SUBSCRIBE TO THE PODCAST

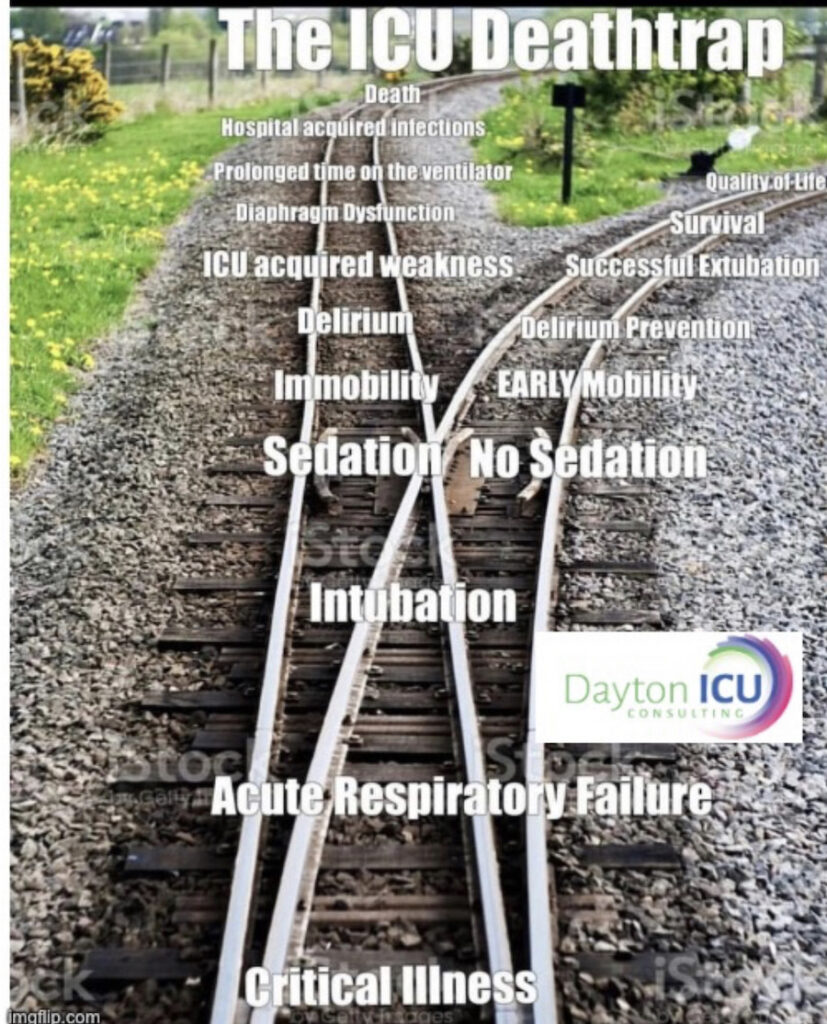

Why are prolonged sedation and immobility lethal? How do our standard practices of automatically sedating every patient on a ventilator deprive them of the chance to survive and thrive? What systemic barriers stop us from implementing evidence-based practices that save lives and drastically change outcomes? Michelle, DNP, ACNP dives deep into powerful case studies that explore the “ICU deathtrap”.

Episode Transcription

Kali Dayton 0:37

Okay, last episode we heard from Dr. Pittman, that the mortality rate in the awakened walking COVID-19 ICU is less than half of the other multiple COVID-19 ICUs in the same hospital system in the same community. Why is that? How does avoiding sedation and walking on the ventilator so powerfully impact outcomes like survival? To answer that, we must first see the reality of our current sedation and immobility practices, we must understand the legal repercussions of each step of standard ICU care.

Let me again clarify that the fault of these practices do not lie with one person, one discipline or one hospital system. This is a deeply rooted problem that has lasted for decades. Yet, we have to address it, we cannot fix what we will not confront. So please understand that in the case that is used, no one intentionally caused harm to patients. This is the product of a culture, habits, and an overall healthcare system that has created the ICU death trap.

Today we have Michelle Duncan with us, I am so excited because Michelle and I, we go way, way back. So this is really exciting for me. And I get to introduce her she’s been a nurse for 15 years, six of those years, was in the awake and walking ICU, and then she became an acute care nurse practitioner. She’s been working as a hospitalist and had accumulated a ton of PTO and wanted to help the COVID crisis and take a little venture.

So she took a contract as an RN in another state. And that was her first experience outside of the wake and walk in ICU and that kind of culture as far as critical care. And so we’re going to talk today about what that was like, Michelle, thanks for coming on.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 2:40

Thank you so much for having me. Kaylee, I’m so grateful.

Kali Dayton 2:43

So let’s rewind, share with us what it was like to work in an “Awake and Walking ICU”.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 2:52

Thank you. So I’m just grateful for the opportunity to kind of talk about my experience. So in the time when I was working as a nurse in the ICU, every day you get, of course report, you would walk every patient three times a day. I mean, patients, a lot of them were on high peep amounts 20 of people 100% And very sick, like people on chemotherapy people that were bone marrow patients, very sick patients, ARDS patients, you know, a lot of various things. But what it looks like is we walked every one every day, and we’d have the opportunity to connect with them. They were totally unsedated, they were able to walk and be human. And there was a lot of human connection.

A couple of things that I want to talk about were some moments where I connected with certain patients in that population. Is that okay? Specific, many times when people would get close to death or be really sick, we would bring them to the helicopter pad when there of course, wasn’t helicopters, or we would transport them or have them walk with us even intubated with ventilator or bagging them.

You know, outside the hospital and outside in nature after they had been in the hospital for so many days in the ICU for so many days. Also showering patients in the ICU daily, we showered every patient in the shower. Of course, you just extended your ventilator and you would shower them every night.

That was really interesting. These are something that connects to your body and your brain when you shower a patient. Also, some of the things I wanted to talk about is specifically one patient that I had. He had he was in his like late 30s He had had ARDS due to ALL and then chemotherapy than a bone marrow transplant.

And he had become so delirious because of all the things that he procedures that he had had done. He was on the ventilator for multiple days. He was on a PPL 20 and 100% for weeks. And he was so delirious and I remember specifically this patient. He was young, and he had multiple kids, and really just had a sense of we can’t let this guy day we just cannot let this guy die. And it was so tragic. But we walked him around the ICU. And so what that looks like, do you want me to explain a little bit what that looks like?

Kali Dayton 5:34

Yeah.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 5:37

So that looks like a team effort, for sure, you’re going to have multiple physical therapy, you’d have one physical therapist, you can have one or two nurses, you’re going to safely walk patients around the ICU. And so we would walk patients around the ICU. And specifically with him. At first, it was just a task to even get him to dangle at the side of the bed, and then step to the door. And then finally getting this guy to get strong enough to walk in the ICU multiple times a day. But his delirium didn’t get better.

He was completely delirious. And it was very interesting, because for multiple days, he, for weeks, really, he had been very delirious. And what we did was, his family kept saying, Oh, my gosh, he loves coke. He lovesCoca Cola, and it was literally one of his favorite drinks. It was really the one thing in his life that he brought them a lot of joy. And so they kind of said, “Do you think we could get some coke Chapstick and put it on his lips?”, because he was sitting up in the chair between his walks.

I mean, we hadn’t restrained and the chair was sitting up. And we really need him, his family would be sitting with them. And in one day, we it kind of dawned on me that like I lean his mouth out so many times a day, that I just put a dip of coke in I mean, one of the sponges into a cup of coke, right? Yeah, just said, just a Diet Coke. And just to let his lips touch it almost.

And there was something that happened in his brain, he reconnected to his brain in his body. And I’m not joking over the next few days, when I would put a little bit on his lips, and he would taste the sensation of coke, he would of course, not drink it or anything like that. And then I cleaned his mouth out afterwards, doing a complete URL cleanse. But there was something that connected is bringing his body. And that’s what I want to talk to talk about today is like a human connection, how we can take these patients and I see care is such such an art.

And I want to really talk about the connection between patients and us. And what that looks like. It’s kind of interesting, because a few months later, I mean, I’m just getting on my shift for work, and I’m in the elevator and there’s a guy in there. I totally have no clue who this man is. I have no clue who this man is. He’s not recognizable. And he turns to me, he said, “You, you!” and he starts clicking at me. And he’s like, “You’re the coke girl!” And I said, “The coke girl?” And I remember specifically thinking, “Oh, coke!”

And then I looked at this guy. And he had gained, you know, multiple pounds. He had hair again. I mean, he wasn’t kept sick. I mean, he wasn’t on a ventilator. He was the patient that I had had about three months before. And he said, I’m getting ready to run a 5k in a couple of weeks. And he’s like, I can’t believe it. And he had he had arts I mean, this guy was so sick, he’s three months out, he’s almost ready for his next 5k He was he was just doing great. And I thought to myself, it’s so worth it. Like the things that we do make such a difference.

The the things that we do on a daily basis, make a difference for patients lives. And there’s so long that all of us have kind of said this is definitely gonna die his cancer even if we get him through this ARDS, she’s gonna die. But I think just the prolonged hospitalization, the prolonged delirium, the prolonged intubation, that happened, but during the time, we didn’t let him deteriorate, we didn’t let him do poorly. Instead, we did our part to make sure he was safe and make sure he didn’t lose his function. And I don’t know what it was with the code was something connected. There was something that reconnected his body in his brain, and he lived to be resuscitated him with Coca Cola.

Kali Dayton 9:42

I was with you during that time, during that era. And we were just constantly told that “mobility is a life saving intervention”. And I remember you know, as a new nurse NPs would go in if a patient wasn’t willing to mobilize if they were refusing to walk which sometimes would happen. They’ll go in and have this heart to heart with them and say, “really? What what are you wanting to get out of this?” Refusing mobilitie was like refusing an antibiotic.

That if you do not want to mobilize, what are your goals of care? What do you want to do from now on, because we’re not going to make you be on a ventilator, we’re not going to make you do things. So if you don’t want to survive, then you’re welcome to stay in bed, but we’re gonna really have to change your your treatment plan. I mean, they were that hardcore about it, but it’s true mobility is life saving intervention. And that’s just the way it was accepted is accepted there.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 10:38

Yeah, and I needed to say that for a moment. I’m so honored by the NPS and MDs. And like all the people, all the physical therapists and the nurses aides and the nurses that taught me the art, that it’s so connected care, it’s such a care that is so connecting, and so compassionate. But it really does is the difference between saving people and not letting them live? It’s tragic, but it’s, it’s I’ve thought a lot about this in the last few weeks as we’ve been preparing for this, you know, interview.

And I thought a lot about what Dr. Gottman Dr. John Gottman, he talks about, he’s a marriage counselor. So this is like kind of not in our realm of ICU stuff. But he talks a lot about “sliding door moments”. And he or he always references a movie in 1988 called in 1998, called sliding doors with Gwyneth Paltrow. And it’s interesting because you see this woman woman who has to alternate lives, because she there misses her trainer, she gets on a train. And it’s it seems like a inconsequential moment or event and incident that affects this patient, this this lady’s outcome.

And it that’s what mobility and that’s what this type of care is, like, it’s moments that we sometimes think are not important, but really are. And they really are the determining factor of what makes your patient do better, or makes your patient do worse. And so my ask would be that we are more mindful those moments, and we really don’t miss out on the tasks, we’re not just so busy doing tasks, trying to check off our meds, trying to check off our things that we have to do with our charting that we have to do specifically a certain thing, right, that we are able to connect and see the the bigger picture, right?

So that’s kind of what it looked like in the ICU. We were mobilizing people, it was very clear when patients were gonna do poorly, because they were kind of getting pushed to either do better or do worse, very quick in their hospitalization.

Kali Dayton 12:59

Right. And you knew if they, I mean, mobility is just such a gauge, you could tell if they were, how their morale was doing, how their mentality was doing. But also how they were their cardiopulmonary function was doing by how they were mobilizing physical therapy would come to me as a nurse practitioner, and tell me how patients were doing. And it just gave me so much insight into their status, whereas they’re laying there, you have the same settings on almost every patient, and you don’t know what they’re doing. So yeah, I now appreciate that culture in that practice.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 13:33

And I want to talk a little bit about like safety of that. So in my career, I’ve had one patient self extubate. And I mean, you can imagine for all these years, we mobilize these patients, we walked him every day, every single day, every single patient. And these pictures are three or four pressors stations are on high amounts of people ventilated, very sick, delirious. You know, these are very sick patients. And so it’s not just saying, oh, yeah, we’re gonna we’re gonna emulate the people that are ready to be discharged from ICU that are now just on and these can.

These are not the people that were ambulating we are ambulating- it was the sickest of the sick patients. And it’s safe. I mean, in my whole career, I had one patient that did self-extubate and he gummed out his ET tube. And then I also had one patient that had was, I guess we would call it a “fall”. Only one in my whole career, and she actually sat down, she was upset that she had to walk so far. So she was assisted to the ground.

Kali Dayton 14:40

I really wouldn’t call that a “fall”. I would call that a “pout”. I would call that a “trantrum”. Being on the floor doesn’t really mean that they fell, but But yeah, that is such a rare occurrence that there is a fall during ambulation.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 14:58

No, and that’s the the thing is, there’s a big fear. That’s one thing that I learned. And as we talk, that’s one thing that I’ve learned. So, yeah, I did take this travel contract. And let’s kind of chat about some different points.

Kali Dayton 15:12

Yeah. What was that, like?

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 15:15

It was kind of traumatic. The burnout from the nurses was immense. I mean, the nurses were trying so hard. Everyone was trying so much, but it’s so hard, because that is the breeding ground for burnout. An ICU where patients are sedated, there’s no human connection. There’s no vulnerability, there’s no conversation, there’s no family members to connect to. I believe that a patient becomes a “thing” , or a “task”, instead of a human.

And that is because you are unable to connect with that person, if they’re just a room, like a 56 year old female in room three, or three, or, you know, this happens all the time. But instead of thinking of the patients as things we have to go back to like really treating them as humans. And that’s so much easier. That’s one thing that was so interesting to me.

It’s so much easier when they’re awake and talking to you. They’re not talking to you, when they’re lip reading, when they’re mouthing words to you. Or they’re they’re trying to get your attention, or they’re writing on their a pad of paper to you. It’s so much easier to have a human that you’re connecting with that you’re taking care of versus when you have a patient that is sedated and unresponsive, and you’re just turning, and you’re just bathing, but they’re not. There’s no input from that. There’s something that heals you and you heal them as you have a patient that’s awake and alert compared to being completely sedated.

Kali Dayton 16:46

Yeah, that is so profound. About 10 episodes ago, we did an episode on burnout. And Liz shared with us how she had never seen a patient BX debated. She started her career in the ICU right at the beginning of COVID. And hit for 18 months never saw a patient be extubated, and never really talked to a patient communicated with and connected with the patient.

And she didn’t realize how much weight on her until she transferred. Or she floated to begin shock trauma unit and had two patients excavated during that shift. And by the second one, she was sobbing in the patient’s room, when it all hit her just the joy, the relief, the connection that she felt hearing a patient’s voice.

And she realized that she had not heard that that she had lost her own humanity and her why for being in critical care because of the practices during COVID of deep sedation and immobility. And so what was that like for you, after you’ve seen patients mobilize? Basically the same kind of patients you treat in the past, but now you’re treating them totally different? You’re an RN, right? You’re used to being a nurse practitioner, kind of making the orders and here you are, in a totally different position seems completely different care. And you understand what’s going on? What was that like for you?

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 18:09

It was pretty traumatic, to be really honest, the the staff didn’t, a lot of them were so unaware, it was it was mainly a lot of lack of knowledge. They had never seen a patient awake and walking. So to even explain to someone what that looked like, was such a foreign contract concept for them. And so there’s a few things that are interesting.

But you want to think about is one of the burnout. Of course, too. It’s so quiet in in the ICU in the sense of like you just hear beeps, but you, you hear code blues happen. And you know, codes happen a lot, because people are deteriorating, and people aren’t recognizing it in. So that was something that was so apparent is, you know, when someone’s awake and alert, that they’re deteriorating in front of your eyes, and it’s so much more apparent than when people are sedated, and unresponsive. I had never seen so many bed sores in my whole career.

I think that we’ll talk about that a little bit later. Almost every patient had a bed sore every every patient was immobilized and sedated. It was a very big culture to have them sedated because they didn’t know any better. And they were so fearful. They hadn’t seen it. And so how can you expect someone who hadn’t seen it to practice differently?

Especially, it’s a call it was a cultural change. Even the doctors were fearful they could not believe that someone could be unsedated they unresponsive alert. And there was a huge fear around restraints. That was very interesting to me. There had been some improper uses of restraints in that facility. And no it was not okay to have a patient on restraints. So I think just there was some arrogance of doctors it was very much a culture of hierarchy.

Where it wasn’t okay to talk about certain things or to ask about things, there was never the words evidence base ever spoken by anyone in a facility which was very, very foreign to and very foreign. Because, again, in the ICU where we grew up, there was the most evidence based practice being treated, taught being treated. When there was a question, we went back to the evidence, we went back to what was best for the patient, what is what is the protocols? What are what are the best read? Or

Kali Dayton 20:38

Or what does the literature say?

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 20:41

Exactly. And so it was very different.

Kali Dayton 20:45

Wow.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 20:47

So it was hard.

Kali Dayton 20:47

I mean, because I, we talked on the phone, I’d say, “Well show them this study, or, or maybe approach it this way, or, you know, propose this”- and constant shutdowns.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 20:59

Oh, I loved that. So rounding wasn’t consistent and the doctors were so overwhelmed. And I’ve given them that because they had to ICUs that were 30 patients. I mean, they’re very, they’re so busy, that they would kind of just come and just try to clean up just the minimum of the issues. And they would come in, and then you would try to have a conversation like, according to the Society of Critical Care, medicine, they recommend that we could decrease some of the sedation or, you know, different things like that.

Yeah. And one day, I specifically remember the doctor who said to me, and I quote, “I don’t have time to talk to you about this, I have real patients to take care of.”– all those patients died. Every single patient died. In the time that I was there for eight weeks, I saw a total of five patients live. Most of them are patients that I had taken care of most of the hospitalization.

But it was interesting, because that’s total of all the patients in the ICU. So there was 25 beds. So if I bet you five survived five patients live. And so three of them had been trached. Well, no… Two of them had been trached, Two had been sent to LTACH, two went to the floor, and we’re on the floor for quite a long time because of deconditioning and immobilization. And then one made it home that I know to my knowledge.

Kali Dayton 22:28

So much. No, and the previous episode, we heard from Dr. Pittman, that at our home ICU, their survival rate is substantially different than the national average, but also within the same hospital system. Their mortality rate is less than half of the other COVID ICUs within that same system. So when we’re talking about these practices, people are like, that sounds nice, “froo-froo care”, but “this isn’t a hotel, we just got to get them to serve to survive. That’s all we can focus on”.—– But if that’s all we’re focusing on, that’s what we’re gonna do. We’re gonna keep them awake and moving so that they survive. But unfortunately, that’s not the way they see it. That’s not the way your team there was seen it. And that must have been really hard for you.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 23:16

Yeah, it was difficult, very difficult.

Kali Dayton 23:20

So let’s talk about a specific case study and break it down, step by step and plug in the research. Tell us about our prime example.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 23:31

Okay, so I want to talk we’ll call her Sally. I want to talk about a female. She’s 66 years old. We’ll call her Sally for the case study. Hey, so she was unvaccinated admitted for COVID-19. She had the classic cocktail of things. Coronary artery disease, hypertension, obesity, morbid obesity. times at home, they had reported that she got a little forgetful, but lived alone had two children also had six grandkids. I mean, and she function on her own, lived on her own was able to do all of her cares of daily living at home. She was admitted to the hospital on day 14.

For 14 days, she was on the floor. And we didn’t really know her nutritional status on the floor, but she was eating independently had been on six liters most of the floor say and she hopefully was eating enough to meet her metabolic needs. But then was transferred to the ICU because of oxygen demand, really. And then…

Kali Dayton 24:37

She was bed rest on the floor, Right?

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 24:39

That was one thing that was very specific. In this facility. It was very interesting. There was one one physical therapist for the whole hospital and she had a physical therapy aide on most days.

But the first few days Oh man, the first few days of my time at this hospital I was calling every day I was like, “where’s the physical therapist?”. And I was so used to having a dedicated physical therapist that would come and you work with every single patient multiple times in the day in the ICU. And so it was interesting, because after a few days of me calling and calling in them not coming, finally they came up and I said, “What’s going on here? There are physical therapy orders in, what is happening?”

And so it was kind of interesting, because one day, the physical therapist just turns, she just, she just looked at me, this poor, floor physical therapist, and she had a paper, a stack of papers, there’s five papers, and she just flipped, one to another just flipped 1,2,3,4,5. And each page had at least 20 to 25 patients. And she said, “I’m so sorry, I can’t spend 40 minutes on an ICU patient, because I have these five pages of patients that I need to see. And I haven’t seen most of them.”

And I thought to myself, “What a tragic story. This is a system problem. This is not this physical therapist not doing a good job or not caring, this physical therapist wanted to help so much. But this is a system problem.” That is really the issue.

Kali Dayton 26:12

Well, it’s a thorn in my side, I just, I don’t understand the rationale from the system, because physical therapists help save health care costs. They study after study, and I keep on promising this episode, the financial benefits, and it’s coming, I promise.

But we know that the more pieces mobilize, the shorter the phase will be, the less complications they’ll have, the more likely they are to survive, the more likely they are to discharge home. All of these things save money. So if we say we don’t have the financial resources to hire more physical therapists, that is a very ignorant decision making. So that drives me crazy. And then the fact that she was on strict bed rest for 14 days, blows my mind.

I think back to my own experiences with you know, having the flu, or I’ve punctured my femoral artery and have been in bed for a week. And when you get up even as a young, healthy person without this inflammatory process, like COVID going on, you’re weak. If you’ve been laying in bed, mostly supine, then when you get up after a few days, try to go up the stairs, you fell short of breath, you felt lightheaded, you do not feel normal, like yourself. And yet here we have high risk person with a hyper inflammatory response going on or process going on.

As she was taking her eating her own food, on six liters, I’m gonna get used to tachyneic, tired, these people are lethargic, they’re kind of mentally checked out. I doubt she was eating enough to meet her basic metabolic needs, especially to her baseline needs.

But we don’t look at that. We’re like, “Oh, they’re they’re eating, they’re probably fine.” But yet we’ve heard from dietitians, in these past episodes, how lethal that alone is become malnourished during that process. So you probably have some malnutrition going on. bed rest, which isn’t full in mobility, but bed rest alone is enough to cause someone to atrophy to the point of needing to be intubated. So we’re setting up this process to make people require mechanical ventilation. We’re exacerbating this inflammatory response, as the muscles break down.

That fuels inflammatory response. So that has to make COVID pneumonia even worse. So she was put into this process of care that basically said, “If it looks like you’re really sick, you could get worse, let’s just pour some gasoline on that process and get you into the ICU ASAP”. So that’s basically what happened, right?

I also want to mention, obviously, with COVID pneumonia, they’re at risk of about developing ARDS. And for some reason, we’re not talking about this certain study, I think it was in 2016. They took a group of mice put them into two groups, they gave both of the groups polyliposaccharides, to induce a lung injury.

And in the control group, they had them on bedrest, because that’s what we do. But in the event intervention group, they had them doing moderate exercise. And they found that exercise in the intervention group prevented atrophy in the limbs and respiratory muscles of those mice. And that exercise also to decrease the number of neutrophils and the ocular space. So we have to remember that.

Again, like I said, muscular atrophy in sites and feels inflammatory response, so when the mice had less muscular atrophy, their systemic neutrophil chemokine responses were regulated, and they had less inflammatory markers such as the granulocyte colony stimulating factor that gcsf in their plasma. And so that same drop in gcsf has also been seen in humans that receive early mobility during acute respiratory failure.

So when it comes to ARDS, yes, we have to remember that it’s the neutrophils and their mediators that caused the alveolar tissue damage, which leads to lung epithelial and endothelial injury. And that’s what causes the rush of protein rich alveolar edema into this, and then causes his whole ARDS storm.

So really, when she was admitted to the hospital, even on the floor, with COVID, pneumonia, this high risk situation, it should have been of high priority to mobilize her and nourish her and make sure that she didn’t atrophy and get set up to end up in the ICU. And yet, unfortunately, that’s what happened. And that’s what’s been happening in our COVID patients. As a standard as a norm. You’re sick stay in bed, you you’re safe to swallow, then you’re probably getting enough food. Check check.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 31:03

Yeah, and I will say, as a hospitalist, the more aggressive that I’ve been. I mean, I’m putting patients on the floor on 15 liters nasal Cannula working with the nurses and the nurses aides in our facilities have become much more comfortable with walking them, hyper oxygenating them and just walking them so many times a day. And that has been a huge determining factor when I transfer patients to the ICU or not. If they’ve been doing their proning and ambulating. It’s it’s a huge deal. If you keep them safe prior to being transferred, or prior to them deteriorating, if you keep them strong. I mean, they just do so much better they are able to be discharged.

Kali Dayton 31:45

I wish we do we would do a study. I mean, not that there gonna be a lot of medical floors. There won’t be, of course doing that practice. But if we could compare the acute care of patients that you’ve taken care of in the medical floor, with COVID compared to a control group, even within the same system and compare your ICU admission rates, that would be really interesting. Okay, so after two weeks of sitting there atrophying withering away in bed, she was of course admitted to the ICU, right?

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 32:16

Yep. And she wasn’t immediate, immediately intubated- that was her reason for coming to the ICU. And, again, culturally, in that facility, when you were intubated, you were sedated, and you were sedated and intubated. There was no…. there was no way that these patients were ever even started off with light sedation. I mean, it was very common practice that most of these patients in a general in general, so it was a very much a cocktail that happened all the time. Almost every patient we’re between would be on propofol between 30 to 65 mcg, and then, and then dexmedetatomidine around 14, and then the patient would be their max dose of fentanyl was 250 that continuous 200 mcgs continuous.

But again, that’s so much so, so many medications to sedate someone. I mean, most patients in that facility, were just laying in bed with a RASS of negative five. I mean, these were not not even going to flinch pain. These patients were not going to flinch. They were completely sedated and immobile. And there was really no need to paralyze these patients because they’re in such a deep sedation.

Kali Dayton 33:38

Oh, that’s crazy. So she’s on….

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 33:41

Specifically with her, she gets to the ICU. So it’s day 14 of her hospitalization. She gets intubated. They quickly started on clinimax, vasopressin, levophed, propofol, dexmedatomidine, and fentanyl but specifically her settings. So it’s kind of interesting, because at this time, I’m a nurse, and I’m watching her but I’m not her nurse.

So I would go in the room at times to reposition her or help other nurses. But I had other patients that I was managing. And so I would see her though and her room was always dark. And it was in kind of in a part of the hallway that no one turn on the lights. And it was dark during the day during the night.

I want to talk a little bit about that but basic nursing, of just turning on the light so patients don’t become delirious. Turn on the lights during the day, turning on the noises during the day, setting off the lights during the night shutting off the noises during the night and trying to you know decrease ICU delirium as much as you can. None of that happened and so almost like this room just stayed quiet for weeks, weeks, literally weeks. So for 42 days, I watched her room be completely dark, where she was sedated and unresponsive.

There were no family members, that was so tragic to me. This facility was not allowing visitors unless people were completely essentially going to die. They would allow one person to the hospital and they were so strict on that policy, which was very foreign to me because the the facility that I had come from, I mean, there is a risk of COVID. But again, if we can go in and wear PPE, you can train a family member to come in and talk to their family and wear PPE and be safe also.

So I finally get her as a nurse, it’s day 42. And, and I finally get my chance to be with her. So here’s Sally. And the first day that I see her. She’s on the clinimax, She’s on vasopressin. 0.02 units per minute, levophed 10 mgs per minute. Protocol 65, Dexmedatomidine 14, fentanyl 200. mcgs per hour. So let’s kind of talk about those. Those medications.

Kali Dayton 36:10

Yeah. And the clinimacs. I mean, not that it’s it’s bad. But I mean, she’s 42 days in. Why was she on clinimacs? Why not enteral nutrition?

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 36:20

Good. Typically, at that point, you could have put her on tube feeds and put it in like a, you know, a feeding tube easily. And that is always ideal is putting in a feeding tube letting their belly get fed? I think because of the chronic use of the narcotics, she had developed an ileus that have resolved, and then again, did poorly. So…

Kali Dayton 36:46

that makes sense. Because I know that we also hesitate to use a lot of enteral nutrition when we have vasopressors going. Let’s talk about that. I mean, so propofol of 65 an hour. I mean..

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 37:01

that’s, yeah, let’s talk about 65 an hour. What does that look like? That’s one to one, meaning that every hour, so you have 100 mils in a bottle. And that means every hour, two hour and 20 minutes, you’re changing that bottle. So as a nurse all day- you’re going and getting a bottle of propofol and you’re hanging at the time demand on that task alone. It takes away your time.

So if you think about all these drips that you’re just trying to not have them run out. So you’re running from accudose to accudose, making sure that you change it to mean on the protocol and you know, making sure that all your PPE every time you go in the room just for that one task of hanging propofol.

Kali Dayton 37:48

…… that is probably not necessary. Yes. Let alone a max dose should be 50.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 37:55

Yeah,

Kali Dayton 37:55

Why was she on 65? And why was that normal? In that?

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 37:59

That’s just what they did. And there wasn’t, again, as we question it…. as I questioned it, when I asked the doctors, “Hey, can we reduce this?” There was no talking to them about there was just it was just a culture. Like you didn’t question the doctors. And that’s that alone is toxic.

We could have a few podcasts on that… but how unhealthy that culture is. It’s not it’s not a safety culture, that that’s not a safe place.

Kali Dayton 38:25

So clearly titrating sedation was not up to the nurses. It was not evidence based. Clearly the ABCDEF bundle was not part of the discussion- which is crazy that that should be the standard of care. Yeah, so with propofol alone, I’ve shared extensively on this podcast the effects of propofol and episodes like at 64,65,66. So if you want to dive deep go back into that quick summary.

Propofol is myotoxic, it breaks down the muscle, which we just talked about how much that causes or can contribute to multi organ failure and impairs the sodium channels in the muscles and then our muscular connection is lost, so likely leading to critical illness polyneuropathy. Propofol alone is probably an independent contributor to diaphragmatic dysfunction.

So even even without mechanical ventilation, propofol alone can cause the diaphragm to be dysfunctional. It increases hyperglycemia, which increases the risk of it acquired weakness, it prevents sleep, which is probably one of the main reasons it causes delirium, which alone, delirium alone doubles the risk of mortality during that admission, so we’re essentially doubling their risk of death with propofol.

And obviously, at a rate like 65 mcg/kg/hr, and a RASS of negative five, they’ve impaired their her ability to mobilize and preserve function leading to ICU acquired weakness, which is you acquired weakness, which we’ll get into the mortality rates, but that alone can make them eight times more likely to die.

and then dexmedatomidine, I’m just not sure why that is on in addition to a propofol, any thoughts?

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 40:06

Um, so a culture of “this is how we do it”- is what happened. And so, again, not being able to question that culture. And that’s tragic when that happens. That’s a very much a system problem.

Kali Dayton 40:22

So who started that? Who said, “Wow, they look like they’re really sedated on propofol. Let’s add in some dexmedatomidine.”- My only thought is, we do know that precedex, is less disruptive to the brain, and that the brain activity under dexmedetomidine more closely resembles sleep. It’s still not real sleep, but it looks the closest. And so in studies, it’ll say that, um, that it possibly prevents delirium, and has lower rates of delirium. So were they trying to use precedex to prevent delirium while giving propofol? That’s the only thing I can think of

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 40:57

I am not 100% Sure, on the rationale, it didn’t make sense to me. It didn’t wasn’t evidence based. And so again, when it was questioned, I mean, it’s really easy when you’re a nurse practitioner, because you just change the order and say, we’re not doing that. There’s a nurse, you can only write in the chart recommended to MD to change this order. And he refused. I mean, there’s nothing more part of that.

Kali Dayton 41:21

Yeah, a lot. Cover your backside, because this was my loved one in the ICU. And they were getting lethal treatment. This would be something to bring up in court.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 41:34

It’s ery interesting. Yeah, it’s very interesting, because the other thing is, when you do a RASS score, a RASS for me of a negative one or negative five is, there’s a lot of subjectivity of it, where you’re, you’re saying, “Oh, they’re RASS of negative two, they’re RASS of negative four you know, they’re a RASS of negative five.”

But it’s really, it’s really kind of a gray area in nursing. And it’s tragic. Because it’s easy. It’s very,……it’s not easy, actually, it feels easy. It feels it’s not vulnerable, you don’t have to talk to anyone, you’re not going to talk to anyone, but you’re not going to have to help swab someone’s mouth out multiple times when it’s on their timetable.

It’s not harder care. When you ambulate a patient three times a day in they’re awake. It’s more gratifying care. But the one thing that we have to remember is, it is just as hard to have to run and give these drips and continuously be doing these drips and then turning dead weight. Turning patients that you need for people to move and mobilize them because because they’re in mobile, completely unresponsive because of a sedating them.

So you just have to say where are we going to put our efforts? And so that’s one of the things you really have to look at when you have buy-in. One: these nurses were so scared, they had never seen a patient up and awake on a ventilator. And there was that in conjunction with fear of restraints, and makes it very messy.

Kali Dayton 43:16

Yeah, it’s really complicated. That is such a cultural myth- that sedation makes things easier. But I’ll refer back to Episode 76. With Alex who’s also travel nurse, she really laid it out that it’s so much harder to create this whole mess, the storm of delirium, the atrophy, the death, I mean, and the run with the drips. Because in the “Awake and walking ICU” right now, with these COVID patients, they’re not on vasopressors .COVID does not cause hypotension, or any shock.

It really does not. What does cause hypotension is 65 of propofol. Dexmedetomidine can cause hypotension. So essentially, she was on norepinephrine and vasopressin because she was on propofol and dexmedetomidine. I do want to say with dexmedatomidine, that it’s not a bad drug. I mean, it just totally depends on how we use it.

It’s concerning that it was used for so long and you’re with her on day 42 That’s weeks of dexmedetomidine I’ve never seen it used that long. Back in episode 71, When I interviewed Megan Wakley, dexmedetomidine It was like the drug of choice onpoint for her because she was delirious when we tried to keep keep get her out of versed.

She was thrashing, she bit through her tube. I mean, it was dangerous situation. So we put on it’s an atomic thing to get her down to RASS of one or zero, so that we could mobilize her. You can mobilize someone when they’re trying to punch your face out right.

But that’s what facilitated mobility family and real sleep was dexmedetomidine In that moment, and then after we would mobilize her and she crashed out, she was so exhausted, and we turned off the precedex. So we just use that to bridge to being fully liberated from sedation.

But never have I seen it for a deeper RASS of less than zero, or for weeks. And we have to remember that it can cause this, this tachycardia and this this dangerous tech, tachyphylaxis that makes it really hard to wean off later, which is what I’m hearing from teams that I’m consulting with. As well as listeners – that they’re coming in, and patients have been on dexmedetomidine, for whatever reason for weeks, and now it’s a really dangerous, difficult process to manage their blood pressure and their heart rate when they try to wean it back. And so it’s just not necessary. Why was she on it?

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 45:47

Exactly.

Kali Dayton 45:48

And fentanyl, another question of why was she on it? Fentanyl is not a bad drug.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 45:52

Right.

Kali Dayton 45:53

But why? Why give it at high doses? When it causes ilieus, when it causes dependence? What did they ever assess her need for fentanyl? Was she in pain? Did she have air hunger or ventilator dyssynchrony? I mean, what was it just a….

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 46:08

Beautiful. Yes, that’s beautiful. And I want to speak to that. So day 42, I have her as my patient, I get report, I walk in the room, and I just hit stop on all of the meds. I mean, I, I know it was a little aggressive, but I was just kind of like, “why? She’s not even responsive.” And so essentially, we knit down within an hour and everything was off. And, and that was pretty aggressive. I guess people could say that was aggressive. But, you know, usually, within a few hours,

Kali Dayton 46:41

Some may say, if she’s been on it for that long, you don’t want to abruptly stop it. And yet, when they’ve been on it for that long, there’s probably an accumulation of that. So they’re not going to go into withdrawal.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 46:51

And that’s one thing that is a false belief. I really believe that because they would say we can’t reduce it very fast, but in reality that’s gonna stay in their body for such a long time. And plus, even just as tiny bit of narcotic will help decrease make it so you don’t withdraw. So five or 10 of oxycodone every six hours.

While you’re so why keep the fentanyl to sedating level, we just cover the withdrawal part. Right? Right. And so of course, you always keep in mind that you don’t want that patient to withdrawal. But clearly, I mean, we shut that off and within by 10 in the morning, so we started the shift at seven.

By 10 in the morning, the patient was completely off of all of all drips except for leave a Fed she still needed between two and four. vasopressin was off. But illegal federally went from 10 to two to four. That’s I mean, that’s huge differences. Her pressure was fine. She was awake, and she was just resting in bed. Physically, she was so fatigued, she couldn’t lift her arm, she was so atrophied.

Now I want to make a point to when I worked in ICU as a nurse, and the patients are awake and walking. One thing that we always do, if unless the patient on a rare occasion, we allow them to not be restrained. But we do want them to be safe. We don’t want them to be confused coming out of any type of delirium and rip those teams out.

And so we’ll lightly restrain them and we’ll reach we’ll talk to them, we’ll kind of coach them through those moments. We’ll say, “Hey, we’re putting these restraints on so that you can remember if you fall asleep or something and wake up that you saw that tubing, you can’t rip it out.” And that’s what makes people bit patient safe. And you’ll just say, “Are you okay that we have these restraints on you?” And I really people say “yes, yes, I’m fine.”

Kali Dayton 48:48

they asked for it. “No, I’m afraid that I’ll wake up…”, I would be afraid because I’m sleep-walker. So like, what if I pulled this in my sleep, “please put this on me, keep me safe. Because I know that morning. I can be awake, safe and free.”

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 49:04

Right. And that was something that was scary because this facility was so fearful of using physical restraints. They were not fearful of chemical restraints. But physically restraining them was such a taboo in this facility. That one thing that we did is she was so physically fatigued, she couldn’t lift her arms very much.

I had her try to write, but it was really an an understandable because she was so weak and her and had such bad muscle atrophy. But one thing that she could do is she could lift like she could lift words to me. And so we talked and I would say like say “yes or no. nod your head yes or no if I asked you a question”, so I’d ask her stuff like, “Do you want to talk to your family?” And she got so excited she started saying “yes!” And I said, “Let’s call them Do you want to call them on FaceTime on your phone?”- and she got so happy she was so excited because I reoriented.

Of course you wake them up, you reoriented me say, this is today they’ve been in a coma for for, you know, 42 days at this point. And so you want to bring them back to what what’s happened is since you last fell asleep. Well, you weren’t asleep since you last became sedated since you last got knocked out because of medication.

Kali Dayton 50:18

It’s also amazing that she was able to one, wake up, because that level of propofol for that long, especially with morbid obesity, I would have anticipated that she would have taken days two weeks even become responsive, let alone communicate. And it sounds like she didn’t have terrible delirium.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 50:38

So she was very confused on her situation, and on the date, and the time she she was forgetful of those things. But she knew who she was. She knew her daughter’s and she knew that she wanted to talk to her family. She had no recollection of what had happened, that she was talking about.

While she was sedated, or what kind of brought her to that point where she couldn’t move her arms, she couldn’t move her legs. She she did. She reported that she didn’t have she was very comfortable. She didn’t have much pain. She was very edematous. And she had such a bad bed sore at this point. I mean, she had a stage three coccyx bedsore. She also had much swelling and heel sores. And so….

Kali Dayton 51:23

It’s amazing that that I mean, we can really trace a lot, if not all of that back to this decision to give those medications. I’m just thinking about like fentanyl alone at a rate of 200 miles per hour….

we can do a lot of damage. And so she she couldn’t even get proper nutrition because of the ileus she had. Because of the fentanyl, it probably wasn’t even necessary. For every equivalent of 10 milligrams of morphine, there is a 2.4% increased risk of delirium, which probably isn’t telling very much right, but 200 milligrams per hour, that’s an equivalent of 50 milligrams of morphine per hour.

And three, that’s a total of 350 milligrams per day of morphine, which increases the risk of delirium by 86%, within 24 hours, but we’re not seeing that wave. And then because we’re giving those medications of fentanyl, that doesn’t mean that atomic the propofol, or it can mean vasopressors, which we know are not benign.

I mean, it’s a life saving drug during shock and when it’s actually essential. But when we’re doing that, just to compensate for propofol, we’re setting them up for increased vascular resistance increased afterload. And overall myocardial oxygen demand, increased pulmonary vascular resistance, and then arrhythmias, mesenteric ischemia, chest pain, coronary artery constriction, like vasopressor, vasopressin alone increases the risk of an MI. why did why do they need that on top of COVID.

And then we’re putting in central lines, because we’re giving vasopressors because we’re giving sedation, I think, in the wake and walk and Ico, they quoted, maybe about half of their intubated COVID patients have central lines. Whereas in any other ICU, you get intubated your Ottomans getting into central line, because you’re going to be on sedation, and you’re gonna need vasopressors. It makes me crazy.

And on top of it, I know I’m rambling, but vasopressors triple the risk of developing ICU acquired weakness. And again, ICU acquired weakness, makes you eight times more likely to die. So we are basically choosing their death by choosing these medications. And again, I know I’m preaching to the choir, but I get fired up about it.

These are not benign medications, just because we use them all the time does not mean that they don’t have consequences. So we really have to look at the big picture and triage their use and weigh the risk versus benefits. It’s like, if we get the medications, we’re designating them to die. Is that worth our convenience in that moment?

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 54:03

Exactly. And I totally agree with all the things you said it’s very good. I want to kind of mention what she looks like. On a lab standpoint, her renal function at this point was good. Her settings at 7am That morning were assist control peep of 10 and 60%.

And I know that we talked about a little bit about her foot she had significant but drop and that’s something I just want to put a plug in for. If you have a patient that’s immobilized, they need their feet propped up, or if you leave them in that position where they just caught it causes contractures so now she has bilateral foot drop, which is going to cause you to not be able to ambulate again

Kali Dayton 54:43

That’s, that’s a lifelong thing. That’s a big deal. That’s that causes a lot of suffering for a long time.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 54:51

Exactly. So, again, she was pretty excited about her conversation that she was going to have with her family. By the time I took off all those medications, she went down to a peep of seven, and 60%. But she was still on assist control. And so the respiratory therapist and meek said, “Hey, let’s do a spontaneous breathing trial, just try it on CPAP see how she does.”

Kali Dayton 55:20

…and you come in with this evidence based perspective. You go and you do this sedation vacation like and a real sedation vacation, not one where you just turn it down and have to see them thrash, and or the sedation back on, you really worked down the sedation, clearly more aggressively than most.

But you in a moment as a nurse chose to provide evidence based care. Andwe know in the evidence that deep sedation in the first 40 hours of an ICU stay, has been associated with delayed timed extubation, higher need for tracheostomy, increased risk of hospital and long term death. So you showed up to your shift wanting her to survive.

You were there to save lives. So that’s why you turned down and off the sedation. The ABCDEF bundle is the gold standard of care. Like sedation vacations should not be optional, should not depend on what nurses on ,what doctor’s on, what facility you’re in. Everyone should get the A to F bundle, which I think that means only start sedation when necessary. And if it is necessary, do sedation vacations.

I asked the listeners on the podcast if they thought that failing to if failing to practice ABCDEF bundles should be considered malpractice. And 72% said “yes”. So I just think that’s really an interesting inquiry. I’m not saying don’t, you know, run a bunch of lawsuits. But could this be considered malpractice in court? Could this risk our licenses, if we are giving lethal treatment to patients.

– Even if it’s a cultural norm, the evidence clearly shows that these are puts patients at much higher risk. For example, even with the pressure injury alone, that is an independent risk factor for mortality in the ICU. So just because everyone gets pressure ulcers doesn’t mean that has to be par for the course and that it’s okay. We are setting them up to die if we let them rot— literally Pressure injuries are rot.

Over half of patients that develop Pressure injuries will die within the following 12 months. So the aid of ethanol prevents that. And yet if we’re not practicing it, we’re not truly trying to save lives. So you go in, you should have the sedation, you change that outcome, that decision that day for that patient, you humanize her process. That’s amazing. It’s amazing that she was awake.

81% of ICU patients have delirium. So she clearly had some delirium, but it was far better than I would have expected. And then what’s your what’s your next step? I mean, you obviously wanted to get her moving?

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 58:01

At that time, she was on a peep of five, and 70%. But she was so honest, this control. Now she was looking really good. And we told her, we were gonna switch her over to CPAP and do a spontaneous breathing trial, see how she did. She became tachypneic during her spontaneous breathing trial, and she looked red in her face.

But we have to remind ourselves that we are bringing grandma on a marathon run. It’s literally after that many days, can you imagine not mobilizing that many days and then going for a run. That’s what we were doing. We were taking a woman who was not used the muscle function that she needed on her own, spontaneously on her own. And we were working it to the max. And so the next rotation would be yes, you will get flushed in the face, you will get tired, and you will get worn out a little bit.

And she did get worn out. So about 45 minutes into that. The respiratory therapist said, I really think we should switch her back to assess control. She didn’t look horrible. She actually looks pretty good. She just looked flushed, to be expected again. And then I kept my neck right, right to kip neck, and I recommended doing ABG and they said oh, I think we should just switch her back. And so we switched her back, which was fine. And, and she she was kind of worn out. And it was interesting because I went into a room and we called her family to do FaceTime. And she was so excited about that.

We FaceTimed, but they didn’t answer. So I kind of left the room. And then it was very interesting me as I got informed that we were going to swap patients. I heard and I started giving a report to the next nurse.

Kali Dayton 59:47

And I think we think that kind of scenario that that was a “failed breathing trial”. And in my mind, that’s not a failure. That’s part of rehabilitation. If you absolutely did the right thing and that’s been the should be part of the report to the next nurse, to the next respiratory therapist, to the next physician to say, “we did a breathing trial, she was able to sustain her own breath for 45 minutes”.

That should be done at least that long or that frequently the next day, and be exactly what that everyone should be focused on. What could she do today? What are we going to do tomorrow? How are we going to continue this process to re strengthen her, she was able to oxygenate on those settings, breathing on her own, that is a sign that it’s time to rehabilitate that it’s time to move on that it’s time to get work on getting extubated.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 1:00:35

That is a step in the right direction. And you as a nurse facilitator, that’s amazing. And one thing that’s interesting is she didn’t become hypoxic at all. I mean, yes, she became tachypneic a little bit. I mean, her, her respirations were in the 30s. But she did and she looked flushed, but she didn’t desaturate, so she was holding her own. It was good. So I give report to the next nurse. And he was on board he was so he was like yeah, she’s she’s looking really tired, though. And I said, Yes, she is. We just took her on a marathon run, you know, we just worked her so hard.

And it was really interesting, because I finished up report I said, “Can you make sure to call her family? I think this is really important. She’ll answer all your questions yes or no, just keep talking to her. Keep reorienting her. Let’s help her. Let’s keep these lights on. Let’s keep her in the best place possible.”

And I finished report with him and I go and get report for another patient. And this is my sliding door moment. I’ve walked back over and I see he has a bag of fentanyl, a huge bag of fentanyl. A container of propofol and another container of dexmedetomidine. I literally started running, started running over to him. And I started I said, “whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, what are you doing? And I was like, uh, Paul, I was like, What are you doing? I just gave you a patient that’s doing better.”

And he said, “she looks uncomfortable.” I said, “Yeah, remember how I just said that. We just took her for a marathon run. And she should be tired, we should let her have a little break. And we put her back on assist control. And we should let her rest for a little bit.” But I said “she’s telling us that she’s not in pain. She’s telling us that she’s okay. She’s telling us that she wants a doctor or family.”

And he said, :Well, she looks uncomfortable.” And at that point, I can’t persuade someone because I’m not the nurse practitioner. I’m working as a nurse that this isn’t correct practice. And I said, “Well, I’m like, just just just trust me just trust that this is going to work out if you just don’t sedate her.” And he said, you know, “We know her outcome. She’s gonna die just like all the other COVID patients.”

And I said, “Well, how can you say that she’s only on five and 60% She’s on assist control five and 60% when most of her her hospitalization, she was on a PEEP 18 and 100%.- I mean, she’s improving and she’s getting better. Her lungs are sounding great. He’s basically made it through COVID.”

Kali Dayton 1:03:08

I mean, the pneumonia is basically gone. Yeah, she’s made it through COVID.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 1:03:13

Right. And so it’s the sliding door moment. She gets re-sedated, and I don’t have her again for 14 days. And so again for 14 days, the lights are off. The room is quiet. There’s no visitors. There’s no FaceTime. And she continues to have bed sores. She continues to have foot drop. And it’s a mess.

Kali Dayton 1:03:34

Oh my gosh, that’s so that’s, that’s over 50 days. That’s like, that’s almost 70 days. Yes. That’s crazy. I’ve been deeply sedated and immobilized. That is gonna keep saying it. But that is lethal. I’m a healthy 32 year old you put me in deep sedation and and, and mobilize me for 70 days you’re gonna you’re going to kill me. Right?

That’s so traumatic. I mean, a peep of what? five and 70%. That’s just five or 40%. That doesn’t say “deathbed” to me. That says TIME TO HUSTLE- time to rehabilitate to get that tube out. Time to breathe, strengthen the diaphragm, the respiratory muscles so that you can breathe on your own and be free of this.

I just don’t get that the mentality that that…. that he was helping her “be more comfortable” via sedation is one of our big huge barriers in our critical care community. Sedation does not treat pain or anxiety. It masks it. And she didn’t have either. She was not in pain. She was not anxious. She was probably just exhausted from her marathon run her sprint for the day.

The treatment for that is rest in real sleep. REAL sleep. So the rest is beyond his control, having the support from a ventilator and then sleep is being off of sedation and actually sleeping because you’re tired. But that is not what we understand. And yet, and so in turn, they subjected her to more lethal treatments and torture.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 1:05:13

Right.

Kali Dayton 1:05:13

So then what happened after 14 days more?

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 1:05:17

So 14 days more of the first day I had, I didn’t have a student, but most days, I have either at least one student. So 14 days more that day, I have three students, I have two nursing students and one and one travel nurse that I’m training. And I love training. But that was definitely common almost all days, I was had at least one person, at least one student that I was training most days.

So next, so what happens is I finally have three nursing student, I mean three students, and I’m able to mobilize her we have a family, a family care for a family consults that day. And the doctor explains, you know, she needs to be tricked, she’s not getting off of the ventilator, we can’t get her off of the settings. But again, she needs to have sedation stopped.

So immediately, that day, again, we stop everything she’s now off of pressors completely. She’s off of everything, but the clinimacs Because everything got stopped again that morning, she wakes up, we have the family console, the family console goes okay, in the sense of the doctor says we can we can take this patient and trach her and let her go to rehab.

But there’s never a space in here, that it’s an option for this patient to strengthen now, and improve and get strong enough to be able to get off the ventilator. Because now she’s in a place that she’s so deteriorated, she’s unable to even raise her own arms. She’s been sedated for another 14 days, she has bed sores, and this is what we need to do. But that wasn’t given as an option. So she got the option of either being trached or being withdrawn on.

Kali Dayton 1:07:05

Was rehabilitation of the diaphragm, respiratory muscle strength…. was that was that ever discussed at the bedside? Did the doctor ever ever say to the nurse or say to the family, “she has diaphragm dysfunction or diaphragm paralysis, we need to strengthen the diaphragm a trach will help us do that”—– which the whole thing with the trach makes me crazy I’ve already discussed on the podcast.

Tracheostomy does not mean it’s safer, or easier to mobilize someone it might be more comfortable for the patient. I’ll give them that. But it doesn’t mean it’s necessary. In order to have a certification to turn off sedation or mobilize a patient it is safe and feasible to mobilize patients with endotracheal tubes.

It is just as safe to do that with an ET tube as with a tracheostomy that is a cultural myth that you cannot take off sedation and cannot mobilize a patient until their trach. So we’re letting patients lay them right and then say we can’t really rehabilitate them until they have a trach. That is not evidence based.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 1:08:02

Exactly. And so that’s what’s difficult is if you have a culture that won’t even let the person be awake when they’re intubated. There’s no area for them to ever live if they get in this situation. And so it’s tragic. So I kind of stepped in it during the family consolation, I said, “Let’s try to strengthen her a little bit. Let’s strengthen her.” So I knew that I had enough staff that day, I knew that there was going to be helpful physical therapy. And so I grabbed my nurses, nursing students, and we dangled her and I, in my career had dangled so many patients.

Every day, you’re tingling patients, and then you get them to stand and then you get them to walk and the strength that it took to lift a body that has been immobilized for that long. And then to try to help them just barely keep, I mean, just try to just kind of stay aloof for five to 10 minutes. We did it for 10 minutes, it was so much yes and keeping her head up. But she she did it twice that day. And this was interesting. I want to mention this.

The nursing students braided her hair, they washed her hair, they braided it, it was all matted of course, because of being immobilized for so many days. But they put it in double braids. And it was so interesting because again, I talked about that human connection. So we had two people help hold her and help her like work and we said keep keep keep your head up, keep your head up, keep lifting your head up. And she she worked with us.

She worked so hard. We had her hands on the side of the bed. We put our feet on the ground, and then the nurses wash your hair and and nurses students wash your hair and braided it. And it was so interesting because their satisfaction of how that shift went was so high. They were so happy. They left that unit and said “We made a difference for this patient. I know that this patient had such good care today.” And there’s just something so basic, but the patient became a human for them.

Kali Dayton 1:09:57

And they connected with that and they remembered why they were going to school, why they had signed up to be in this career in this specialty. Because they provided humized care and they felt even here you feel like you’re making a difference because you are and not just pumping meds into a flatbed body zombie.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 1:10:14

Right, exactly. So it’s kind of interesting. We had her one more day, we dangled her again. And then I left the facility. The day after they extubated her, even though she hadn’t been able to be strong enough, because the family had expressed they didn’t want her to be trached, but they didn’t want to continue if she couldn’t get help. And the facility was unwilling to keep her strengthening, because that wasn’t…..they didn’t have any systems set up to do that. And so 12 hours after she was extubated, she died.

Kali Dayton 1:10:53

So she had minimal ventilator settings. She probably could have passed, I mean, done CPAP for a little while. But doing CPAP. Picking your own spontaneous breaths completely independently, for a few hours is different than for a few days. She couldn’t even last 12 hours she couldn’t even ventilate, expand her lungs enough, moving of oxygen and air, and of gas exchange because of low tidal volumes, I’m sure, enough to survive.

That was not COVID. She did not die of COVID per se. She sounds like she died of ICU acquired weakness and diaphragm dysfunction.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 1:11:33

Yes, exactly.

Kali Dayton 1:11:34

Which, like I said, I’ll say for like the fourth time— ICU acquired weakness alone increases the risk of death by eight times. But let’s talk about diaphragm dysfunction. And I see acquired weakness with mortality. So a two year survival rate for all ICU survivors is 64%.

Survival rate for ICU for patients with out ICU acquired weakness, nor diaphragm dysfunction is 79%. So if you keep patients strong, physically strong, and with strong die of diaphragm, there, they have a study 79% chance of surviving the following two years.

And survivors that had ICU acquired weakness alone had a 46% survival rate. But those with ICU acquired weakness and diaphragm dysfunction, like your patient had a 36% survival rate. So when you keep them functional, they have a 79% survival rate. If you let them have terrible atrophy and set them up for failure.

They have a 36% survival rate and that’s with rehabilitation. But if you refuse to rehabilitate them, then they have probably clearly like a 0% chance of surviving if you never rehabilitate them, like that team did for her she had a perfect storm for ICU quiet and weakness, a diaphragm dysfunction, the immobility, mechanical ventilation, sedation vasopressors, altered nutritional status on top of an inflammatory disease process.

And she had the sign her signs of diaphragm dysfunction were probably low tidal volumes, high respiratory rate when she was on CPAP. And that’s just not sustainable for someone that’s been on ces control for 50 plus days without any mobility.

So ultimately, at that point with the people five, a failure to 40% respiratory failure and death in that moment, was not from COVID pneumonia, but from ICU, quad weakness and diaphragm dysfunction. And that was all probably preventable. Had she had evidence based, humane best practices implemented from the very beginning.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 1:13:45

Yeah, I absolutely. I just want all of the listeners to really feel this and really realize that what we do on a day to day basis makes such a difference. And if we can lean into the uncomfortableness of not knowing how a patient is going to do in the sense of like, it is harder, it is hard to have them sedated to have them awake.

Sometimes they can be annoying, because they’ll they’ll talk to you more, but you’re going to save your patients, you’re going to make them live. And if there’s one thing is just just get away from the culture, and if you’re doing stuff, just be here doing stuff, always question it, like ask yourself, why are we doing this? Is this safe? Is this best practice?

And none of the things that were happening were, I mean, most of the things that were happening were not correct. And so I invite people to do their best and to try hard to look at changes in our systems so that we can have patients live and it’s not because of us that they die.

Kali Dayton 1:14:58

And you as one nurse. It made a difference in her care in her day. Had you had her from the beginning had you had her consistently had, the team had more of a collaboration and were willing to be taught, discussing evidence, her outcomes who could have been so different? I mean, you can make a difference as a nurse. This all started because of Polly Bailey.

Back in the late 90s. It was one nurse that asked why, why not? Why are we doing this? Why are we not mobilizing them? Is there any reason looking into literature and she couldn’t find a reason not to mobilize them. And she found her own reasons to prevent harm. So she went for it. With the support of a physician, the Medical Director, Dr. Clemmer supported her, and doing something that made sense that was different than every what everyone else is doing different than what they had been trained to do.

But he understood this is an evolving field. And because of that, Polly Bailey has saved 1000s and 1000s of lives. And starting out as a nurse, she’s now a nurse practitioner. But as a nurse, she’s when I started, this new ICU, she was allowed to head, the ICU, hire the people train them, develop the practices of the protocols as a nurse. So I want nurses to understand how powerful they are, that you probably had more power in that moment over that one patient than even the physician did during that day.

Michelle Duncan, DNP, ACNP 1:16:23

Exactly. And when we look about when we look at the things that happen, it just really makes such a difference. And so don’t discount how important you are as a nurse as a physical therapist. And you can’t change it. Like a lot of the things that we talked about today were system problems that needed to be changed from a system level.

And it wasn’t any one specific that was trying to do bad because everyone goes into these situations, they want to give the best care, they want to do the best for their patients. But in reality, we have to ask ourselves, what are we doing. And so I just invite everyone in this podcast to really look at, look at what we’re doing, look at what our practices are, ease and roll it that a patient that can be awake can be alert, and it is a vulnerable place.

There’s risk there, you don’t have certainty that they’re not going to move, you don’t have certainly you don’t have complete control on how they breathe, or what they do. These are spontaneously doing it. But I would go back to what Brene Brown always talks about how being vulnerable is such a birthplace of happiness and such a birthplace of helping that burnout, helping that fatigue. And just the amount of fatigue that I saw, the amount of burnout that I saw, I just there’s a better way. And that’s really, what I hope we can get to is there’s a better way where we can compromise the way we live functional lines and go go around that 5k, three months after discharge, I think there’s a better way.

Kali Dayton 1:18:01

And again, none of this is to demonize anyone demoralize anyone. We’re so grateful for all the wonderful providers that have stuck through this pandemic and still given their heart and soul and to caring for patients and doing what they can. I hope that this message brings hope that the outcomes the process of care we’ve experienced throughout the last few years and even decades, is not what’s going to be happening in the future of Critical Care Medicine, the future of Critical Care Medicine will be a standardization of awaken walk in ICUs.

And I’m excited to be a part of that I’m excited for every clinician that’s listening to this podcast that’s trying to make the difference. All of these ICU evolutionists throughout the world are part of this, this change and are the pioneers of this. And that’s something to be proud of. So if things don’t change, day to night, over, over 24 hours within your unit. Even if you don’t radically have a patient walking out the ICU under your care tomorrow, you are making a difference hang in there. All of the research that I’ve referenced during this episode is found in the blog. And so you’re welcome to use that so that to your team.

Get that discussion going and share this with everyone you know, go to iTunes and leave a review helped make this podcast little more visible to the rest of the ICU community so that when you have these discussions, people have already heard it, heard the concepts, understand what you’re talking about, and the conversation can be more productive. Michelle, thank you so much for sharing your crazy ride and it’s all that you do. Hang in there.

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

References

Files, D. C., Liu, C., Pereyra, A., Wang, Z. M., Aggarwal, N. R., D’Alessio, F. R., Garibaldi, B. T., Mock, J. R., Singer, B. D., Feng, X., Yammani, R. R., Zhang, T., Lee, A. L., Philpott, S., Lussier, S., Purcell, L., Chou, J., Seeds, M., King, L. S., Morris, P. E., … Delbono, O. (2015). Therapeutic exercise attenuates neutrophilic lung injury and skeletal muscle wasting. Science translational medicine, 7(278), 278ra32. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3010283

Vasopressors contribute to ICU-associated weakness

Smith MD, Maani CV. Norepinephrine. [Updated 2022 May 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537259/

Episode 80: Big Picture of Propofol

VanValkinburgh D, Kerndt CC, Hashmi MF. Inotropes And Vasopressors. [Updated 2022 Apr 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482411/

Ahtiala, M. H., Kivimäki, R., Laitio, R., & Soppi, E. T. (2020). The Association Between Pressure Ulcer/Injury Development and Short-term Mortality in Critically Ill Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Wound management & prevention, 66(2), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.25270/wmp.2020.2.1421

What is the mortality rate for pressure injuries (pressure ulcers)?

Shehabi, Y., Bellomo, R., Reade, M. C., Bailey, M., Bass, F., Howe, B., McArthur, C., Seppelt, I. M., Webb, S., Weisbrodt, L., Sedation Practice in Intensive Care Evaluation (SPICE) Study Investigators, & ANZICS Clinical Trials Group (2012). Early intensive care sedation predicts long-term mortality in ventilated critically ill patients. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 186(8), 724–731. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201203-0522OC

Tanaka, L.M.S., Azevedo, L.C.P., Park, M. et al. Early sedation and clinical outcomes of mechanically ventilated patients: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Crit Care 18, R156 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc13995

Balzer, F., Weiß, B., Kumpf, O. et al. Early deep sedation is associated with decreased in-hospital and two-year follow-up survival. Crit Care 19, 197 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-015-0929-2

Yang, J., Zhou, Y., Kang, Y., Xu, B., Wang, P., Lv, Y., & Wang, Z. (2017). Risk Factors of Delirium in Sequential Sedation Patients in Intensive Care Units. BioMed research international, 2017, 3539872. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3539872

Saccheri, C., Morawiec, E., Delemazure, J. et al. ICU-acquired weakness, diaphragm dysfunction and long-term outcomes of critically ill patients. Ann. Intensive Care 10, 1 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-019-0618-4

SUBSCRIBE TO THE PODCAST