SUBSCRIBE TO THE PODCAST

Are awakening trials just for breathing trials? How do we set patients up for successful breathing trials to minimize time on the ventilator? What role does sedation and mobility play into prompt liberation from mechanical ventilation? Karsten Roberts, MSc, RRT, FAARC joins us now to dive deep into spontaneous breathing trials in the ABCDEF Bundle.

Episode Transcription

The B of the bundle is for Both- awakening and breathing trials. Putting these two steps together on the same letter has led us to believe that they must always be together. Clearly, you must have patients awake to do a breathing trial. Yet, you don’t have to be doing a breathing trial to have patients awake. So though they are not supposed to always be so intertwined, failure to properly awaken patients significantly impacts breathing trials.

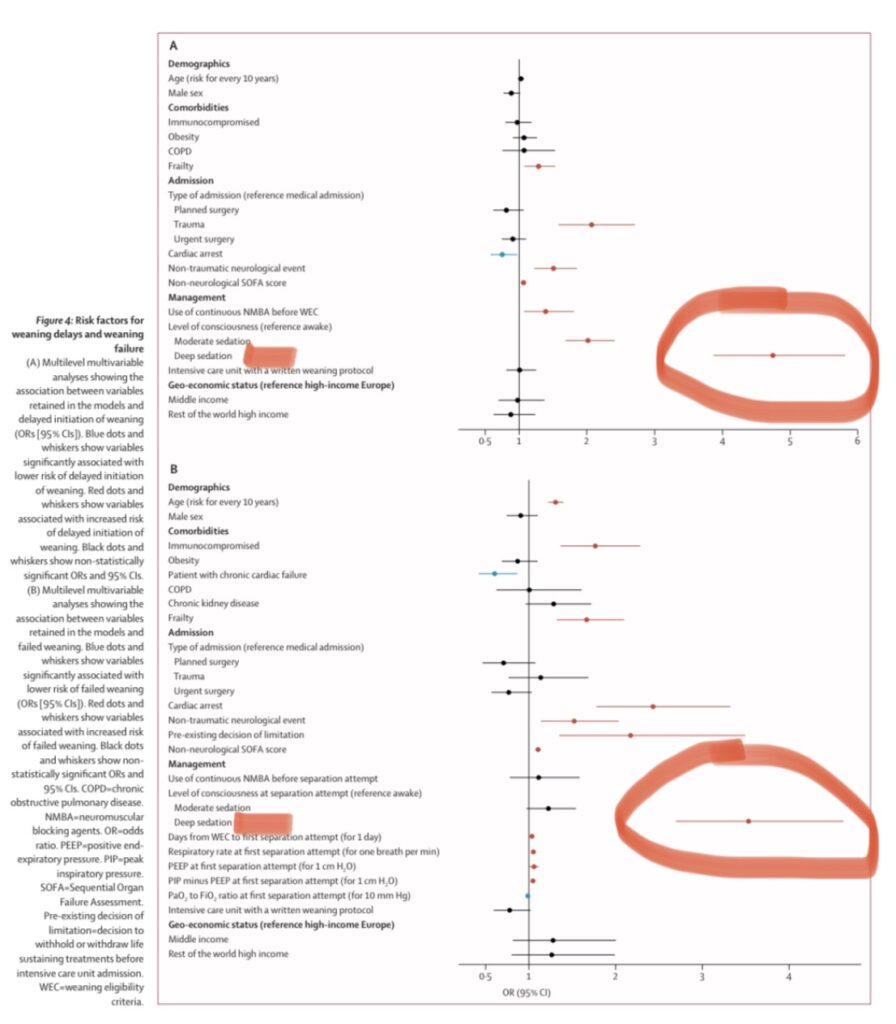

Dr. Ely mentioned the diurnal study in which it was found that sedation was often increased overnight and led to failed breathing trials. Another recent study investigating all the elements that led to failed breathing trials such as timing, management, and epidemiology. They found that the main predictor of a failed breathing trial, prolonged time on the vent, and failure on the vent was….. deep sedation. It didn’t matter the patient diagnosis, acuity, epidemiology… it was US. OUR treatment. By failing to practice the ABCDEF bundle, we set patients up to stay on the ventilator longer and have worse outcomes.

This episode, we have respiratory therapist expert, Karsten Roberts with us to give us the big picture of the power of breathing trials.

Kali Dayton 0:02

Karsten, welcome to the podcast. Can you introduce yourself to us?

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 0:06

Yeah, my name is Karsten Roberts. I am a respiratory therapist and teaching professor at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. I am an RT, RT accs. And I’m a fellow of the American Association for Respiratory Care.

Kali Dayton 0:25

Well, thank you so much for joining us. And for covering the B, the breathing trial of the B part of the ABCDEF bundle, I think there are a lot of misconceptions that are going to be important to clarify today. So let’s just cover the basics. What are spontaneous breathing trials?

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 0:43

Yeah, I mean, obviously, that’s a good place to start. What exactly are we trying to accomplish? So a spontaneous breathing trial is an assessment that we conduct to evaluate a patient’s ability to breathe on their own, once some, some resolution of disease process has come to to an end.

So as patients are healing from injury surgery, you know, ARDS are our patients available? Are they do patients have the ability to breathe on their own without clinical ventilatory support. So spontaneous breathing trials involve some temporary removal of the or a reduction in the level of mechanical support that we’re giving them.

So decreasing the pressure support that we give them or decreasing, take removing mechanical breaths from the ventilator and letting a patient just breathe on their own. And there’s different ways that you can accomplish that through a TPS trial pressure support trials, or just CPAP. But allowing the patient to see to breathe on their own and see if they’re able to accomplish that.

Kali Dayton 1:59

How did we even start doing the breathing trials? Have they always existed?

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 2:05

Um, you know, so there’s been a big push by the Society for critical care, medicine and others, to really make this a part of the AAA threat bundle back in 2013. And really, when this push kind of broadly started, but you know, there’s always been some effort back in the 90s, there was, there was some studies that were done that really looked at what’s the best way to wean patients off mechanical ventilation.

So as long as positive pressure has existed, there has always been some effort made to get patients off and mechanical ventilation. But really, you see, like, Esteban back in like 1997 really start to compare different methodologies of trying to get patients off of SPT, like where we are now, in time in history has come with a lot of evidence based research that’s been done over the last 30 years.

But that, you know, I think that I think it’s safe to say that there’s always been some effort to figure out what’s the best way to get patients off of mechanical ventilation since positive pressure, ventilation has been around.

Kali Dayton 3:17

And I love what I learned from respiratory therapists because I’m sure kind of the things that you as RTs, say we, you know, “We get patients on ventilators to get them off.” That’s the point of mechanical ventilation is to have them independently breathe later. I think sometimes we miss that at the bedside that that perspective of this is a dangerous machine. This comes with risks and repercussions. And we want to get this off as soon as possible.

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 3:43

Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I think that the goal, too, is as soon as a patient is intubated, the goal is to have the tube removed and have them spontaneously breathing on their own, as soon as possible. And I think that you’re right, I think that that we do kind of sometimes miss that perspective, when when we’re caring for a patient for patients day to day, and kind of doing some of the more tasky things that have to be done in an ICU in order to provide quality patient care.

Kali Dayton 4:14

And I think just like sedation practices vary between ICUs I think breathing trials vary between ICUs that a lot of culture impacts how we do them. So what do we know? And what do we not know about the timing and parameters of breathing trials?

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 4:30

So that’s a great point. You know, as much as we want to think that evidence based practices being practiced everywhere. It really isn’t. I think that there is a there are wide. A wide range of how things are accomplished. Sometimes it’s referred to as a weaning trial. And, you know, really, it’s more appropriate that we probably talked about it as ventilator liberation.

But again, And like you said, the cultural impact is different in different places. So I think what we know about, about the timing of spontaneous breathing trials is that it’s associated with improving the, you know, improvements in the disease process. So as patients are showing signs of progression towards healing, then it’s probably time to start working on weaning sedation and getting patients breathing on their own.

So they’re usually performed when patients meet certain criteria, adequate oxygenation, adequate hemo dynamic stability, patients are generally stable and, you know, more awake and more alert. And then, you know, again, there are a variety of ways that the the SBTs are performed now, using a T piece trial where there’s no pressure support, no continuous positive airway pressure CPAP.

Or, you know, using some level of pressure support current, you know, the current ATS SCCM guidelines say that we should be using or tests I should say, chest guidelines say that we should be using some level of pressure support to support a patient’s breathing while they’re weaning from. From that, but, you know, there’s there’s still a variety of opinions and it’s somewhat of a controversial, you know, it’s somewhat controversial how we, how we actually conduct the SPT. So that’s some of the stuff that we know.

Kali Dayton 6:38

Absolutely. I think part of that controversy is the relationship between breathing trials and awakening trials. I think culturally, we’ve missed them, especially since they fall on the same letter of the bee. I feel like even visually that reaffirms this dependent relationship. But in my experience, in Awake and Walking ICU patients are rarely sedated.

We’re not really doing awakening trials throughout their course on the ventilator, we’re not waiting for ventilator settings to be minimal, to take sedation off, it’s just off or it’s so minimal, that it doesn’t really impede a breathing trial. But breathing trials don’t happen until later. So what about this relationship? Are they synonymous? Are they how do you have to be doing a breathing trial to do an awakened trial? Like how did this happen?

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 7:29

So I, you know, I think that that nursing has an obligation to always have a patient as minimally sedated as possible. So I don’t think that spontaneous breathing trials and spontaneous awakening trials are synonymous, they sum they often go hand in hand, they often happen at the same time. However, as you mentioned, there’s you know, really, when we talk about the bundle as a whole, patients really should be awake and alert and tolerating mechanical ventilation.

That’s not to say that they should shouldn’t have full ventilatory support, as long as they’re tolerating the ventilator. You know, you I’ve had patients sit, like wide awake, and be completely tolerant of the mechanical ventilator, or they’re completely wide awake, and they’re not tolerant, if they’re not tolerant, and other than later, then let’s balance out the sedation, and keep them awake, but tolerating the ventilator.

I think when we talk about spontaneous awakening trials, and spontaneous breathing trials, specifically, and how they work is we’re really talking about a patient that’s met the criteria that can have all sedation stopped at a certain time of the morning, or whenever you do your trials. And as soon as they are ready, the respiratory therapist does an assessment of their ability to breathe, and then turns off the ventilator so to speak, we say turn off the ventilator.

But what we really mean is remove the mechanical breaths, put them on positive pressure, spontaneous breathing, and see what see what the patient’s ability to breathe on their own is. And if they’re not able to do that, we give them back full support, cut sedation in half, and then try again 24 hours later. That’s the ideal situation. That’s not always how it goes. Because as you mentioned, culturally ICUs aren’t there yet, but really, if you didn’t buy the textbook, that that’s how it should work.

Kali Dayton 9:39

And I think this is where I see a lot of the struggle is when culturally we think we are doing awakening trials just to do a breathing trial. When the breathing trial fails. The wiccaning trial concludes because the word even just trial vacation interruption. We have this sense of it. This is temporary. We don’t want patients to be be free of sedation, as long as they’re receiving support from the ventilator.

And that’s all cultural. Right? So I think even just that automatic resumption of sedation after a failed breathing trial, is really concerning. Because we don’t understand the risks of sedation. For every drop, it increases, ice acquired weakness and delirium. But why do breathing trials fail?

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 10:21

Well, I think that the breathing trials fail for a variety of reasons, you know, it has to do with underlying disease process. So somebody that comes in with COPD or asthma, it depends on how long they’ve been mechanically ventilated, they can be completely deconditioned. If you have a patient that’s been on a ventilator for several weeks, or, or months, even, it’s going to be a lot harder for them to, to wean from the ventilator, you know, do they have adequate oxygenation at baseline, you know, as soon as soon as a spontaneous breathing trial starts, you have to realize that the patient is doing more work by necessity, and therefore, oxygen consumption goes up.

And that’s going to be more of a challenge for the patient throughout the trial. And so you have all of those things, muscle fatigue, and just generalized weakness from being being deconditioned. And I think that that’s really, really important to consider where early mobility comes in, especially for those patients that have have been so deconditioned from from whatever disease process brought them into the ICU in the first place.

Kali Dayton 11:38

Yeah, there are so many reasons, right. And I think sometimes artists are frustrated because patients are not adequately D sedated enough, right. They’re still pretty groggy. Sometimes it’s hard to tell what’s hypoactive delirium, what’s metabolized station or station was just to newly off. And then I think that gets mixed in with weakness. I don’t know that we’re really panicked, who’s saying “They’re tachypneic, their lungs, their volumes are low, the rate increase, they’re getting diaphragmatic, they’re getting tired.” And we’re not talking about what’s happening with the diaphragm, because you’re, you know, saying, like, it’s very late to you that they’re too weak to breathe. But is that always recognized and discussed at the bedside when there’s a failed breathing trial?

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 12:22

I don’t think it is. And actually, as we’re talking about this, in this very moment, I’m thinking about a specific patient that had a lung transplant several years ago. And it wasn’t well recognized initially, that he hit, he actually had phrenic nerve injury. And, and so he, he, you know, his diaphragm was still functional, it just was a lot weaker.

And there, there are some ideas as to how we can mitigate that, you know, there’s some new or modes of ventilation, such as Nava, that that could potentially help you like the idea was even floated to use a chest giraffe’s and using negative pressure ventilation to gentleman because, because he was so deconditioned, and he had this phrenic nerve injury, there was a lot going into it.

So we even might go further back. Prior to even having positive pressure and even think about other ways of ventilating patients other than other than what we’re typically used to in the ICU. Unfortunately, he ended up back on ECMO and dying before we could really get to the point where he was able to support his breathing on his own. But that’s that’s one situation where we’re where diaphragmatic weakness and muscle fatigue and the strength that patients lose while they’re in the ICU really, really struck me.

Kali Dayton 13:54

And that’s on a team that’s assessing for it, discussing it trying to find the root cause of it. What I see often happening is that we have a failed breathing trial, you know, the party says it’s failed, the nurse comes in, they say their their back end says control, and they resumed sedation, when in reality, that sedation is one of the main culprit of that failed trial.

Yeah, propofol is myotoxic, and then early mobility is impossible. So how are you going to rehabilitate those respiratory muscles and the diaphragm to be strong enough to over to take over independent breathing, if we’ve automatically resumed sedation and taken away the opportunity to rehabilitate.

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 14:33

I think Well, I think even beyond that, I think there’s another important piece that we’re missing here, which is talking about anxiety. I’ve been really interested for quite some time about the psychology of the ICU. I mean, we talk about like about PTSD and post ICU syndrome. But what about the anxiety that patients experience already in the ICU while they’re in, in hospital like or even before they were, you know, I think that it would be really interesting to take a look at the patients that have baseline anxiety disorders and how they do with mechanical ventilation.

There was an a number of years ago that I worked with the psychiatric team at the hospital I was working at at the time to really try to work through some of the stuff but again, it takes a specialized team, you have to have not only a psychiatrist, but probably a psychologist, on staff that can really get to the heart of what the patient’s issues are. And and there could be any spectrum of anxiety that is involved. And, you know, propofol and other sedative drugs probably affect that as well.

Kali Dayton 15:52

I mean, you’re, you’re sedating them. They’re, they’re literally rotting. During that time, they’re atrophying they’re developing delirium, then we yanked them back into reality. And they’re trying to understand what’s going on, they’re having hallucinations, they’re in a totally different world. They are weak, they’re breathing through a straw, and it’s hard to breathe because they’re so weak.

And so it’s I am just trying to imagine what that’s like, suddenly be jerked into this reality where you’re having to work for every single breath, and you don’t understand where you’re at and why you’re doing it. That’s gotta be terrifying. So what is it to keep me from? Is it from just the weakness? And or is it from the very valid anxiety?

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 16:32

And you know, what, I think that it takes a very keen eye from on the on the part of the respiratory therapist, to be able to kind of pull apart which is which. And it’s not, it’s not an easy task. It’s it takes, it takes critical thinking skills on behalf of the clinicians, communication between the bedside nurse and the respiratory therapists, and being able to communicate that back to the team and say, look, I think that there’s probably something more going on here, you know, can we, you know, can we change the medication that they’re on? Can we change?

You know, is there something more that we could be doing here? Should they be getting this much, and in going back to the point that you made a few minutes ago about the way that that patients metabolize medication? You know, I think of patients that are on fentanyl, even on low doses of fentanyl, that that is potentially too much for them, because they’re not metabolizing it well, because of advanced age or whatever. renal function? Absolutely, absolutely. And so we don’t, we don’t always think about that.

And again, it takes clinicians that are keenly aware of every aspect of pharmacologic at attributes that affect them, the spontaneous breathing trial as well. So I really encourage students and therapists that are new to practice, even therapists that have been practicing for a long time to be aware of what the nurses doing, being able to put that as a part of your patient ventilator assessment is what’s going on with the sedation, what’s going on, with the drugs that the patient is on? And why, why or why not? Is the patient being successful? Truly,

Kali Dayton 18:35

I would love for RTs make more of a leadership on that. And to teach their colleagues say, “Hey, they failed this trial. But here’s what I saw during that trial. I’m worried about diaphragm dysfunction, I’m worried about their anxiety, and they look like they have delirium. We need to mobilize them because we need to we can go to the diaphragm, improve secretion clearance clear out there delirium. You know, let’s try that before we restart sedation, or do we really want to restart sedation? Is there an indication for sedation? Here’s what I’m concerned about.”

And just to really stimulate that conversation and bring evidence to the table would be powerful. Because if your goal as an RT is to get them off the ventilator, then you’ve got to be the stewards of that ventilator, which is not just the ventilator, it’s the whole picture.

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 19:23

Yes, yes. Yes, yes. And respiratory therapists are fully capable of that leadership role at the bedside. And I think that it’s sometimes hard for us to see that. But respiratory therapists definitely need to be more involved in the care team and not just getting the work done. I think we need to see ourselves more of a, a career oriented profession and, and less of just getting tasks done throughout the day. We, you know, we can we have the knowledge, we have the skills to be able to assess those things. It’s just applying it and feeling and make and being confident that in our abilities to do that, and you know, have those have those collaborative conversations with the nurses and the physicians, the providers that are, are also caring for the patient.

Kali Dayton 20:32

Yeah, I want RTs to understand how big of an impact they can have at a patient’s trajectory of their course of their time in the ICU, but also their entire lives. Like a respiratory therapist is saying, “I’m worried about diaphragm dysfunction, let’s get them up. And they we help rehabilitate them, they saved them a tracheostomy.”

Which could save them days, two weeks on a ventilator they could save them tracheal stenosis further decline. I mean, they can be that that total course correction in that moment. But again, yeah, I think we’re all trained to be very robotic in our roles, and just go through the process. And I think without critically thinking through breathing trials, we are causing a lot more work for ourselves.

We’re causing days, two weeks longer the ventilator when we get a failed trial, resumed sedation, it’s just rinse and repeat the next day, we never actually get anywhere until the patient’s treatment vague and sent out. And then we consider that a success. What if we consider a tracheostomy especially for prolonged time on the ventilator, as not a sentinel event, but something to really review? You know what I mean, if our in our COVID patients, and we said, “Hey, they’re on a peep of five and 40%, but they couldn’t sustain their own work of breathing? How did that happen? Let’s rewind, let’s look at the whole course of events. Did we practice a bundle here?” What if we took that approach and learn from those moments?

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 21:54

I think that it would change the culture as a whole. And, you know, I go, I go back and forth with the tracheostomy because sometimes, you know, we’re talking about a tracheostomy after only one week on the ventilator. I work in institutions where it’s, you know, a lot of this has to do with early intervention, you know, whether you’re talking about trying to get an SBT or SAT done as soon as possible, or early mobility as soon as possible in the course or tracheostomy early in the course.

I’ve also worked at places that wait a couple of weeks, you know, really awaking waiting, like 14 days before we really pull the trigger. And I think that that’s really the culture that says this isn’t what the what the outcome that we want. And we don’t call it a sentinel event, like you said, but if I think that if we did, I think that it would change the culture and maybe we would, we would be more proactive in initiating spontaneous breathing trials appropriately. And not just like writing it off. Well, they’re not ready. I can’t even tell you the number of times that I’ve seen that note, the patient wasn’t ready for an SPT Well, why, you know, you kind of always have to ask why.

Kali Dayton 23:10

That was just agitation. I mean, they turn on sedation.

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 23:15

Sometimes it would turn out that they they had the the nurse increase the sedation, or increase the pain medication, because they were bathing the patient at 530 in the morning to get them ready for day shift. And then it was a sedation issue, and not necessarily the patient might have been totally ready to come off the ventilator, but they got reached sedated for X y&z reason. And and then a full 24 hours goes by again before they’re even ready to go. You know, and so

Kali Dayton 23:49

Certainly, we don’t need to be doing a breathing trial to do an awakened trial. But you have to do an awakening trial to do a breathing trial.

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 23:58

Yeah, I think that’s the point. Really, the relationship with going back to the beginning of this conversation? I think that really is the conversation, you know, then they’re not necessarily I think you said it perfectly a moment ago.

Kali Dayton 00:02

And what about the timing of it? When is the best time to do a breathing trial, everyone started to do waking trials at five in the morning. For reasons that are unclear to me, what do you recommend as far as the prime time for breathing trial.

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 00:14

So I don’t think that I can recommend a time to do a spontaneous breathing trial, because I don’t think that we have as a literature that supports a specific time to do it. You know, you’re right there, there is a push to do a spontaneous breathing trial at 5am.

So that the patient is teed up to do to be excavated. Now there is literature that shows that when a patient is excavated by 9am, they can get to especially in like in a medical ICU, like what I’m used to working in the patients, if they’re excavated by 9am, can be to the medical floor by 1pm. Decrease, decreases hospital length of stay by one and a half days, which is significant. I mean, it is statistically significant in the the research that’s been done, but I mean, that’s huge, that’s a, that’s a big deal to be out of the ice out of the ICU sooner and be out of the hospital a day and a half sooner, the patient is just that much closer to to their activities of daily living.

So there is that evidence that exists that says we can get them out in the morning, we can observe them throughout the day, and then get them to the floor. So I would advocate you know, it doesn’t necessarily have to be at 5am. But if you can have that patient ready to be excavated by the time rounds, like if your team is rounding at nine o’clock or 10 o’clock, get the tube out while the team is there gathered watching the patient, and then they can get out of the ICU even as soon as that day.

That’s a that’s a big win for that patient. And, you know, then I think that there’s a question of like, Well, should we be doing multiple SBTs during the day Should we do one in the morning and one in the evening? There has there is some some data out there that are there are some studies that have done that. I don’t think that we necessarily know still whether a morning SPT or an evening SBT or even a nighttime SBT and extubation is better or worse for the patient.

We don’t we don’t know that in total. But but we we do have some evidence that suggests that the again it goes back to what I said a little while ago was the sooner the better everything if the sooner we initiate it, the sooner the patient gets activated, the sooner they go home.

Kali Dayton 2:41

And if they’re failing, let’s say because they have apparent diaphragm dysfunction. For example, does frequency improve outcomes it to rehabilitate the diaphragm? Does frequency of that challenge help rehabilitate the diaphragm, the respiratory muscles?

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 2:58

I think that the best evidence that we have at the moment suggests that if they fail, once in a day, they’re likely to fail again. So let’s put them back on full ventilator support. And try again tomorrow. Now that’s not to say that implementation of non invasive ventilation after extubation wouldn’t support them potentially.

So you know, that’s maybe even a whole nother conversation about what happens after extubation. So you’ve successfully passed an SBT you successfully extubate the patient. Now the goal is to keep them off the ventilator. In what way are we going to do that? So ventilator liberation isn’t limited to the criteria that they meet to start an SPT, how they successfully pass an SBT, whether it’s with pressure support, or without pressure support, and then get them excavated? It’s what happens after all of that. After all of that is done. How do we keep them off? Then how do we meet 28 days and 60 days and 90 days off the ventilator?

Kali Dayton 4:06

I think that’s where early mobility is so key in that aspect because we’re engaged in the diaphragm, the respiratory muscles to sit stand walk, and we’re preparing them to be successful after you need functional muscles to be able to cough effectively to protect your airway, clear secretions, drop your diaphragm, take adequate looking volumes sustain your own work of breathing, you need those muscles. So there needs to be a focus even upon intubation. How are we going to set them up so that we’re not having failed breathing trials because of weakness? And riaan? intubations because of weakness

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 4:41

It really goes back to the multidisciplinary approach. So at the very, very beginning, how does the team come together? How is Respiratory Therapy going to function with the nurse and how are the nurse and the respiratory therapist going to function with the physical therapist and the occupational therapist to do the early mobility to do you know even if it’s I mean, this this has been a part of my, my practice in the ICU since the very beginning of my career, I worked in cardiac ICU at the beginning of my career.

And, of course, we know that the goal is to have those patients extubated within four hours of of cardiac surgery. But then even an hour after we get them excavated, they’re already dangling at the bed. At the side of the bed. They’re already up in the cardiac chair, already taking deep breaths and coughing with their pillow. And

Kali Dayton 5:28

after having this their sternum cracked open, why aren’t we doing that in the medical side? Right?

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 5:33

I that. Right? That’s kind of my point. You know, we’re able to do that on the on the cardiac surgery side of things that we all know is super complicated, and can go very wrong very quickly. I think that we should be able to do that on the medical intensive care side as well. And we and again, it’s one of those things that I think that we put in silos and we’re like, well, medical ICU isn’t surgical ICU, and surgical ICU isn’t cardiothoracic surgeryICU.

I’m an advocate of breaking down some of those walls. Yes, those are totally different patient populations. Yes, I totally agree that there are differences in the way that we manage their care and in how they get rehabilitated. However, you know, the physical therapists in that I see working in the cardiac, cardiothoracic ICUs are some of the most skilled physical therapists because of the way that they’re managing those patients. And I’m thinking of two very specific people right now.

They’re awesome. They’re just they’re really, they’re really involved in every aspect of, of that pain of those patients care from and, you know, people like, well, you know, they have their sternum cracked open, whatever, like, I’ve seen, I’ve seen patients that were delirious in the CT surgery unit, have an embed cycle placed and start cycling, and their delirium went away within five minutes, like the patient was like, he like literally turned his head to his wife and was like, “Oh, hi!” from being completely delirious and like, and then interactive with his wife, with after five minutes of pedaling a cycle. And if I wasn’t…… it’s so hard to describe that.

Kali Dayton 7:27

I know! You have to see it, right. You have to see it happen, because it sounds like you’re making it up.

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 7:33

Yeah,

Kali Dayton 7:33

I share that experience over and over again. And I’m seeing that replicated throughout so many ICUs and getting that feedback. This is, this is a real thing. But in some of our protocols, it seems like especially in the medical ICU, when we don’t allow patients to mobilize if they can’t follow commands, well, then they’re just stuck there. So we have to have and I just would invite our T’s everyone to advocate for mobility to be used to treat delirium to treat failed breathing trials to look at the big picture and as we approach these elements of A to F bundle, let’s keep the overall goal in mind and intact.

Kali Dayton 24:15

Sometimes nurses will say, well, RT is not always available. So I can’t do an awakening trial. That’s to me that’s revealing.

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 24:23

That is revealing. I mean, that’s that’s on us.

Kali Dayton 24:27

Or that kind of feeds into the misconception that awakening trials are just for breathing trials. But if a patient comes agitated, respiratory therapy can adjust things on the ventilator maybe help provide more comfort and help treat that agitation. So I think they knew need to be available but you don’t wait till RT is in the room to do an awakening trial.

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 24:52

Absolutely, absolutely. I because respiratory therapists do get busy you know, like we’re we’re the ones that are going on every single transport, I’m in the ICU. We’re doing the bronchoscopy. Even in the middle of the night, you know that stuff, especially if you’re working in a big urban center, like I’m accustomed to, the respiratory therapists that work night shift are just as busy as the respiratory therapists that work day shift. Right?

They’re running around, sometimes even more under resourced than we are during the day, a lot of times. So, so you’re right. You know, it can’t just be like, “Oh, the respiratory therapist is in here. So I’m not going to cut sedation, because they might not come back.” Well, you know, it just takes a collaborative environment and a culture that is willing to have that collaboration, to be able to have accomplish those things.

Kali Dayton 25:46

And to get I’m used to medical surgical ICU where patients are allowed to wake up shortly after intubation, mobilize them shortly after they’ve walked even on PEEP of 18 and 100% the whole time. So you know, they’re awake, but are they ready for breathing trial at those settings? Not necessarily. But when they get to lower settings, we’re gonna put up and CPAP take then for a walk, sit them in the chair. And then we’re looking at extubation and seeing how they’re doing.

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 26:09

Yeah, you and I talked about that before, you know, just in our conversations prior prior to this recording. And, and I think it, it is really important to I don’t want to put those things into silos necessarily. But but sometimes you do have to see the difference between the awakening trial, the early mobility, and the ability to actually wean from mechanical ventilation is different things. They are clearly a part all part of that of the bundle. And yet, sometimes we just have to kind of reconsider how we look at each individual piece of the bundle.

Kali Dayton 26:53

And understand the role they play in the overall outcomes. Right, exactly, and how they relate to each other. So anything else you would want to share with ICU community? We’re gonna do another episode with you later about the RT role and things that get in the way of RTs has been able to really optimize their role, but what else would you have them know about the ABCDEF bundle and how this all ties in together?

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 27:17

Um, I think that, that we really just have to think more about the collaborative relationship that we have, we all play a role in it. You know, we can’t do this individually. We can’t, you know, the, the nurse can’t be over here doing their thing, the respiratory therapist can’t be over here doing their thing, and not communicating the communication, the collaboration, and the joint effort to improve patient outcomes has to be central to this process.

And and then being able to then communicate, make recommendations to the physician staff or the provider staff that lead to better outcomes. It’s, you know, we’re continually monitoring, we’re continuing, continually reassessing. And, you know, our path, our paths do cross our community, you know, so the respiratory therapist needs to be knowledgeable about what the nurse is doing. And the nurse needs to be knowledgeable about what the respiratory therapist is doing not to step on each other’s toes. You know, we got to stay in our lanes, but

Kali Dayton 28:32

but we can’t utilize each other’s expertise if we don’t know what that expertise is.

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 28:36

Exactly. Yeah, absolutely. So I think that that at the end of the day, that’s the most important thing is the collaborative relationship between nursing and respiratory therapists.

Kali Dayton 28:47

And that’s what I’ve seen people really enjoy as their teams really start to make this transition is that they get to know and trust and work closely with their colleagues. They feel supported, things run smoother, they see patient outcomes improve, but they just have fun. It’s fun to watch them actually talk to each other.

We’re, I don’t know, I feel like in COVID, they didn’t really other than vocera to say, “Hey, the alarms beeping” and our RT is like, “Well, give them paralytics.” Now, it’s, “Hey, we have these patients, on ventilators. ” Rt is saying, “PT, when are you available? RN, what time works for you? Let’s make this happen.” And then they just make magic happen. They see it and they feel supported in their roles. And it’s a really beautiful thing. And that is the ABCDEF bundle.

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 29:32

That Yeah, that’s exactly right. I mean, I think that there’s so much that we lost during COVID. I think that that we need to get back to a place where it is fun, and where we are where we enjoy the community that we work with. I don’t think that that’s like, overall true, but certainly we’re at a different space than we were three or four years ago.

You know Certainly lost the ability to seek out the physical therapists and say, “Hey, can we walk this patient today?” Because it just wasn’t possible. And, and you’re right it once we, once we start having fun and we have those collaborative, multi disciplinary relationships that we are so good at having it just, it makes everything better, it makes our ability to cope with the tragedy that ICU is sometimes so much better. And then again, if we can be in a good space, with our own well being and with the the well being of the team, the patient is the one that ultimately benefits from it.

Kali Dayton 30:49

Absolutely, it’s been tested, tested and proven and I completely agree that this is going to be the key to our healing for the pandemic. And as we all understand the true purpose of breathing trials and how to optimize them. We’re gonna get our patients off ventilators much sooner, walking out the doors and actually going home to not come back. Thank you so much Karsten, for everything you shared. I’m looking forward to your future episode. And we’ll have you back on. Thank you.

Karsten Roberts, MSC, RRT, FAARC 31:16

Thanks, Kali.

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Resources

Figure 4: Risk Factors For Weaning Delays and Weaning Failure

The Dirunal Study- The impact of increased sedation overnight:

Seymour, C. W., Pandharipande, P. P., Koestner, T., Hudson, L. D., Thompson, J. L., Shintani, A. K., Ely, E. W., & Girard, T. D. (2012). Diurnal sedative changes during intensive care: impact on liberation from mechanical ventilation and delirium. Critical care medicine, 40(10), 2788–2796.

Deep sedation is the primary predictor of failed breathing trials:

Pham, T., Heunks, L., Bellani, G., Madotto, F., Aragao, I., Beduneau, G., Goligher, E. C., Grasselli, G., Laake, J. H., Mancebo, J., Peñuelas, O., Piquilloud, L., Pesenti, A., Wunsch, H., van Haren, F., Brochard, L., Laffey, J. G., & WEAN SAFE Investigators (2023). Weaning from mechanical ventilation in intensive care units across 50 countries (WEAN SAFE): a multicentre, prospective, observational cohort study. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine, 11(5), 465–476.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE PODCAST