening condition such as delirium is not being treated when the family is locked out of the ICU. Removing family is failing to practice evidence-based medicine. That’s probably as much as I can publicly say.

Lastly, but not least: mobility. We will dive deep into this in another episode, but mobility is a life-saving intervention in the ICU. There are very few exceptions in which a patient cannot and should not be mobilized. Again, very few. We’ll talk later about what is “normal” and “cultural” in the ICU vs. what is best practice. Just know, that mobility not only helps the physical function, but the brain as well. That same study of delirium in Brazil also showed that mobility decreased odds of delirium by 95%.

Sitting in a chair during the day, standing, walking, doing squats, trying to keep the brain and body as connected and engaged during the day is powerful in preventing and treating delirium. Make sure your loved one has a physical and occupational therapy consultation- especially if they’re on the ventilator. This will help them sleep better and longer at night, prevent and treat anxiety and agitation, and decrease their time in the ICU and hospital among many things. Keep them active- even if that means arm bands, leg bike, leg raises, whatever exercises in the bed and chair that you can support them in even when the nurse and therapists are unavailable. You can help them tremendously by keeping them moving. One study showed that walking at night improved sleep and prevented delirium in the ICU. Make that part of the night routine with your ICU team.

In the end, ICU delirium is a life-threatening condition that can results in patients being twice as likely to die. Your presence at their side is an evidence-based treatment for this acute brain failure. Family presence can decrease the risk of delirium by 88%. If you are not at the bedside, acute brain failure is not being prevented or treated with all effective tools possible.

This was enough for one episode. Next episode we’ll talk more about the some of the cultural and educational barriers among ICU clinicians that make delirium prevention and treatment so difficult. I share this with you so that you are prepared to be proactive right away. This is one of your most important tasks for your loved one. Prevent and treat delirium. Good luck. I’ve attached some great resources as well as a list of episodes and interviews dedicated to delirium that are on my other podcast all on the blog. I’m here for you. Keep listening.

Notes:

-

Links to mentioned episodes:

Episodes with Survivor Testimonials:

https://anchor.fm/walkinghomefromtheicu/episodes/Episode-3-DNS-Do-NOT-Sedate-Me-eau564

https://anchor.fm/walkinghomefromtheicu/episodes/Episode-4-Sedation-is-NOT-Sleep-eb14er

https://anchor.fm/walkinghomefromtheicu/episodes/Episode-6-Broken-Brains-eb3tpc

https://anchor.fm/walkinghomefromtheicu/episodes/Episode-50-The-Reality-of-Post-ICU-PTSD-eitr2l

https://anchor.fm/walkinghomefromtheicu/episodes/Episode-52-Haunted-Beyond-the-ICU-eli508

https://anchor.fm/walkinghomefromtheicu/episodes/Episode-78-Never-Really-Over-e14jq5k

https://anchor.fm/walkinghomefromtheicu/episodes/Episode-81-Choose-Wisely-e160v5o

Extra episodes on Delirium:

https://anchor.fm/walkinghomefromtheicu/episodes/Episode-51-Post-ICU-PTSD-Fact-vs–Fallacy-ejsr25

https://anchor.fm/walkinghomefromtheicu/episodes/Episode-32-Delirium-Day-ebe6po

-

Patients with delirium are:

- Less likely to discharge from ICU (Klouwenburg, 2014)

- 2x as likely to die during admission (Salluh, 2015)

- 3x as likely to die within 6 months after discharge (Ely, 2004)

- More likely to die 1 year after discharge (Pisani, 2009)

With each day of delirium there is a 10% increase in risk of death (Ely, 2004)

Delirium also causes:

Increased length of stay

- At least 1 more day in hospital (Salluh, 2015)

Increased time on the ventilator (Arumugan, 2017)

Increase risk of workplace violence (Jakobsson,2020)

Increased risk of line and tube removals (Tilouche, 2018)

Increased hospitalization and costs

- 39% higher ICU costs (Milbrandt, 2004)

-

- Ambulation at night improves sleep and decreases delirium (Nydal, 2021)

- Family presence improves outcomes for patients with delirium (Mckenzie, 2020)

- Family knowledge about patient may be beneficial in delirium management (Pandhal, 2021)

- Extended visitation policy reduces risk for ICU delirium (Rosa, 2017), (Schwanda, 2018), (Westphal, 2018)

- Avoiding sedation, improving sleep, and early mobility help prevent and manage delirium (Brummel, 2013)

- ABCDEF Bundle (ICU, 2021)

Family decreases odds of delirium by 88%.

Mobility decreases odds of delirium by 95%

(Bersaneti, 2022)

-

References:

Arumugan, S., et al. (2017). Delirium in the intensive care unit. Journal of Emergency Trauma Shock, 10(1).

Bersaneti, M., & Whitaker, I. (2022). Association between nonpharmacological interventions and delirium in intensive care unit. Nursing Critical Care.

Brummel, N., & Girard, T. (2013). Preventing delirium in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Clinician, 29(1).

Ely, W., et al. (2004). Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. Journal of American Medicine Association, 291(14).

The Face of Workplace Violence: Experiences of Healthcare Professionals in Surgical Hospital Wards

ICU Liberation Bundle (2021). Society of Critical Care Medicine.

Jakobsson, J., Axelsson, M., & Ormon, K. (2020). The face of workplace violence: experiences of healthcare professionals in surgical hospital wards. Nursing Research and Practice.

Klouwenburg, P., et al.(2014). The attributable mortality of delirium in critically ill patients: prospective cohort study. British Medical Journal, 349.

Marra, A., Ely, W., Pandharipande, P., & Patel, M. (2018). The ABCDEF Bundle in Critical Care. Critical Care Clinician, 33(2).

McKenzie, J., & Joy, A. (2020). Family intervention improves outcomes for patients with delirium: systemic review and meta-analysis. Australas Journal of Ageing, 39(1).

Milbrandt E.B., Deppen S., Harrison P.L. (2004) Costs associated with delirium in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 32(4):955–962.

Nydahl, et al. (2021) Mobilization in the evening to prevent delirium: a pilot randomized trial. Nurse Critical Care.

Pandhal, J., & Wardt, V. (2021). Exploring perceptions regarding family-based delirium management in the intensive care unit. Journal of Intensive Care Society.

Pisani, M., et al. (2009). Days of delirium are associated with 1-year mortality in an older intensive care unit population.American Journal Respiratory Critical Care Medicine, 180(11).

Rosa, et al. (2017). Effectiveness and safety of an extended icu visitation model for delirium prevention: a before and after study. Critical Care Medicine, 45(10).

Salluh, J., et al. (2015). Outcome of delirium in critically ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal, 350.

Schwanda, M., Gruber, R. (2018). Extended visitation policy may lower risk for delirium in the intensive care unit. Evidence Based Nursing, 21.

Tilouche, N., et al. (2018). Delirium in the intensive care unit: incidence, risk factors, and impact on outcome. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine, 22(3).

Westphal GA, Moerschberger MS, Vollmann DD, et al. (2018). Effect of a 24-h extended visiting policy on delirium in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Medicine, 44(968-70). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29605880/

-

Other resources:

Video on delirium: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FpAKs1ZWH04

Surviving delirium: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g50VsYj90zM

SUBSCRIBE TO THE PODCAST