SUBSCRIBE TO THE PODCAST

We know that early mobility is a potent tool to prevent and treat ICU delirium. How does it impact cognitive function 1 year after discharge? What do “Early” and “Mobility” REALLY mean? How has drastic variation in methodology in the research led to the confusion and conflict we now see in early mobility practices? How can we optimize early mobility in the ICU? Is it safe and feasible to mobilize most patients within 48 hrs after intubation? Is there evidence to support restrictive mobility parameters by ventilator settings, vasopressors, etc.? How can intensivists lead and support their teams to master the full ABCDEF bundle? Dr. Bhakti Patel shares with us her recent research and invaluable insights.

Episode Transcription

Kali Dayton 0:03

Dr. Patel, welcome to the podcast. Can you introduce yourself to the listeners?

Dr. Bhakti Patel 0:07

Sure. I’m Bahkti Patel. I’m a pulmonary critical care physician at the University of Chicago. And thank you for having me.

Kali Dayton 0:15

And I’m really excited to have you on because I’ve been a big fan of your recent study that was published, I guess it wasn’t done so recently, but it was recently published. Tell us about what you’ve been up to.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 0:26

Yeah! So we did a clinical trial (1) for patients who were newly on mechanical ventilation, so within 96 hours, and they’re independent at baseline, and we enrolled them in a study to receive early physical and occupational therapy, or usual care. And our main focus was to see if patients would have long term benefits, specifically in terms of their cognition.

So we we published that trial, back in January of this year, we enrolled 200 patients, and we found that early mobilization actually improved cognitive impairment by almost 20%.

So if you did that intervention to five patients, you could prevent one patient from having, you know, cognitive impairment a year later. So that was really exciting. Because as a practicing ICU doctor, there’s there’s actually no other tools really to prevent the long term cognitive impairment and disability that we’ve seen in patients who survived the ICU.

Kali Dayton 1:32

And you personally were going to these people’s homes, right?

Dr. Bhakti Patel 1:37

Yes, yes. So we, you know, because we are located on the south side of Chicago, a lot of patients don’t have lots of means to come into post ICU clinics, to do the data collection, you know, a year into their survival period.

So we, if they couldn’t come to us, we came to them. So it was actually quite eye opening, to see that there’s sort of larger barriers beyond just survivorship from the ICU. And it was also eye opening for our therapy staff, because typically, when they’re sort of deciding whether someone’s safe to go home, you know, we do ambulation tests or things like that.

And then when you let go into someone’s lived environment, you see that there’s no straight hallways that are clear of all obstacles that people have to navigate through different, you know, their lived environment.

A lot of families were living in small, cramped apartments, multiple appliances and beds all in one big room. And so I think it gave them a window into why patients might fall or might have you know, readmissions and things like that. So it kind of adapted, sort of the safety check for mobility for future patients when they were leaving the ICU.

Kali Dayton 3:00

Oh, interesting. And I wonder if that might influence how we prioritize patients to certain demographics, maybe even more important to mobilize sooner and to keep it even stronger? Like maybe they’re going to need to leave at a better state? Yeah, for sure. Or to have the support to continue to rehabilitate from a lower level at home.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 3:24

Exactly. And, you know, thinking about, even how can they go back and forth to all these appointments or, you know, go to outpatient rehab, and what’s possible even to read that rehab at home, I think, taking into account, sort of the environment patients live in and the resources available.

A lot of the people we visited, no spontaneously would say you should come and we before that, it gets dark, because it’s an unsafe area. And you know, as a provider, I’ve said to people who are trying to, you know, rehab, like “go for a walk!”.

And that’s not a simple ask of patients. So. So I think that was eye opening for me, because I, you know, you hear about stuff in the news. You know, I’ve definitely been in parts of the city that didn’t feel quite safe, but to see patients like on their day to day experiences to be in that environment.

It’s quite a challenge. And it’s it, it provided sort of the context and the humanity that they came into our ICU with and that you, you realize, like what they’re up against, as they’re trying to recover and get back to their, you know, everyday lives.

Kali Dayton 4:46

Wow, on this podcast, we’re talking about, obviously humanizing the ICU. Seeing our patients as individuals understanding them. I think we’ve talked a lot about what kind of music they like what their what career they were doing, how many children they have, you know, those kinds of things? I personally don’t know that I’ve really been focusing on what is their home environment? Like? What kind of life? Am I’m sending them back to? And are they going to be prepared for that life?

Dr. Bhakti Patel 5:14

Yeah, I think, you know, there’s, there’s unique challenges and you don’t realize it, and people don’t really talk about it. And it’s hard to get stay focused on it, when you’re distracted by, you know, the acuity of the day, I don’t know that there’s enough time in the day to really understand but seeing is sort of a little bit of believing.

And I do think that, you know, some of the things that a lot of patients would sort of say is that, you know, I just have all these appointments, I have all these things, and it’s be it goes beyond scheduling and the the navigation of it all, it just becomes a little bit overwhelming.

And so it was, it was an eye opener for me, I think, you know, to function in the day, ICU providers who see, you know, a lot of life and death, you have to sort of almost to maintain objectivity and sanity, you have to sort of almost dehumanize everybody.

But I do think it is a richer experience to know who your patient is, even if they can’t reveal themselves to you. And it hurts more when if they if things don’t work out the way you want. But in the end, it’s a richer experience, I do think that patients feel valued, because they think, you know, they do feel like kind of pieces of meat on a bed, if you don’t do that. And, and their families. Remember that.

So I think really getting a rich experience of you know, where people live and what they do during the day. And, you know, I think as people think about how to manage the, you know, post ICU recovery space, really thinking about learning there about the home environment with a visit, because it’s like, you can’t really describe these things.

You have to sort of go home and see it. And so I think, and it gives you a better picture of what people are dealing with. And maybe we come up with better solutions, then sort of in a clinical space, I guess.

Kali Dayton 7:28

And obviously, you were aware of the cognitive impairments that follow and ICU stay. That’s why he did this study. But being in those environments, and now doing this study, and having such a focus, how has it impacted your approach when you’re an attending?

Dr. Bhakti Patel 7:46

Yeah, I think it’s made me more mindful about how much support people are going to need, the processing speed, the executive function is definitely different than what it was before they were ill.

And if they don’t have a social support, then even if we can create, like a resource safety net for patients, you know, with multiple appointments, and no specialty visits, and things like that, it becomes hard to navigate that space.

So, so I think about it, you know, really kind of, personally and intensely as soon as someone decides to intubate somebody, that I’m just I start sort of a mental clock in my mind, like, how can I find my window to get this person up and moving, so we don’t lose this?

But we don’t lose, you know, their cognition, their strength, their ability to function, because, you know, everyone’s sort of focused on making sure they live and I’m sort of like, “I don’t want to mess up their function” by you know, in that process.

And so I think I think my, my role has now been to be someone that’s a bit more provocative and shocking to people, because I think everyone sort of know, like, “oh my god, there’s all this drama, this person is really ill, like, we need to do these procedures and do all this stuff.” And I’m sort of sitting there saying,

“That’s great. But you know, one really important procedure today is to awaken this person, and get them up out of bed and like, how can we orchestrate that and make that happen?”

And, you know, I know now the house I’ve kind of know, that’s my stick. And so they tried to find those opportunities. But I think, you know, they they also under are starting to learn that there’s there has to be precision and what that means.

You know, it’s not just like hold a sedative and then you know, check a box and then not necessarily wait for them to wake up or pull the sedative at a time where a therapist isn’t there. You know, it is some coordination of things and sort of, in my mind And ensuring that at a minimum, they set up in bed. Even, you know, the therapist, and I joke about, I don’t know, this is like an old reference, it’s probably going to date me.

But there’s this movie called “Weekend at Bernie’s”. This man named Bernie is actually dead. But every time you, you play music, he starts dancing, and nobody realizes that he’s actually not alive, or he’s in a coma or something like that. And so, you know, I, sometimes the therapist or the nurse or the, you know, the someone on the team will be like, we’re, they’re not doing anything, you know.

And I was like, well, let’s make it weekend and Bernie’s in there, and, you know, turn on the music, and they might just come alive. And so we joke about it. But I do find that sort of that upright position being the minimum dose, I’ve seen many times patients all of a sudden are like, Oh, I’m out of bed!” and their eyes open, and they kind of naturally right themselves in bed.

And if you sort of stop propping them up, they’ll sort of try to, you know, sit up a little bit more, and it’s that nonverbal awakening of the mind putting a task to something that I think will, will be the thing that preserves that cognition. And so, you know, we do a lot of weaken and Burmese if we can’t, you know, we’ll have someone fully awake.

Kali Dayton 11:23

Absolutely! That’s something that you kind of have to experience yourself. And it goes against the way, I guess the intuition we’ve been trained to have, or maybe naturally have to, if someone’s not open their eyes, promptly following commands, moving their legs out of bed, it’s not really an exciting prospect, to do the work for them or to have to get the equipment to get them up, right, it doesn’t make sense at some of our protocols and our ICUs say that patients are not to be mobilized until they’re following commands.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 11:56

Yeah, and so it’s sort of like, the patient has to then run through like, five fiery hoops, right? Like, we’ve definitely handicap them, because we, you know, give them Saturday, we don’t hold it, we give too much. And then we think that despite that, they should just, like break through and like, maintain their cognition. I just think that’s ridiculous.

You know, if you, we don’t, when someone is under general anesthesia, which these patients are, you know, the anesthesiologist, you know, takes it off, but it’s sort of looking to see, can they breathe?

Can they protect their airway,? You know, to say, like, you’re recovering, they’re not necessarily saying do you have to follow all commands, you know. And so, for us to think that that cumulative dose of general anesthesia over days is not isn’t isn’t a big barrier to get people, you know, awaken following commands is, is interesting to me.

I also find that, you know, of all the barriers that we say there is to mobility, sedation is the most modifiable one. You know, I can’t change the severity of illness, you know, I can’t change like the disability they came in with, but I can change, you know, how much sedative patients get.

And so when I, when I see in trials, that, you know, sedation was the barrier, I think to myself, you know, it’s the providers that are the barrier, because, you know, you you can awaken patients, it’s just that your own mind has set a limitation to.

Kali Dayton 13:39

The culture that they’re immersed in, we thought that it was automatically start sedation on everyone meeting rather than negative three, then they would interrupt sedation, for mobility, and then resume it. Yeah, and that we saw that throughout, I looked like most of the patients, and were listed in that study.

So of course, you know, 12 minutes more mobility didn’t make that much of a difference. But that was so revealing of what most of our culture is started briefly “Stop it, resume it”. And so there isn’t an expectation for patients to really be free of sedation, avoid sedation, minimize sedation, or to turn it off.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 14:24

Yeah, it’s interesting, like for the amount of, like, I joke with my team, sometimes that you know, for the the amount of therapeutic benefit we put on sedation, you would think we’d have cured critical illness, right. So like, people say, like, “oh, they need to say sedated because they’re hypoxic.”

Well, I’ve had patients on full sedation, full comatose, still hypoxic like that’s not going to change anything. I’ve seen people use it for vent synchrony insurance. It can work for some patients, but sometimes the respiratory drive will not go down even with sedation like patient will be in a coma and you’re giving more and more that dyssynchrony is happening.

That’s because respiratory drive and effort is not just based on like a sedation pathway, you know, it’s it’s based on how injured your lungs are, how inflamed you are like what your pH is like. So your brainstem is like more complex, then what we can think propofol and versed can do.

Kali Dayton 15:22

And is it worth the price? The price that patients are paying for that sedation?

Dr. Bhakti Patel 15:30

Yeah,

Kali Dayton 15:30

and we’ve associated with severity of illness with sedation. So, “the sicker they are, the more sedation they need”, or “the longer they’re going to need sedation because of that acuity.”

And there are times obviously, if a patient can oxygen with movement to stop the movement, but generally that doesn’t that that belief system doesn’t hold up. And it’s not beneficial for patients?

Dr. Bhakti Patel 15:53

No, it’s very, like it’s very paternalistic, right, I think, in a setting a care setting where you feel out of control, people are looking for control, and it is dramatic, and it is scary to have someone you know, on the brink.

And so people think a machine or medication will give them control so that they can orchestrate things. And I guess my bias is, the more we think we’re in control, the more we’re harming people, you know, I I feel like the physiology of the body is too complex for us to fully understand the magic. And so our goal is to not sort of quelch down that magic, in service to our need for control.

And so, you know, sure if someone’s injurious, you know, self injury, like pulling out there, etc, I get that, but it’s probably pain. And, you know, we should treat their pain first. It might require some verbal anesthesia to and might require, you know, it’s sort of thinking that a drug is going to make someone behave is sort of a crude instrument for something that can be just as simple as like holding their hand and explaining like what happened.

And yeah, they might not remember, but at least, it’s like less damaging than then verse said, you know, so. So yeah, I do think that a lot, that the hardest things that we do in the ICU are the ones that matter.

And this, the shortcuts that we take are the ones that damage and so. So I do think that we have to be really careful about what we think the therapeutic benefit of sedation is. And, you know, I have yet to see a study where sedation is helpful. You know what I mean? Like? Yes,

Kali Dayton 17:50

I’ve even ARDS studies, right? What are the I guess that was paralytic? The Rose study(2)? Yeah, they were evaluating paralysis, but, I mean, they had increased sedation, probably to do the paralysis. And they stopped it because it was so dangerous.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 18:03

Yeah. Yeah. And like always, exactly. And they’re, you know, their usual care arm, you know, with light sedation, and no paralysis. And sure, they didn’t achieve that for all the patients like, but you know, a third of them could be in a light sedation approach, which tells me that one of the three times were just prescribing it just because we labeled it as ARDS.

And so I do think that we have to be careful about sort of saying, like, “certain conditions are just so severe that like, you know, we gotta knock them out” kind of thing. Because the the problem is sure, at the initial phase, you know, they have really bad lung injury, you don’t want to perpetuate that lung injury with with your ventilation strategy being out of control. So I get that.

But you should set a clock in your mind that, you know, the moment you get your opportunity, it, you should undo what you just did. And, and typically, I try to undo it, if I have, if I’m forced into that mode, like within 24 hours, because I’m just thinking, you know, “yesterday they were inflamed, they were under-recruited, their antibiotics had just started. Today, it’s 24 hours and you know, things might be better, they might not need as much as I’m giving them.”

And I think people don’t know how to stop, they just keep going forward. And they sort of remember how bad it was yesterday that they forget to see could be better today. So I also, you know, when I when I chat with the team, you know, like “Let’s see what they what they look like today, like let’s awaken them and see what happens.”

Everyone kind of is like, “Well, yesterday were like…” and them I’m like, “You know, yesterday I was in a bad mood. And I was acting out and I was grumpy but you know today I feel a little bit better. So maybe this person could have that same experience that yesterday was not a good day for them. But we did a lot of things and they might actually be better.”

And we just need them to reveal it to us because we don’t believe it. So I do think the, the holding on to the way that like the things that we did the day before, and thinking that that’s having the same benefit as it is now is a problem.

Because as you know, in the ICU, there’s no stability, but it could be, you know, patients are getting better, and you are the one that is preventing them from revealing it.

Kali Dayton 20:38

And you’re driving that because you understand the risks of it all, you’re doing a risk versus benefit for these patients. You mentioned, you’ve mentioned o’clock, and in my mind, it’s an hourglass.

Every time you intubate someone and start sedation, you flip that hourglass, and their function, their cognitive capacity, their muscular system are those grains of sand that are just dropping. For every drop of sedation, you’re losing that function.

And we all need to be watching that hourglass and be very aware of what’s being paid for that sedation each time and then use that as a guide to say, “Is it really necessary? Is it worth this price? Can we can we stop the clock?”

Dr. Bhakti Patel 21:22

Yeah, yeah, for sure.

Kali Dayton 21:24

And so you had a really, you have a really good team, it sounds like you guys have a good culture, good environment. But tell me more about the methodology of this study.

How did you approach mobility? You and I were in a conference recently. And someone was presenting what they did for their team to be able to mobilize patients with femoral lines for CRRT and their target, they showed a slide where they showed their mobility protocols.

And they said, it said that unless the PEEP is less than five, and Fi02 is than 60%. That was the threshold for mobility that cannot mobilize if requirements were higher, higher than that. And I’m like jumping out of my skin.

And you spoke up and you said that’s probably the biggest barrier, not the femoral lines, the biggest barrier your protocols. So tell me more about how you approached mobility, what kind of protocols or thresholds these patients were benefiting from?

Dr. Bhakti Patel 22:22

Yeah, so. So we had the benefit of doing the original study, or the our team did, my mentor and the therapist on this study, where their main outcome for the 2009 Lancet study (3) was just:

Are you independent or not? Did you maintain your independence? So a lot of the protocols were kind of derived from that. And the, the criteria to initiate therapy was primarily on sort of looking at extremes of physiology.

They weren’t really based on settings, which I think is important. So, you know, if patients had a respiratory rate, you know, about 40, and we’re needing, you know, we’re saturating less than 80%, you know, on whatever settings, they are, then, you know, from a hypoxemia standpoint, thing weren’t ready.

Or, you know, if someone, you know, had a heart rate above, you know, 150, or heart rate less than 40, you know, those sorts of things. So we, a lot of the criteria that we use weren’t based on like the, the amount of support, but more the output of what the patient was showing us.

Because we felt that if we, if we picked a support as a threshold, like a PEEP value, or an Fi02 unnecessarily, then then the team’s like, inability to titrate appropriately could be a barrier.

You know, they may not need, like that double digit peep, or, you know, they may not need that 80% Fi02. And if we use that as a threshold, someone can look at the settings on the, you know, on the vital signs sheet and say they’re not ready for therapy and move on.

And so we were saying, you know, what’s physiologically sound to do, you know, they’re not their heart rates, not above 150, the respiratory, it’s never 40 Because we know, these things will change when they move. And we want to make sure that we have a little bit of a buffer to make that movement happen.

And so, so when we did the trial, that sort of the criteria are used, and and if and I think the thing that was a little different was that, you know, if a patient on a given time of the day had violated one of the criteria to move, you know, it wasn’t like,

“Okay, you’re done, you’ve lost your chance for the day”— we would find a window of opportunity later, because maybe, you know, they’re, you know, people’s titrate and now their saturations better, or perhaps the you know, they just needed more opiate because they were having to kick me out, but now that’s better.

So we really use that as a as a threshold. We also didn’t have a criteria saying you know, “awake and following commands”. Because I think we knew that you know, that the time that you choose to decide with someone’s awake is highly dependent on what drugs they’re on and how long they’ve been taken off, you know, and so we decided that that’s not, you know, a criteria.

So what ended up happening is it typically, you know, if a patient was on study, we tried to get us windows of opportunity and sort of coordinate between the therapy team and the bedside staff to say, “Okay, what procedures do you have going on today? What’s what’s going on? And what’s a good time for us to do this?”

You know, patients generally got awakened at whatever standard time the unit sort of decided. But we would get a sense from them, you know, “What’s the time to awakening? Is it immediate? where some patients like wake up and kind of start a sort of, like, where am I kind of situation and if there was immediate awakening, then the therapist would literally be there, right at the awakening.

If it was an awakening that was taking some time, we would sort of check in regularly say, “Are they awake? How awake are they?”- just trying to get the most out of patients in those scenarios. And then, of course, if patients were awake, they wouldn’t get the sedatives restarted unless they’re agitated, which was sort of the the typical, you know, interruption protocol that, you know, my mentor had, had shown was, was beneficial.

So that’s sort of how we made sure both groups, regardless of intervention, or control, got the daily interruption of both sedative and analgesia, allow time to awaken and then don’t restart the dose, unless they’re agitated. And when you restart, you start at 50% of the dose.

And so over time, everyone just sort of needed less and less just just because that’s the cadence of their illness getting better. And I think, you know, it worked pretty well, for us. You know, we did almost 700 sessions for patients, we did them early in the course, like within, you know, 48 hours in mechanical ventilation, they were, you know, achieving a lot of mobility milestones.

And without that sort of coordination, we saw what happened with the usual care group is that if you don’t have some of that regular communication, trying to find windows of opportunity, it ended up getting delayed, just by default to, you know, for four or five days, typically, when they’re extubated.

And so I really think the key to the methodology was that care coordination, in addition to the sort of not just focusing on strength, but also doing occupational therapy as well. So what that meant was, when patients were awakened, they did their typical bed mobility exercises, either with assistance or not, but when they sat up, you know, they would simulate activities of daily living.

So my job early when I was kind of new at this was to bring the socks and so I would bring the socks and, you know, the therapists would sort of try to engage the person and show them a sock and say, take this in your hand and try to put your sock on and that sort of put motion into context.

You know, there was also putting your glasses on, if you had hearing aids have making sure those were on sort of reorienting a patient to the environment.

And sure, you know, the first day they might not be able to put their socks on, but just the hand motion, the interaction, trying to put context to movement, I really think was the thing trying to awaken the mind, as opposed to just awakening the body.

And, and I think that, you know, one of the lead therapists Her name is Cheryl Aspro, she’s an occupational therapist. And the running joke was that you could never if you by accident said, “Oh, physical therapy is here, she would remind you that occupational therapy is here.”

Kali Dayton 28:56

Yep, I refer back to Episode 137, they really distinguish between those two roles and disciplines, because they are distinct.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 29:03

They are distinct. And I do I do think that, you know, because otherwise, you could focus on, you know, sitting, sit to stand over and over again, you know, and, and you ignore the arms, you ignore the cognitive work, you know, she would talk to patients and say, “Today is Monday, What’s tomorrow? Oh, it’s Tuesday.” You know, it’s just kind of doing that little orienting sort of cues.

And because they worked in teams, you know, physical therapy and occupational therapy, they would sort of cross train in some ways. So I find an occupational therapist, doing PT tasks, and then an OT doing, you know, our PTs doing OT tasks.

So I think that was, I think the key ingredients were to make sure that it happened with high fidelity was a team that’s cohesive and works well together.

Criteria that understands the acuity of a critically ill patient. Like we’re never going to get someone who’s like off off pressors or, you know, on minimum oxygen and PEEP of 5 or less. you know, all those things are like someone who should just get liberated from the vent, and they could probably move faster because they have, you know, no restraints now.

Kali Dayton 30:19

But by then, we can’t!

Dr. Bhakti Patel 30:21

Exactly.

Kali Dayton 30:22

If you wait to that point, it’s going to be much harder. Did you see that? In the usual care group? Did you see a difference in patient’s functional status, but also the workload required to do early mobility with them?

Dr. Bhakti Patel 30:36

Yeah, I mean, they, you know, when they left the hospital, you know, they had the same rate of independence that the previous trial shows, so still, like, you know, half that of the intervention group.

So we still saw that, you know, 30% difference in functional independence, and which is like, you know, I think it’s I was put into context of, “I walked into the hospital, and now you’re telling me, I only have a one in three chance of walking out?”

Like that’s, you know, with the same independence, or similar independence that I had before? That, you know, and that’s because, like, you thought I just couldn’t do it, or it was too hard.

You know, I think patients would value Yeah, of course, they want to survive, but they want to thrive, right, they want to start out at a pace, close to where they were before, or at least where it’s attainable to get back to where they were.

So yeah, the patient in the usual care arm, you know, they were weak. And so even though they were like, physiologically ready, right, like they’re not an event, or their blood pressure was like, perfect, and they’re not on these drips, and everyone feels so safe now doing it, like they can’t do anything.

And they couldn’t do it for as long because you’re now asking someone who has lost so much muscle mass to do intense exercise, like they’re going to show you your cardiovascular and fitness like they’ve lost it.

Kali Dayton 32:04

Do you perceive that as being more laborious for the teams to start moving them at that point?

Dr. Bhakti Patel 32:10

I think it’s less. I mean, laborious, in some ways, is better, because there’s less drips, less things attached. You know, you’re not doing your line management and all that. But it’s less rewarding, like they they don’t do as much, you spent a lot of time and they do nothing.

You know, a lot of the therapists sort of are like, “Fine, that’s like 20 minutes of my time that I don’t feel like made any impact.” You know, trying to get them to lift a finger. Exactly.

Or like, you know, give them a tennis ball to squeeze. I mean, it’s what what can you can you, if you can’t physically sit up in bed, like you’re basically going to, you know, long term rehab or subacute, rehab, you can’t you can’t do acute rehab, like for us.

Even if someone couldn’t go home independent. If they got to, if they could tolerate acute rehab, like, like, a longer duration of like, you know, exercise in the rehab, we thought that was a win.

Because I felt like sub acute rehab, you know, had a shortened time that therapy more time for them to like, just be in bed waiting for other things to happen. And so even if someone wasn’t fully, you know, functionally independent at baseline, if they went to acute rehab, we felt like that was a win,

Kali Dayton 33:24

Because they were going to actually have expectation of getting home and being functional exaggerated that way than just going somewhere to park.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 33:32

Exactly.

Kali Dayton 33:33

And so you’re a physician, you’re an intensivist, you’ve been an attending, researcher, you were bringing the socks into the room. So tell me what it was like for you to be that intimately involved in these therapy sessions? And what did you learn from it? And how has that impacted how you approach care now?

Dr. Bhakti Patel 33:54

Yeah, I mean, you know, my approach has always been that, like, there’s no task that’s beneath me, you know, that says, This is not my job and your job. Because if I if you go in into that role thinking that then then your team is not cohesive. And people are, you know, this was a unfunded study.

We didn’t pay the therapists, they volunteered their time and they did it. The nurses, you know, they they weren’t, you know, investigators and, you know, from, from a bedside nurse perspective, when you’re trying to keep your room tidy and clean and, and like, you know, calm and then for us to come in and be like, awaken your patient, let the alarms go off, set them up, rearrange all your lines, you know, that that’s chaos, and especially after you’ve just kind of created that Zen in the room.

Kali Dayton 34:50

Maybe they’re used to a consistent Zen, right? It’s really disruptive when it’s a change. Anything new is hard.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 34:59

Yeah. So, you know, so we did things like, you know, just to kind of understand the ask because it’s not like, it’s less work, it’s more work for sure. And so, you know, I was like, “Well, if I bring the socks in the room, then every, there’s one less barrier to stand them up.”

You know, because they’re, they have their socks on now. And, you know, if the nurse is sort of, like, not so jazzed about us, like coming in and do this, like, sometimes the therapist and I would bring sheets or like, “We will change your sheets!” you know, because they’re getting out of bed. So we changed the sheets.

And the goal was to make them look just as good as they did, like when we left the room. And I think, for the for the nurses, and respiratory therapists, and even the primary team, like when they saw the purse, like the patient do something that they just could not even imagine doing it all of a sudden, lit this like spark, in their mind be like, “Oh, that’s a person, and I should do everything to keep them themselves.”

And you know, that I wish I had like a, I’m gonna have enough patience to really prove this. But like the number of times someone saw someone walk down the halls, and then all of a sudden, when they weren’t planning on extuating them, they’re like, “We’ll probably extubate them today!”

You know, those sorts of things that awaken the mind to sort of be like, wait, I’m not, it’s not just like, you know, set it and forget it kind of thing, care that maybe I should change direction, because this person is showing me that they’re way better than I thought they were, you know, in the morning.

So, yeah, you know, I think I think doing those things, I think when you do trials like this, and interventions like this, where it’s multidisciplinary, it’s collaborative, it’s based on a team, everyone on the team has to be willing to kind of do tasks that aren’t really in their wheelhouse. And they can be as menial as possible. But that’s, that’s this, like, the culture that needs to, to be reinforced, and make sure that these interventions happen with like high fidelity.

And, you know, I think like, these aren’t aren’t trials, where you can like manage it from your office. If you want to make sure that, you know, patients get the right timing, like you have to, it has to be all hands on deck, which I’m sure you know, the generalizability of that, of course, gets undermined.

But if we’re going to think about a resource intensive intervention like this, we can’t sort of, we have to first prove that in its truest form, it has benefits. And then if we can show that, then we figure out how to make it happen on an everyday kind of basis. But we can’t sort of look at diluted versions of the intervention and then say, “Oh, it doesn’t work.”

Kali Dayton 37:50

Like the TEAMS study (4)?

Dr. Bhakti Patel 37:51

Because I well, so I, you know, I don’t I don’t want to like, you know, I think I think, I think other and I think everyone has a different idea what an intervention is. And that’s the problem of this space.

Kali Dayton 38:06

That’s the plague of early mobility,

Dr. Bhakti Patel 38:08

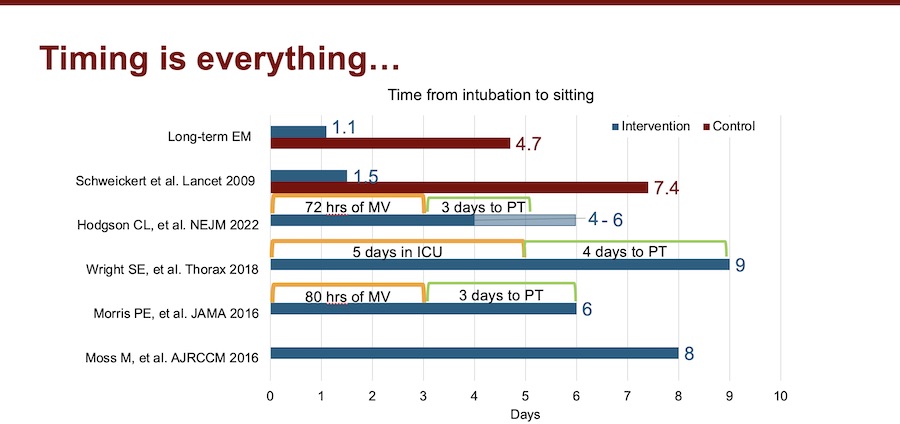

Exactly! For study for an intervention that has the word “early” in it, everyone has a different idea what the timing is. And when I looked through the literature, like as we were trying to get this paper published, you know, I was looking through the literature, because everyone’s looking at, you know, other published studies and sort of saying, like, “How is this different?”

There was no clarity in prior trials of the timing! Which I, which I find shocking, because if we’re, you know, it, mobility works, because it works alphabetically, because it’s in the ABCDE, right? But the reality is, like, even when we talk about mobilization, everyone just says, “It’s mobilization.”

They don’t talk about timing. They don’t talk the time from from ICU admission. And if it’s in a mechanically ventilated patient, they never talk about it time from intubation. And I think there should be transparency in and I think there should be a standardization of what that is.

Because to call yourself “early activity”, but that activity when center around intubation is four to five days later, I don’t know if that’s a really and I think our study shows that.

Kali Dayton 39:20

I’m going to share with everyone, if it’s okay, the slide that you created you, you made graphs(7), and you showed all these main studies and showed the timing of initiation of early mobility and compare them. So the TEAM study was, I want to say four to five days after admission or after enrollment to the study.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 39:42

Yeah,

Kali Dayton 39:43

You had patients, usually out of bed it within 48 hours of intubation. That’s a huge contrast. And so it the way you laid it out is really powerful. So invite everyone to go to my website. Look at the transcript of this episode, look at those graphs, the way that Dr. Patel laid it out is really insightful.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 40:06

Yeah, I think, you know, for us, like, you know, it’s not even just time zero, that was unclear within a lot of the other studies. It was even like time to what? Because from my perspective, you know, time to passive range of motion is like a waste of everyone’s time.

So, you know, because in our original 2009 study (3), that’s what the usual care arm got, they got passive range of motion, and they had no benefit from it. And so, from my perspective, and you know, it’s not, it’s just based on my experience, because there hasn’t been steady sort of comparing, like time to what I guess. But for me, it’s like time to sitting.

That’s when someone took the effort to sit somebody up. And that I feel is different than a bed mobility exercise, which you can’t know for sure is like, using any muscle activation at all? And also, if, you know, when you think about, think about what’s the minimum dose, you have to think about what’s the effect I want to see.

And if the effect is, you know, no, contractures, then fine in bed mobility, I think to maintain joint fluidity, I think is fine. But for us, you know, the the awakening of the mind really happened when you had an upright positioning. And so for me, if if the main outcome you’re looking at is cognition, then probably sitting up in bed, so that they can at least engage with the providers like eye to eye, you know, practice their ADLs.

I think that is the minimum dose from my perspective. And so that’s sort of where that slide came from was like time to sitting not not necessarily a time to a therapist coming into the room or time for passive range of motion. And so I think the interventions and studies have to be a bit more clear and more precise, you know, because some of them will say, PT, I was like, What is that like, time to pt? Like, what does that mean? Does that mean sitting, does that mean standing? Does that mean marching?

Kali Dayton 42:10

PT can come in the room, but if they’re still sedated, or they’ve been sedated, and it’s just newly off? Or they’ve been deeply sedated? It could take a few days to really have active mobility?

Dr. Bhakti Patel 42:20

Yeah, yeah.

Kali Dayton 42:21

And I believe studies also need to have very clear definitions of what sedatives were given, and what depth for how long?

Dr. Bhakti Patel 42:31

Exactly? Yeah, you know, we, in our study, we we reported that we reported how many times patients were on drips, what type of drips, benzodiazepines, propofol, etc. We also had doses because we didn’t want people to think that we just sedated the usual care group.

And that’s like, the reason for the benefit. You know, we show that there’s a equal amount of sedation on both sides. There’s no differences in the sedation. Yes, delirium was less, but like, the delirium was quite low in the usual care group, like they only spent a median, like one day within delirium.

Kali Dayton 43:09

Because we already had good sedation practices.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 43:13

yeah.

Kali Dayton 43:13

Right? As a standard. So your usual care was already ahead of most other ICUs. In Chicago University, right? Yeah, university where the Shweickert trial (3) came from. So you, I already have a large history of progressive mobility and sedation practices, this is not usual care. That’s usual in most of the ICU community, I think that has to be clearly defined too.

So nonetheless, even started at a very progressive and what most would consider a very successful group as your usual care. Your usual care is what many teams aspire to, but they’re far from. So then you took it up a notch. And you still saw a 20% improvement in cognitive function one year after discharge(1). I mean, that’s incredible.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 44:00

Yeah, I mean, I think he study shows like the value added, right? of mobility. Because like, whenever you institute a bundle, you know, the, you know, analgesia for some breathing trials, and, you know, doing them at the same time, the awakening and the breathing trials, all that.

You never know, like, what’s the potent piece? They’re all supposed to work synergistically together? For sure. But you don’t know like, what’s the value added of each individual piece? But I think the usual care arm in our study shows like, what the ADA F bundle without the E does. And then what the full bundle does for the intervention group.

And I think the difference is the cognition. And so it just depends on like, what is the priority and the culture of your ICU? I think if you center that culture around mobility, you make it early. It forces you to be honest for the other things.

It won’t let you if that’s your main priority, then you can’t sedate people forever or you know, not awaken them or think think of ideas or reasons why they can’t be de-sedated. You know, my mentor JP cress, like he did the original awakening study.

I was looking through his, you know, New England journals, like in the year 2000. So it’s like over 20 years ago, and I was looking at the exclusion criteria to awakening and it was paralysis. That’s it. Every person got awakened. And the only time that you wouldn’t, is that there was active paralysis.

Kali Dayton 45:30

So with there’s nothing in the research has been developed to dispute that. But here we are in 2023. And in many of our protocols, awakening trials are not allowed until peep less than five to less than 60%.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 45:46

Yeah, yeah. And I think it’s just, you know, we set these limits in our mind, and we don’t realize that we’re handicapping ourselves. So I think future studies really have to be careful about the criteria and their protocols, because then, you know, there, they will sentence themselves to late mobilization.

You know, I, like I’ve seen, I’m not on Twitter, but I’ve seen like screenshots of things sent said about our study, and it reaffirmed my choice to never be on Twitter. Because, you know, you know, when you when you work on something this long, and like, you’ve you painstakingly tried to make it so that everything is like above, you know, above reproach.

You see comments, and you’re just kind of it kind of hurts a little. But so, you know, I think people took our study and sort of said, you know, “The study is a recapitulation of ‘mobility versus no mobility’ and the t study shows you a ceiling effect of what mobility can can do, or can achieve that it achieved a ceiling effect.”

But but in my mind that if you look at the timing of our usual care arm, that’s the intervention arm of other clinical trials, and in fact, it’s, it’s probably sooner than the intervention trial, like arms of other clinical trials. So our study really is like, truly intended early mobility versus the mobility of other studies.

And you can see that the timing seems to be the most potent aspect of this intervention. And so it’s true to the definition of the intervention, which is that early timing, and, you know, I think, you know, that, if you look at like the time for the team study, like the time to randomization, or, you know, it’s about 60 hours.

And if you think about, you know, patients probably were intubated early in that period, so we were like two and a half days in, and then the median time to sitting was three days. So that’s about five to six days, to sitting up. And that is our usual care arm. So I don’t think that this is a trial of “therapy versus no therapy”. This is a trial of “early therapy versus what people think is therapy.”

Kali Dayton 48:13

And active progressive mobility.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 48:16

Yeah, and an engagement of the mind. And so I and I don’t like, you know, I think also the concern, that they are safety problems. You know, yes, there were like safety events, you know, in our intervention arm, I will say it was, you know, for the control patients, because it was unclear when they were going to get that therapy.

So that care coordination that was sort of essential to the intervention arm wasn’t necessarily happening for the control group. So we relied primarily on, you know, a note saying, like, “There was a safety event.” So that’s why there weren’t, you know, I think part of it is an under surveillance problem, but…

Kali Dayton 48:53

A bias,

Dr. Bhakti Patel 48:54

a bias, for sure. And also, you know, when you’re doing something to somebody is part of intervention, it’s human nature to, like, count everything, you know, count as much as possible, because you’re worried that you’re harming somebody.

So, but, you know, the, you know, the safety events are not all created equal. You know, we didn’t have anyone, you know, have an arrest, fall to the floor, or like, you know, self extubation. We didn’t have those things happen during an event. And so I think unbalanced, like, you know, when you’re most moving somebody, they’re gonna get a little tachypneic. They’re gonna get tachy.

Like, if I like when, when I rarely exercise if I exercise, I have I meet criteria to stop therapy, you know, so in terms of heart rate, and things like that. So imagine if you take someone who was cardiovascularly fit before, and then you let them wait five days of no motion, and then you make them do the most intense exercise and for 15 minutes longer than a control group?

Well, yes, of course. There’s going to be more cardiovascular events because it’s showing your cardiovascular and fitness that you allow that to happen over that time. And so if I take someone who was bed bound and lost, you know, 2% of their muscle mass every day, so at five days, that’s 10%. And then I make them do 15 more minutes of intense, highest intensity activity. I’m going to see more arrhythmias, I’m gonna see more heart rate changes,

You de-stabilize them.

Yeah. And so I, I think, you know, I don’t know, I don’t know what the appetite is for the critical care community for a mobility study. Another one, I do know that it’s really hard even now to find functionally independent people who get intubated, which honestly is a good thing, it means that we have other strategies for them, and maybe they’ll be untethered.

You know, to move and because I think having the endotracheal tube just adds that nuance of sedation, and their restraint and all that stuff. But I do think that, you know, if future trials are being planned that there should be a focus on timing of, of therapy, from intubation. And not and maybe a suggestion of what a minimum dose of therapy is.

And that’s when they actually get the intervention. And I think there should be less focus on intensity, in my opinion, because I don’t think it takes much to sit up in the bed, but I have seen the benefits of that. And so we don’t, like we don’t need them to stand. We don’t need them to walk not not every person can do that. But they can sit. And I do think that that can awaken the mind in a way that we haven’t seen before.

Kali Dayton 51:45

And we need to be fighting to preserve their baseline. So meeting them where they were, and where they are. And going from there. So if they were walking in they working in waken walking COVID unit. Most patients walked into the hospital, were walking the day, you know, before they were intubated. Even if they were on high flow, BiPAP. Beforehand, they were still walking.

So we weren’t going to stop them for walking. But COVID, you know, kind of brought in some younger patients too. Unless we took their baseline and fought to preserve that. And that’s what we can walk in ICU is. It’s not that everyone’s walking, but if they were walking before, they’d better walk out.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 52:24

Exactly, yeah. And that, you know, if their non invasive strategies aren’t working, you don’t want them in bed that time because then they’ve incurred disability up until the time they’re intubation. So I think yeah, making that. I’d like your approach that walking, ICU, keeping it moving, regardless of what respiratory support you’re on.

Kali Dayton 52:46

Absolutely. Yep. And if you hit those thresholds that holds have been absolutely hemodynamically unstable, with movement, unable to oxygenate, that’s when you hit the maybe have a requirement for sedation to stop that movement.

Otherwise, most patients are moving. And that’s sounds like that’s a lot of what you did, you didn’t go off ventilator settings. So you in your study, you’ve again proven, like Polly Bailey did in 2007 (6), the safety and feasibility of mobilizing patients on higher ventilator settings.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 53:16

Yeah,

Kali Dayton 53:16

So that’s been repeatedly debunked. And so it’s time for our community to revisit our policies or protocols, and really hold it up against the evidence or even lack of evidence. But you provided so much evidence to mobilize patients early on, even during critical illness.

I would love to see your intervention group held up against truly normal usual care group that’s been done throughout the community. A deep sedation and immobility for prolonged periods of time.

Because it sounds like your intervention group or your control group was lightly sedated and mobilized sooner than others. That would be a huge contrast, if we were to measure mortality, functional status, delirium rates, and again, long term cognitive function a year after discharge, comparing it to a truly normal group, I think we’ll just see even more profound outcomes.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 54:09

Yeah, I think it’s funny because like, when we were going through the peer review process, it felt almost like we were being accused that our usual care was poor standard of care. And so it was interesting to me to hear that because I think, I think when people talk about mobility, when they talk about sedation practices, they want to be the people who do it, you know, they want to be the ones that are champions of it.

But you know, when you get faced with the data, like, we’re not as good as we think we are, like, it’s just saying, like, oh, yeah, eat my fruits and vegetables, but like, when I look at, like, what my true diet has been in last week, you know, it doesn’t mean not have as many servings of fruits and vegetables.

So, you know, and we’re, we’re at risk of it too. I think COVID You know, the young mind is harder to control than the comorbid mind, you know. So I definitely saw patients who, you know, with astronomical sedation strategies, just and completely awake because it’s a young mind with a very healthy brainstem,

Kali Dayton 55:19

and high metabolism.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 55:20

Exactly. And so and so, you know, coming out of that, and also the staff turnover because of the burnout and the disenchantment, you know, we had to reinvest in these values, we still have to do it every day. You know, sometimes it’s a pain and it’s hard behavior change is really, really hard.

Kali Dayton 55:41

Because the team you have now is not the team that you did this study with?

Dr. Bhakti Patel 55:44

No, you know, in fact, you know, Cheryl and Amy, who were sort of the, the, the originals from the 2009, and sort of helped us with the second edit of the study. You know, Cheryl primarily works in the cardiothoracic ICU. So she mobilizes patients on like VA, and VV ECMO.

And Amy actually is working, she started her own physical therapy company, and so she’s not at the university anymore. So we, you know, they had a legacy of change people, and then had other people now are training others. And so we have new champions now. But you know, it’s a continuous process.

And a lot of the therapists who come from other places, never saw someone mobilize. And so sometimes when we, when are sort of the originals, or the champions or have vacations or you know, are assigned to different units, I feel it because the, the, the notes might show like “Patient intubated on a, like not not recommended to have therapy.”

And I was like, “Wait, no!” Yeah. And so, you know, it still happens, like we we did the study, but you know, there’s no, the institutional memory dies with the people who are part of the team. And so you have to keep fighting it, you still, we still fight it every day.

And it’s just, it’s just a matter of creating opportunities and light bulbs for people to realize that that was a win by person stood up, that was a win, and, and then they never forget it, and then they keep applying it for the next person. And so you just got to make those little victories.

Kali Dayton 57:26

Give them the chances to build up their own expertise.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 57:29

Yeah, and I got it. I mean, I, you know, there’s that fear, like, I don’t want to make a bad situation worse. So like, I don’t want to what if they get worse? Or what if this happens, what if that happens? And I guess there’s, there’s people who are scared of something that could happen and use that to kind of paralyze them? And then there’s people who are like, “Well, I’m aware of what can happen, but let’s see if it will.”

You know, and so, so, I see my role. And, you know, my colleagues role, whenever we’re trying to make this happen, is just sort of say, “Let’s see, like, how do we know it’s going to happen, let’s just try. And if it happens, then we know that we can’t do it today. But like, what’s wrong with trying?”

You know, I think trying to be careful that when we don’t do something, it actually could be harmful. And we just don’t have the benefit of seeing that harm, because it’s happening like outside of our ICU.

Kali Dayton 58:28

Thank you so much for having that kind of stewardship over this process. As I’m working with teams, I see, obviously, everyone has a different kind of culture. But a lot of times, physicians say, “I support you, thumbs up, go team, but go teach the nurses how to do this. This is a nursing thing, this is a PT thing. ”

They’re not sure what their role is, and how to guide this. And so I think you’ve really set a good example of how to be an integral part of that team, and take stewardship over it. Even you being present, saying, let’s try this gives everyone an immeasurable amount of courage and willingness to do it.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 59:05

Yeah, I think like, you know, people don’t want to, they don’t want to feel ultimately responsible, you know, for something that could happen. And I get that, especially since I’m the one requesting it, right. So.

So I tried to like, take away that sense of liability and just sort of say, like, “Put it on me, like, if you feel uncomfortable, I will be here.” And I think we as, as the physician, you know, you have to sort of you can’t leave your team hanging, like you can’t say like, “okay, good luck.”

You know, I’m not saying that, I fully admit, but it can’t happen without, you know, our therapy team, the nursing staff like respiratory therapy, so like, it just can’t happen. But my role is primarily to say like, let’s make it happen, and I will I will take responsibility for what happens. And, and let me know what I can do to make it happen.

And, and I think that it goes a long way because it is a lot of work. And it is a lot of coordination and it is risk and but if you sort of say like I want this to happen, and then don’t check up on it and are not accountable, then it’s not going to happen. You’re sort of acting like you’re like the king of the team and sort of begs laying down an edict and then hoping that everyone else will follow your orders, I just don’t think the ICU can work like that. It doesn’t work that way.

Kali Dayton 1:00:39

I see physicians having leadership, some stewardship, accountability, support, and part of that countability is looking at the data. So not just assuming that it’s been done, but looking at what are we doing as a whole?

So you bring up a strong point that those reviewing your study, were scoffing at your usual care group, but likely their own teams, were not up to par either. And that’s what I’m finding when I as a consultant, when I go in and ask people for their data. Even I present their data, sometimes they get very defensive. And that’s never my intention is to put anyone on guard.

But it’s not until we see that in the data that we realize where we’re at, or to go and compare what the real RASS happening at the bedside is compared to the prescribed RASS. Until they see that. It’s easy to say “We’re doing that we’re doing the A to F bundle, it’s fine. Our patients are mostly mobilized. It’s okay.”

One team said that when I went on site, do a gap analysis, the medical director said, “Our sedation practices are fine.” Hours later, I watched a patient be intubated for benzodiazepine use for two weeks. So it’s not until you really have maybe an objective party, new eyes, or just looking at the data yourself, that you see where you’re at.

And physicians have a huge role to play in this. Maybe they’re not the ones bringing in the socks all the time. But they do need to make sure that the team fully feels and even sees their support, and that there’s follow up and there’s expectations and education.

For a physician physician to say, “If we keep sedating this patient today, this patient for every one day of sedation, or delirium, there’s a 10% increased risk of death.” I think a physician saying that in rounds, changes the tone of the whole discussion. This is not just a nursing, this is not just on PT, this isn’t everyone problem and project. But it’s feasible! You’ve proven that in your study. It is absolutely safe, feasible and beneficial.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 1:02:40

Yeah, I think it’s, I think now the job. And the hardest part is to figure out how to make it work in everyone’s different settings, right? You know, every unit has a different culture. Every unit has a different level of acuity, and the cohesiveness of the team.

And so figuring out how to make that cohesion happen, is I think, the massive sort of effort that everyone needs to make. And, you know, it’s funny, because it’s sort of like, I sort of always tell the team, I was like, when we think about major interventions in critical care that had the most therapeutic benefit.

They’re ones that draw providers in the room, and, and put in resources, they’ve never really been a machine going into a room necessarily. So think about proning you know, people have to go in the room and turn the patient and there’s a, you know, 12% mortality benefit. Think about turning down the tidal volume, someone has to go in the room and do that and be okay with like, the gas exchange being worse, but they’ll patient will survive more.

You know, now it’s like mobility. And, and so, you know, nothing worth having is ever easy. And I think like, I understand the cost, and people will talk about people are expensive. But you know, if we think about the disability, people incur the, yeah, we’re kicking the cost to somebody else, we don’t see it. And it’s not even, you know, accounting for the human cost of, of losing, like you survived, but you’re like, not yourself, and you’re not part of society anymore.

And you’re just sort of in this island alone. I don’t know, i None of us, I think who work in the ICU like, find meaning in that? I think, you know, for us, like we I really try to humanize the person and the only way to do that is to wake them up and see them move.

And it’s harder, and it’s really painful to like, get people to believe but you have to keep fighting otherwise there’ll be this like slippery slope of you know, just to be safe just to be safe. And that culture of like oh, Just wait, you know, let’s just be safe. You’re missing out on like the true harm that’s happening.

They’re actually like literally dying in bed and you don’t, you just can’t see it. And I think that’s the part that kind of motivates me, but it is, it is a grind. It is something that is going to because it coordinates people coordinates behavior, you have to change minds perspectives, you have to get, you know, people to invest in the resources.

But, you know, I do think that it will pay off for patients and what why do we why do we do this? Like, what why do we do this ICU care, like we want people to, to live but also be themselves? And we also don’t have an alternative? Like, what’s the alternative? You know, there’s been no other interventions that we talk about.

Post ICU recovery, we talked about long COVID We talk about all the disability after critical illness, and everyone loves talking about it, measuring it, you know, describing how prevalent it is. And, and always a footnote is maybe we shouldn’t localize, you know, but it’s just like,

Kali Dayton 1:06:09

We have the solution!

Dr. Bhakti Patel 1:06:12

And but then it’s like, “Oh, you know, I don’t know that it works as data’s like, conflicting. We shouldn’t do it.”

I’m kind of I’m kind of over explaining it. Like, I know how bad we are, like, I know how bad we make patient’s recovery look like. And I’m just kind of tired of feeling bad about myself about it.

And I just, let’s just do something and maybe maybe in like the everyone’s hands, it’s not the same benefit as within a trial, but like, what else do we have? And and, you know, I think based on like, our safety profile of the timing of our intervention, like, I don’t think that there is excess harm, as has been suggested, you know, that there’s no difference in one year mortality.

You know, I do think that there is potentially harmed by waiting and then trying to push them to do more than they can. But why wait? I think we we’ve shown that you can, you don’t have to wait. There are criteria for safety, but you don’t have to wait as often as you think.

Kali Dayton 1:07:23

You don’t have to wait four to six days, right?

Dr. Bhakti Patel 1:07:26

Yeah. And I, you know, I’ll also like, you know, our patients had a high severity of illness. They were higher than the other trials. So we were doing it in really sick patients.

And so, you know, the number one question I get when we talk about the studies, like, “How do you make that happen?” And it’s sort of like, we, you know, I don’t know what to say to that other than “Patients were in our study, and we had criteria and they met criteria to move and so we moved them”.

Kali Dayton 1:07:52

You had an open criteria, which helped you do it sooner, which helped it be safer, which helped to be more beneficial and helped to be easier. Yeah, it’s hard for people to imagine when they have these really restricted criterias. And they’re only doing on the very, very end of an ICU stay. That is very difficult and really hard to imagine patients actually being awake and walking.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 1:08:15

Yeah, I think, you know, it’s a credit to like my mentors, like they they built our ICU like the laboratory. So they, they sort of are always thinking about how to break apart paradigm. So between like Jesse Hall and JP Cress.

I think the thing that gets my mentor, JP going is sort of like, when someone says he can’t do something, you know, I think for him, he’s like, “but why?” And if there’s no evidence for why then he’s like, “Well, what if we just did it?”

You know, and I think having that sort of a little bit of a maverick kind of mind frame, I think is a way to question like, what we do is standard of care in the ICU, because it’s hard to know like, what what is all of this like? That what we’re seeing? Is it because of what we’re doing? Or is it because of the illness?

And I think our philosophy has always been “less is more”. It’s been borne out over and over again, no, ask any question of what you do in the ICU, it’s sort of like less is more. And it’s humbling, because it’s sort of like, the more I tried to do something, the more harm I’m causing my patient.

But in the end, it’s sort of like less is more that the body can heal itself, we have to get out of its way. The mind will recover it, we just have to not cloud it with sedative. You know, the patient can breathe, we have to support them. We don’t have to control every breath. Like it’s sort of those things like thinking about it that way.

Sure, there’ll be patients who are on the extremes that, you know, I’m not saying that this is a solution for every problem. But I think it’s not a rare enough indication that we think it is and that we should actually shift our culture to really make sure that mobility and function and thriving after the ICU is paramount.

When we make our clinical choices to see like, does it have the therapeutic value that we thought it had? Or is it really just harmful?

Kali Dayton 1:10:08

Dr. Patel, thank you so much for everything you’ve done for the community, your your study really is going to make an impact. I invite everyone to look at the transcript to see the graphs that we’re sharing to look at the citations that will be mentioned, and really understand what we’re talking about. Thank you so much for everything you’re doing. And I’m excited for the future.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 1:10:28

Thank you so much for having me. It was great. A great conversation.

Kali Dayton 1:10:32

It’s cathartic, right? Just put it out there.

Dr. Bhakti Patel 1:10:34

Yep.

Kali Dayton 1:10:34

Thank you so much.

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

References

1. Patel, B. K., Wolfe, K. S., Patel, S. B., Dugan, K. C., Esbrook, C. L., Pawlik, A. J., Stulberg, M., Kemple, C., Teele, M., Zeleny, E., Hedeker, D., Pohlman, A. S., Arora, V. M., Hall, J. B., & Kress, J. P. (2023). Effect of early mobilisation on long-term cognitive impairment in critical illness in the USA: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine, 11(6), 563–572.

2. https://www.thebottomline.org.uk/summaries/icm/rose/

3. Schweickert, W. D., Pohlman, M. C., Pohlman, A. S., Nigos, C., Pawlik, A. J., Esbrook, C. L., Spears, L., Miller, M., Franczyk, M., Deprizio, D., Schmidt, G. A., Bowman, A., Barr, R., McCallister, K. E., Hall, J. B., & Kress, J. P. (2009). Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England), 373(9678), 1874–1882.

4. B. TEAM Study Investigators and the ANZICS Clinical Trials Group, Hodgson, C. L., Bailey, M., Bellomo, R., Brickell, K., Broadley, T., Buhr, H., Gabbe, B. J., Gould, D. W., Harrold, M., Higgins, A. M., Hurford, S., Iwashyna, T. J., Serpa Neto, A., Nichol, A. D., Presneill, J. J., Schaller, S. J., Sivasuthan, J., Tipping, C. J., Webb, S., … Young, P. J. (2022). Early Active Mobilization during Mechanical Ventilation in the ICU. The New England journal of medicine, 387(19), 1747–1758.

5. Kress, et al. (2000). Dailiy interruption of sedative infusions in criticall ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. New England Journal of Medicine, 342.

6. Bailey, et al. (2007). Early activity is feasible and safe in respiratory failure patients. Critical Care Medicine, 35(1), 149-145. Retrieved from

7. Graph “Timing is everything…“:

SUBSCRIBE TO THE PODCAST