SUBSCRIBE TO THE PODCAST

The ICU community is buzzing with talk about the recent NEJM “TEAM Study”. What do the methods and findings of the study tell us? The author of the study, Dr. Carol Hodgson as well as Dr. Wes Ely and Heidi Engel, DPT join us to dissect and discuss this study.

Episode Transcription

Kali Dayton 0:02

Okay, everyone, thank you so much for coming on the podcast. Let’s introduce ourselves starting with Dr. Hodgson.

Dr. Carol Hodgson 0:10

Hi, my name is Carol Hudson. I am Professor of Intensive Care Research at the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Research Center in Monash University Australia, and the lead investigator for the team trial, which was just published in the New England in October this year.

Kali Dayton 0:26

Excellent. Thank you so much for being willing to discuss your research with us. And Dr. Ely?

Dr. Wes Ely 0:32

Hi, my name is Dr. Wes Ely. I’m an intensivist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, and really thankful to be here with all of you tonight.

Kali Dayton 0:40

And Heidi Engel.

Heidi Engel 0:42

Hi, I’m Heidi angle. I’m a physical therapist working in intensive care unit and have for many years at UCSF Medical Center in San Francisco, and trying to do some research and teaching related to all of that as well.

Kali Dayton 0:58

Excellent. So Dr. Hodgson, tell us about the this new team study that has the early mobility community chatting and discussing.

Dr. Carol Hodgson 1:08

Yeah, sure. So I think it’s important to say that this was a long program of research. The study didn’t start, you know, five years ago, when we actually started doing our big phase three trial. This is something that we’ve been working on for over a decade. And within our clinical trials group, we do a very thorough program of research. So our program of research has included a bi national observational study to define what was standard practice, a pilot, randomized controlled trial to test the intervention and to test feasibility and systematic review to update both the outcome measures and the endpoints that we wanted to test in the trial. And to make sure that we were right up to date with the most current evidence.

And then finally grant application for our phase three trial. And I think that the background behind this is that we know that ICU acquired weaknesses common, it occurs in about 40% of critically ill patients, we know that ICU acquired weakness is more than just a result of bed rest, we know that it’s a result of critical illness causing cytokine production, which results in microvascular changes and metabolic derangements and increased protein catabolism and changes in the actual muscle structure. We believe that there’s potential for early mobilization to mitigate ICU acquired weakness, we know that the ICU acquired weakness occurs really early and the you know, the lovely work that was performed by Bushwhacker. And his team in their study that was published in The Lancet in 2009 (1) led us to believe that early mobilization, if it was started very early in this day, and performed quite proactively may mitigate the effects of ICU acquired weakness compared with standard care.

So all of those things led us to conduct the team trial where we aimed to determine whether early activity and mobilization in the intensive care unit would increase the number of days alive and out of hospital to day, 180. So we hypothesized that early active mobilization would increase the number of days live and out of hospital. And so this was an international multicenter prospective parallel group randomized controlled trial, we conducted it across 49 centers. 28 in Australia, five in New Zealand, eight in the UK, four in Ireland, three in Germany, and one in Brazil, we included patients who were intubated and mechanically ventilated, for at least, you know, expected to be ventilated the day after tomorrow. And they had to have sufficient cardiac and respiratory stability so that they could participate in the intervention or potentially participate in the intervention.

And we excluded anybody who we thought wouldn’t survive to day 180, or who was dependent in their activities of daily living in the day prior, or who had impairments such that I wouldn’t be able to perform the early mobilization. And those included cognitive impairments, or proven primary brain or spinal cord injuries or rest in bed orders. So we followed this protocol where we tried to get patients to perform active mobilization as early as possible and at the highest level possible.

So for example, if they could move their arms and legs against gravity, then we would try and sit them over the edge of the bed and move their trunk and their head against gravity. And if they were able to sit over the bed, we would immediately assess to see if they were capable of standing. So we tried to progress through their levels of mobilization quite quickly, and usual care. And we did this with interdisciplinary discussion using a safety checklist, minimizing sedation so that the patients at least for the time that we were performing the early mobilization intervention were had their sedation minimized, and we used senior physiotherapist at the side. And that was compared to usual care where usual care was

As usual care mobilization and rehabilitation, and it was delivered by staff who were not involved in the intervention when whenever that was feasible. And as you know, because you’ve probably read the study, you know, we had a published statistical analysis plan, we plan to randomize 750 patients, which we did, we had great recruitment across the site. So this was a study, despite the pandemic, it was delivered on time and on budget. And we had less than we had 99.6% follow up for our primary outcome, which, you know, was fantastic, I think, considering the number of sites that we had involved. And we had very minimal differences at baseline between our two groups.

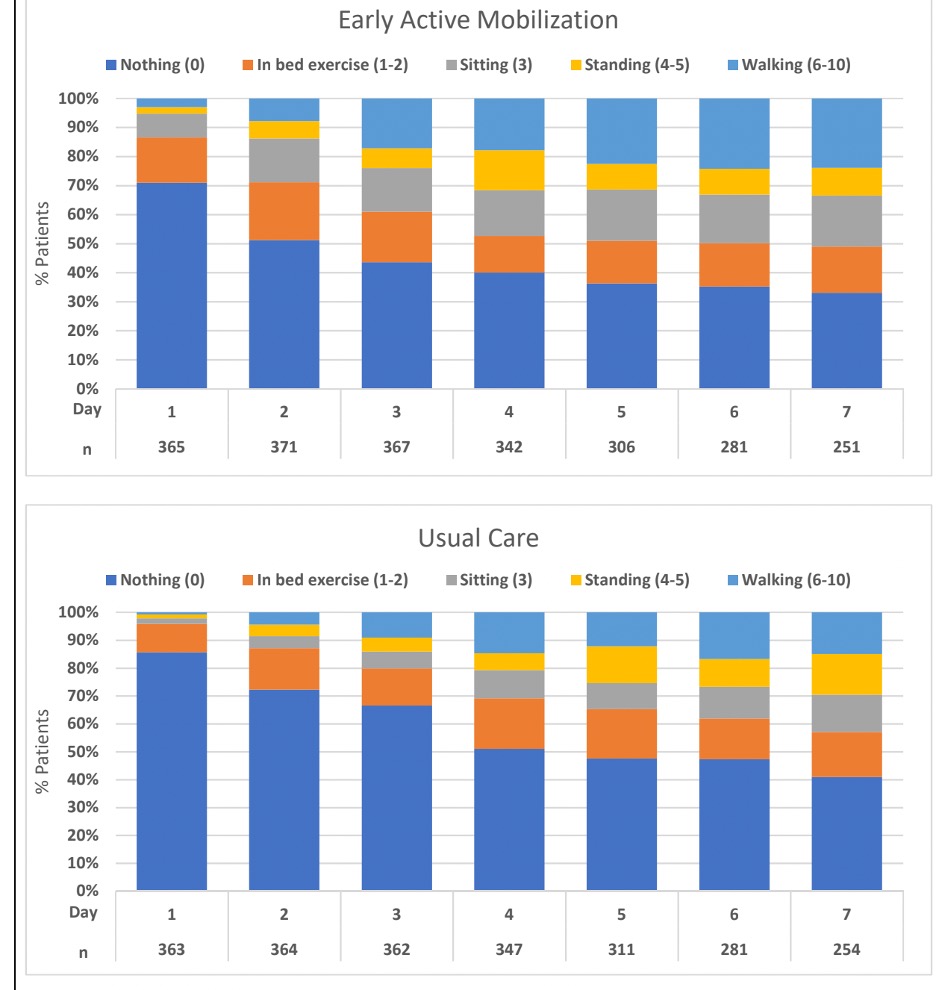

And yet, we found no difference in the primary outcome. We were able to deliver double the number of minutes of mobilization, although it wasn’t a huge difference, it was 20 minutes versus eight, but it was more than double the number of minutes of mobilization. And the number of patients who were assessed on a daily basis was more in the intervention group. And the levels of mobilization were achieved earlier in the intervention group. So there was separation between the group although perhaps not as much as we had expected, because the usual care received a really good standard of early mobilization, I think, compared to other centers around the world.

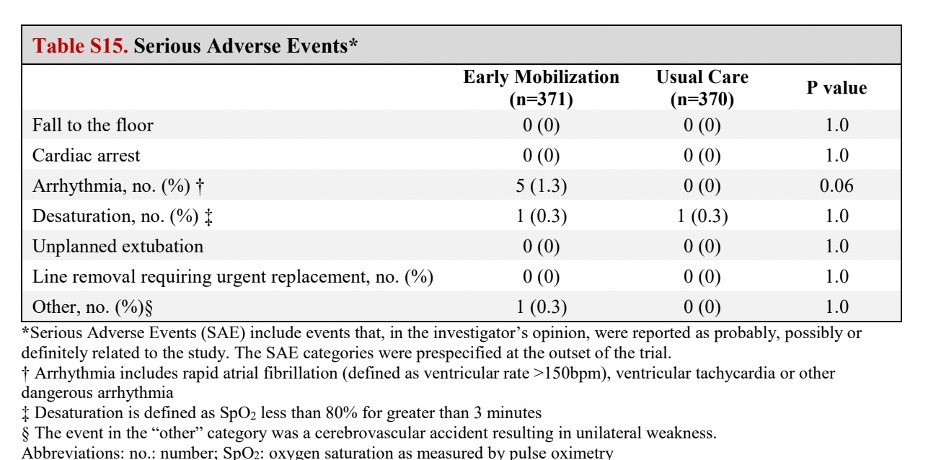

So there was no difference in the primary outcome, there was no difference in survival by treatment group, there was no difference in any of our secondary outcomes, including our functional outcomes to the day 180. So that was cognitive function, psychological function, disability, anxiety and depression or screening for post traumatic stress, we did have more than doubled the number of adverse events that occurred in our intervention group compared to our control group. So there’s been some concern with the signal for harm. Not only did we have an increased number of adverse events, but we had more patients in that group who had more than one adverse event. So they had multiple adverse events.

And in terms of serious adverse events, we had seven in the early mobilization group and one in the usual care group. And they were mostly series everything is so ventricular tachycardia, mostly, one patient had a significant prolonged desaturation, that needed intervention. And one patient had left sided weakness after early mobilization. And we think that that patient probably had a stroke as a result of a DVT or a PE. So overall, we found no difference for very early active mobilization compared to usual care where usual care was a very good standard of mobilization, but as a signal for increased adverse events.

Kali Dayton 7:44

Well, thank you so much for all of your incredible work on this project. These are important things to study and to evaluate. I know that Heidi and Dr. Ely have some questions about some of the methodology and some things that I think there are a lot of things that we can learn from the study, even beyond just the conclusion that we’ve received. Heidi, Dr. Ely, you want to jump in?

Dr. Wes Ely 8:09

Go ahead, Heidi.

Heidi Engel 8:10

Well, I would jump in with saying I think this is an amazing study. And I think there’s a lot for us to take away and learn from it. And I don’t think it’s necessarily a negative study. So I think a lot of folks in the physical therapy community that works in the ICU have have taken it with alarm, and have thought about it as something that’s very, very negative about the work we do every day when we go into the ICU to mobilize patients. And what I took away from this study, as someone who’s you know, spent day after day mobilizing patients in the ICU for in 15 years.

I took away from it really that we aren’t there yet. And Kali, I want you to speak to what their looks like because what I saw in this study is what I think I see in ICU practice for early mobility in multiple ICUs. And that is that we have patients sedated even on low level light sedation and we will turn it off for the mobility session and then we will do what we can with the patient in that state. And then at some point the patient will get back in bed and be the sedation will ultimately be put back on again especially at nighttime.

Dr. Wes Ely 9:34

Thanks so much, Heidi. And Carol, appreciate you and Kali, thank you for having us on today to have this conversation. I think that, first of all, to frame our lives as academicians. And as clinicians, we have to remember that every time we ask a good question, and get data back, it’s a time to learn. And when we get data from a study that was as comprehensive and thoughtfully designed Carol, as the Hodgson trial, the this is, this is a time for us to sit back and reflect on what did we learn? And how do we move forward? And I think that more and more in my life as a graying intensivist. I think that Heidi hit the nail on the head that this is really all about an error in our thinking with regard to how to best care for the human being who is critically ill in the ICU. And the error all began back in the 90s. When we thought Let’s spare them memory, Let’s spare them awareness. And let’s do what we think is paternalistically the most humane thing to do for them, which is to deeply sedate them and keep them in an immobilized state.

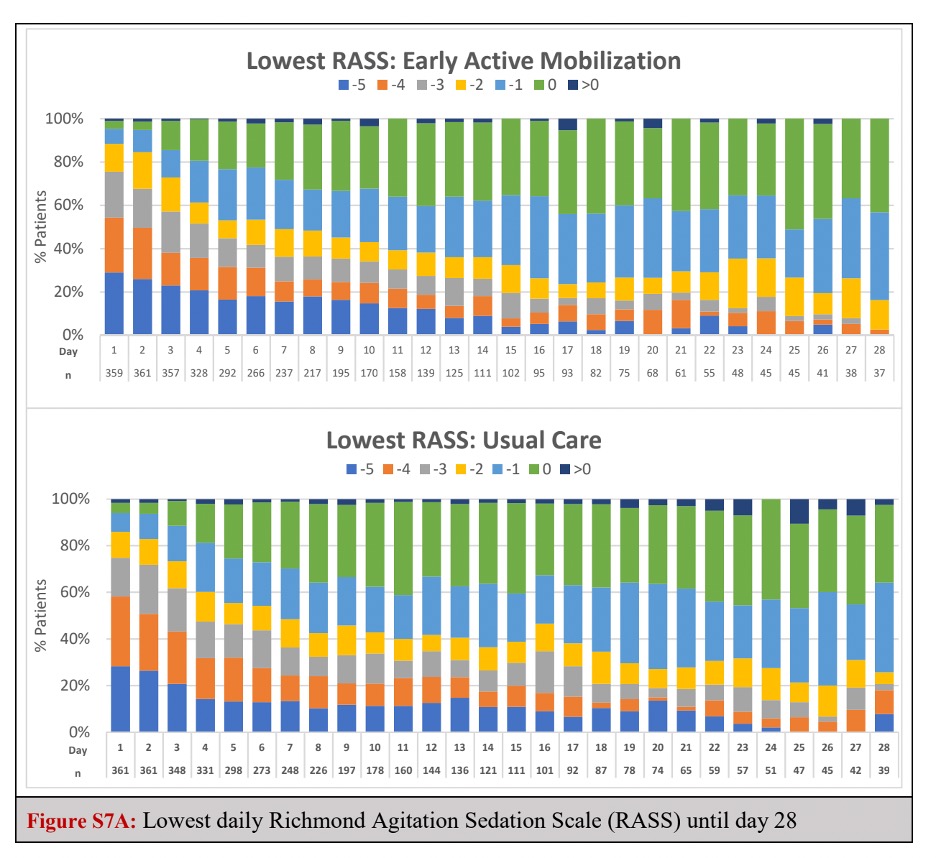

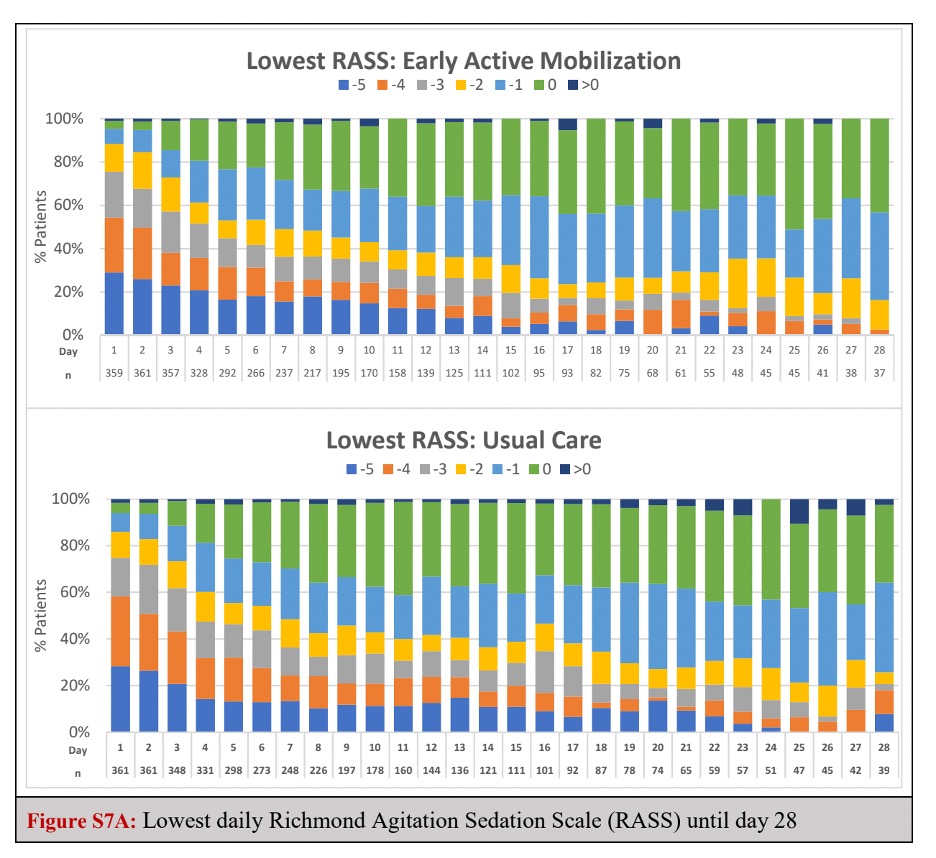

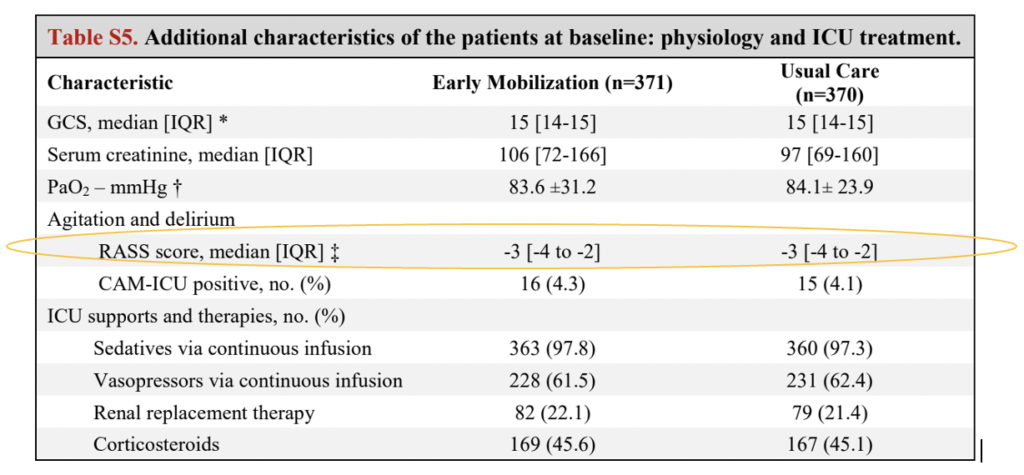

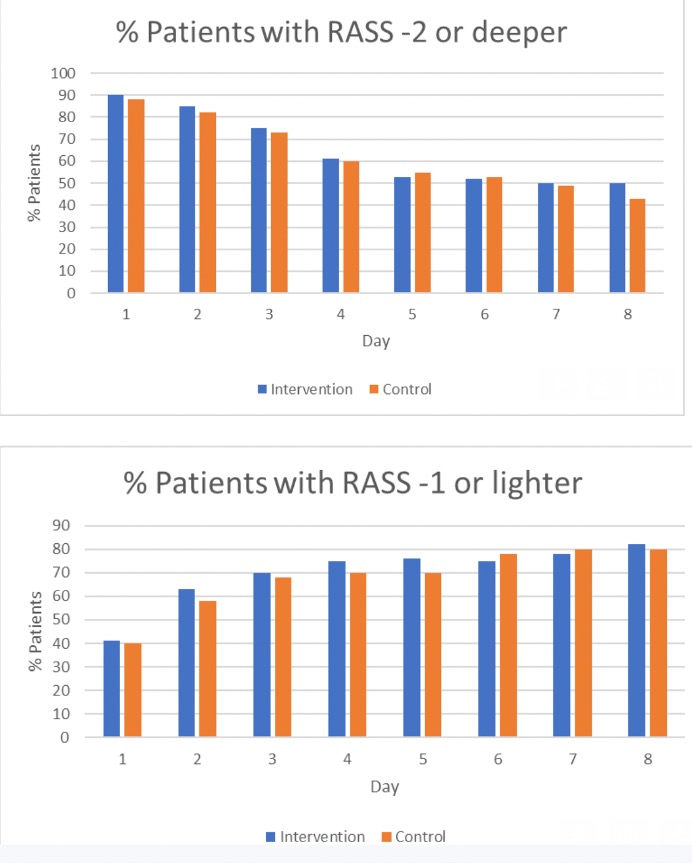

I know that this intervention was designed to have people mobilized early, and yet the data in the main paper in the appendix could show that despite these best efforts, 70% of the patients were at RASS -2 or greater for the first 72 hours after enrollment, and RASS minus two what is that that means that you cannot make sustained eye contact.

That means that something about the way your brain is working, won’t continue to pay attention. Remember that delirium is best predicted by the ability to pay attention. And so when somebody is unable to make sustained eye contact, they are manifesting phenotypically in attention. And that is somebody who has a difficult time following the commands of mobilization.

So when Polly Bailey, one of the pioneers in early mobility was asked by Roy Brower to come to Johns Hopkins, so that the people at Johns Hopkins could understand how can they get better at this world renowned medical center? Roy to the first patients that Polly what do we do next? And Polly said, “Well, in this patient, I would lighten sedation.” And in the second patient, Roy said, “What would you do now?” And she said, “Well, I’d lighten sedation.” And the story kept going in that in that way. If you I’m gonna give you a few more data points.

If you look back at the Schweickert paper (1), and then three other major randomized trials, which were published in 2016, Schweiker was 2009. And then Moss and Morris and Schaller. Were all in 2016. The real contrasting data that that was telling in those four clinical trials was that if you got actually mobilized in the first one and a half to two days, which happened in Schaller(3), and Schweickert, we saw definite improvements and ADLs and independence and reduction, two to three day reductions in delirium, and also ventilator improvement management, ICU hospitalization duration, as compared in contrast to mark moss and Morris, where the the true actualization of mobilization was three to eight days later.

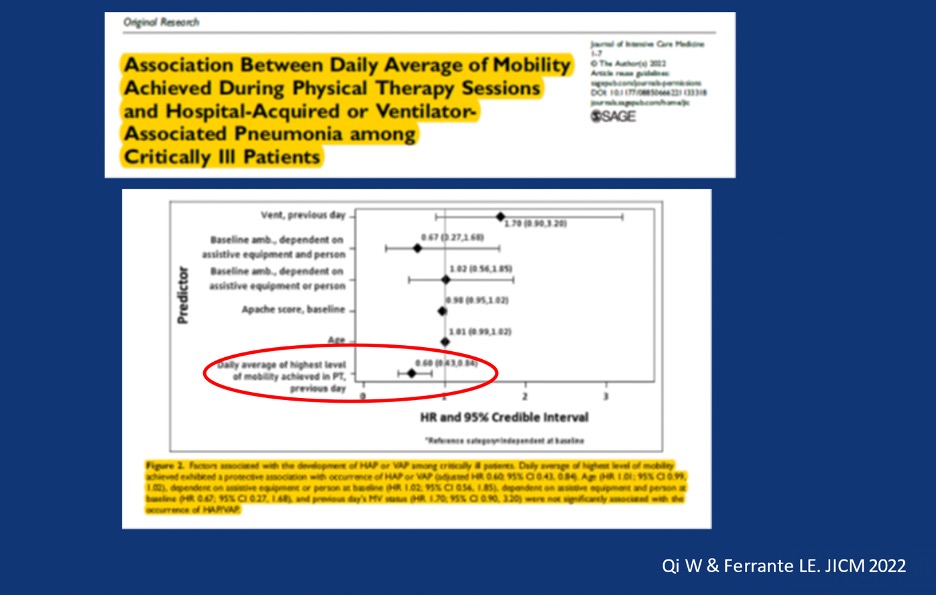

So it was basically two studies early. Two studies late early mobilization actually reduced bad outcomes and improve lots of things that were barometers of primary and secondary outcomes. We have two recent data by the way from Lauren Ferrante(4) which which showed that in terms of ventilator social had pneumonia 40% reductions in ventilator associated pneumonia with early mobilization.

And the largest meta analysis of all was by Peter Nydahl(5). And it was 22 studies, many, many 1000s of patients, and saw reductions in in delirium and hospital length of stay as well with early mobilization. So, in summary, my take would be when we get a culture that allows people to be RASS zero to minus one within 24 to 48 hours, which, which wasn’t achieved in this investigation, apparently, by the data showed, we can get people up and mobilized and it will make a difference when we overstate them and we’re all guilty. When I point a finger, I’m pointing three back at me. So I am complicit here, absolutely complicit, that when we don’t treat patients with, with actual light sedation, saying that we’re doing like sessional paper is not actually doing like sedation. When we do it, right. Patients get better and the improvements are there, those are my thoughts.

Dr. Carol Hodgson 15:21

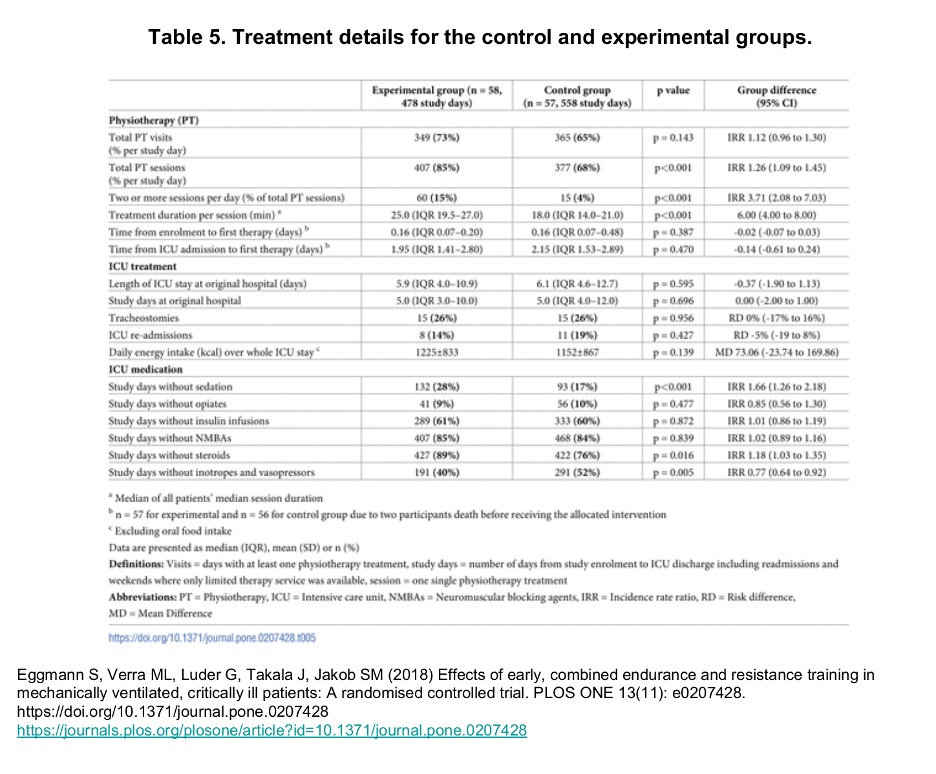

So a couple of points to respond to both of you. And I really appreciate your comments and take them on board. And as you know, I’m a huge advocate for early mobilization. And my background is also physiotherapy. And it’s what I’ve spent the past 30 years of my career trying to advocate for. For starters, when we speak about eight minutes of active exercise in the control group, compared to 22, in the intervention group, Heidi, I just wanted to clarify that that doesn’t include any of passive movements, or sitting in a chair or sitting up in bed, it doesn’t include any of the preparation time or the planning or the pickup time.

So that is purely eight minutes of actual active exercise that the patient is participating in, as opposed to, you know what you might do. And even if they were moved to sitting out a bed into a chair, once they were sitting out of bed, that that time wasn’t accounted for in that because we were no longer actually doing exercises with them, they were just sitting. So just to clarify that I think that people look at that eight minutes, and they think that’s a really low number.

In fact, if you add the physios time, by the time they assess the patient and strengthen, set up the bed area and do the intervention and pack up the bed area, and maybe leave them sitting out of bed, it is much closer to an hour that you would need to perform those eight minutes a very serious active exercise. But I do acknowledge that that sounds like a small number. But for those of us who actually do it, I think you would understand if it doesn’t include the setup and pack up, it’s a bit different.

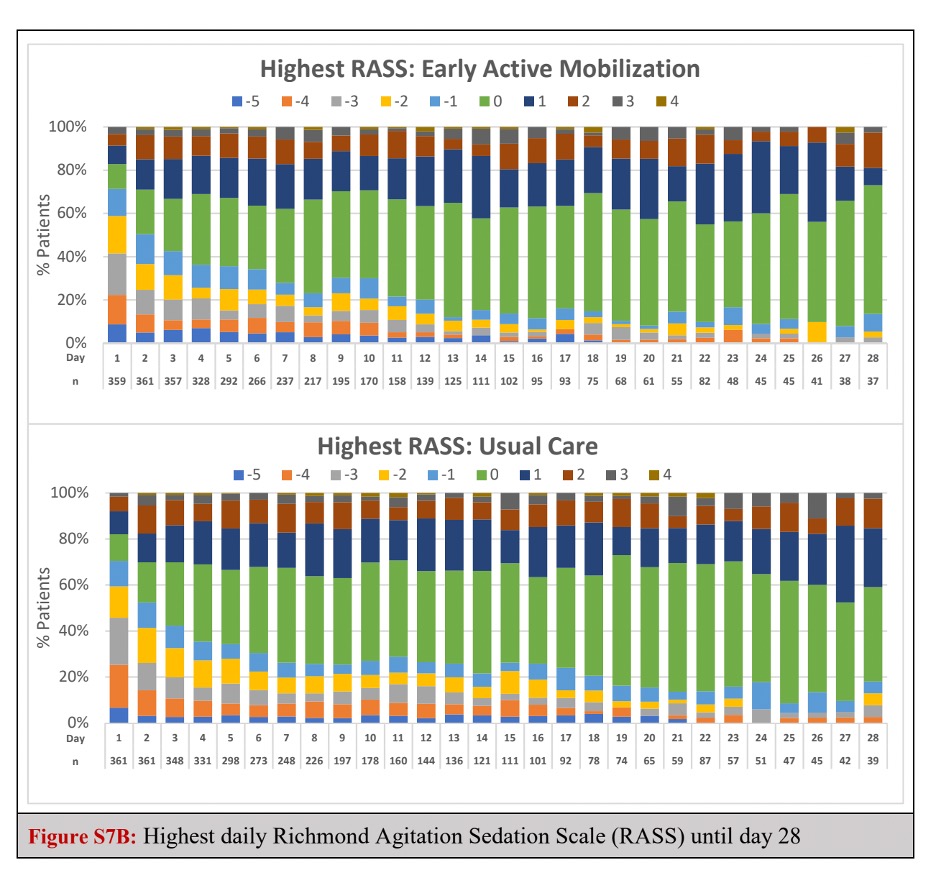

And Wes, I really like your comments about the rest, I’m worried though, that you’ve been looking at the lowest rest table rather than the highest stress table. So we asked that our patients and Heidi sort of alluded to this, that, you know, we weren’t asking that we were allowed to de-sedate the patients to allow mobilization to occur. So in fact, we had 66% of patients who achieved a RASS of minus two to plus one within the first within the first 48 hours. And nearly 80%, 79%, within the first three days achieved a RASS of minus two to plus one. And we had a huge number of patients over 80% of patients who mobilize within the first three days.

So we did achieve mobilization and we did achieve a light sedation for the mobilization to occur. But that doesn’t mean that light sedation, it means that during the day that patients had a range of sedation scores, where the lightest one allowed mobilization in the heart and the lowest one meant that they were probably back being sedated as you say Heidi potentially overnight, potentially at other times during the day. And of course, we would all prefer the aim to be that we have our patients quite awake.

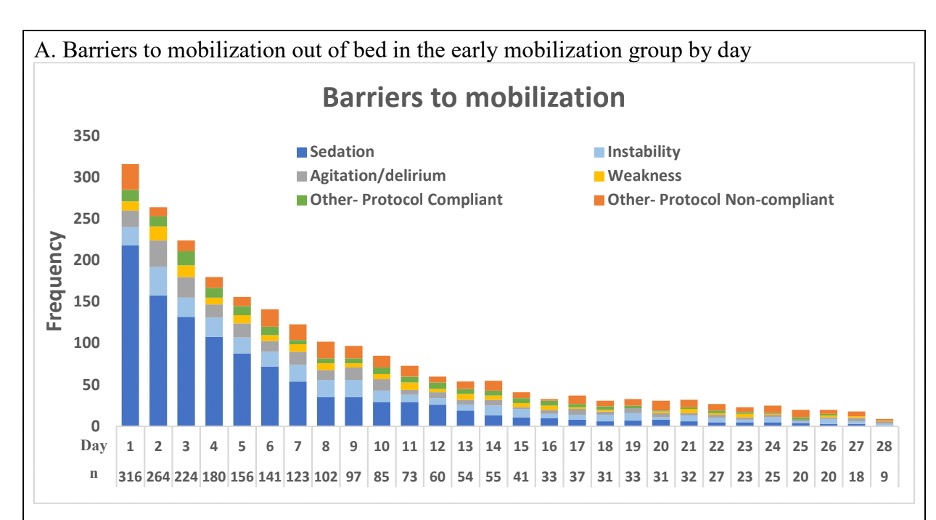

But there were some good reasons I think why our patients weren’t and we actually listed the barriers to mobilization as as you saw where sedation was the largest barrier, in the opinion of the physiotherapist who were trying to mobilize the patients. But there were other reasons good reasons why patients couldn’t be mobilized, including, you know, neurological problems and instability and other reasons why they weren’t able to be mobilized.

Dr. Wes Ely 19:13

That’s a good point about the lowest versus the highest RASS. What I’m thinking of though, Carol, is when 70% are at a minus two or deeper on any given day, I’m just thinking as a clinician caring for these people that you know, that’s, that’s minus two is the highest and that in that situation, I mean, meaning that minus two or deeper means it could have been minus three minus four minus five in that deepest table.

Now I know that later on in the day, by the by the highest stress, they’re lightened up the drug is lightened to a degree that they are perhaps higher in some circumstances, but yet that stuff that grogginess goes on and that overall perception of where is this patient in their recovery status is so jaded. In Me, as I’m looking at them thinking, “Well, God, they were just in a coma. Now they’re not.”

There’s something about, I’d love to ask Heidi, this. There’s something about seeing somebody’s awake and staying awake. That sends me the message. This person is ready for mobilization as opposed to coma, coma, coma, awake for 15 minutes. Oh, we’re at we’re now ready. No, I’m still thinking. We’re not far enough out from sedation yet to do this safely. And I’m going to be hesitant. I’m going to be reticent. And I’m going to be, you know, thinking this person cannot quite go through a full, let’s walk you down the hall on a ventilator? How do you can you comment about your real world experience in this regard regarding how how long they are unsedated?

Heidi Engel 20:48

Yeah, I feel like so the message of this Society of Critical Care Medicine ICU liberation campaign had been light sedation and lightening sedation, and particularly post COVID, we did get used to tolerating a lot of sedation in patients routinely over long periods of time. And I do find that that many practitioners want to turn the sedation off, because that is what the A to F protocol says. But then they walk away from the bedside. And often it is a measure of safety, often as a measure of, “Well, I can’t be watching this person all the time, often as a sense that sedation is a form of rest. Once the patient has gotten up moved a little bit, the standard practice is to turn the sedation back on, or so.” And it’s it really is looked at as a compassionate, comforting rest. It’s as if we’re giving someone you know, a nice “nap” is the way that the providers, I think, view the sedation.

And I think what it does actually is create in the big picture and the long term, greater problems than it actually solves. I think I think Intermountain Health has created a standard of treating patients and sedation, sedating them procedurally, in a way that allows the patient to be coherent enough to get up and walk down the hall on a regular basis. So in my dream world, yes, I think one of the things this study tells us the team trial is, you know, because we will do this on off sedation, very easy, turn the sedation back on are very easy delivery of sedation, there’s a low bar for what does it take to get us to sedate a patient, they don’t have to be decompensating, in order for us to sedate them, again, because what I see is providers think we’re doing something compassionate, you know, like, I can’t get a good night’s sleep, and you’re giving me a little something to help me sleep and rest more.

So because we have a very low threshold for turning sedation on, I think we don’t understand how we are creating patients whose highest levels of mobility, like we see in the TEAM trial, are maybe getting to a chair after a week in the ICU. We don’t have patients walking down the hall because they’re not awake long enough throughout the day, and they’re not awake period enough to go through the coordination of standing up, getting the equipment together and safely getting down the hall. My patients who have this on our sedation strategy, and it’s a lot of them, usually can’t walk and they can’t walk because the residual impact of the sedation doesn’t allow them like you said, the engagement, the awareness, the coordination, they can’t do it, I can get them to a chair, I can get them on the edge of the bed, I can sit and do exercises with them.

But they also exhaust very quickly and I think we haven’t drilled down enough into looking at the risk benefit analysis of our sedation strategies and I think the team trial really tells us it’s time to go back and address cumulative doses of sedation right? We’re turning drips on and off like the it’s accumulating in in folks tissues and and I think this study demonstrates a lot of well of course we want to mobilize folks but we’re trying to we’re trying to have our cake and eat it too in a way right we want to sedate them and we want to mobilize them and it’s not working is to me what the team trial tells me and

Dr. Carol Hodgson 24:57

Just to correct you, Heidi, we were able to stand patients by day three. So in the intervention group patients stood by day three.

Heidi Engel 25:04

Not the majority of them. It didn’t seem like that on the table…

Dr. Carol Hodgson 25:08

On average, they stood at day three.

Kali Dayton 25:11

And I had read that only 6.9% more patients in the trial group were walking versus the control group. Is that true?

Dr. Carol Hodgson 25:20

Right. That’s by the end of the ICU stay, though. So it happened earlier in the intervention group, but by what we were saying is by ICU discharge, what was the highest level of mobilization and they had achieved a very similar level of mobilization by the time they were ready to be discharged from the ICU.

Kali Dayton 25:38

Interestingly, a lot of this resonates with my experiences in an “Awake and Walking ICU”. Dr. Ely brought up Polly Bailey (6), she is my mentor, I started working with her at the very beginning of my career as a nurse leader, nurse practitioner. And in that ICU, it’s standard practice to allow almost every patient to wake up right after intubation. sedation is not automatically hung, they are a RASS of zero. It’s customized per patient. But when this trial shows that there were so many adverse events, it makes me wonder how much of that had to do with delirium.

I did an episode a little bit ago on unplanned extubation. A lot of agitation happens from delirium. But those are the exception in this awakened walking ICU because delirium is so low, the rates of delirium are so low. So when I saw that the barriers were sedation and agitation, they seem to be almost the same thing. They were either had hypoactive delirium, from sedation or hyperactive delirium from sedation. And those are very difficult. And when I work with teams, to help them improve their mobility practices, the teams that I see with the most success are those that adapt the “Polly Bailey Method” of allowing patients to wake up right after intubation. And they ask after each intubation: Does this patient have an indication for sedation? And if not, then they’re not sedated. And it’s incredible to see how many more mobility sessions happen, how the level of mobility progresses so much quicker with these patients when they’re not sedated. And so I thought I found a lot of validation in the TEAM study with that.

Dr. Carol Hodgson 27:13

And the breakdown of the groups of adverse events that were related to mobilization, were more about oxygen saturation, and cardiac arrhythmia. That was by far the most common, some altered blood pressure as well, although that happened in both groups more than the ill the early mobilization group. And there was four patients in the early mobilization group only, and one in the usual care group who had issues around pain and agitation. So I think it really was more related to the intervention itself, rather than delirium per se button. You know, there you go, just mostly oxygen saturation and cardiac arrhythmias.

Kali Dayton 27:50

And overall, what was the percentage of adverse events during all the mobility sessions?

Dr. Carol Hodgson 27:55

Yeah, it was low. So I, let me just have a look. Sorry, I’m not sure if I’ve got the exact percent in front of me, but I mean, it’s, it’s a relatively low number per patient. You know, it still is a low number. But I guess, when you have more than doubled the odds in the intervention group, compared to the control group, that’s I think, what is important for people to know is that, you know, not only did we not gain anything, in fact, you know, the primary outcome, as I say, was days live and out of hospital, the point estimate favored usual care, remembering where usual care is still being able to stand patients by day five, and, you know, sit them by day four.

So it’s not, you know, it’s still a high level of mobilization. But the point estimate did favor for days 11 out of hospital, it favored usual care. And there were less adverse events with that. So, you know, we’re going back to the drawing board a little bit with our group, just in terms of thinking, there’s two things that need to, I think that are really important from the results of the team trial that we’re drilling down into the data for. The first is the heterogeneity of treatment effect, because we do believe that there are groups of patients who did worse than other groups of patients. So there’s probably some baseline factors that are really important. And I can tell you, we think that we’ve identified one, and I won’t talk about it, now, it’s a post hoc analysis and just be hypothesis generating.

But we think that we have identified one group of patients who did particularly poorly, and that that might have affected the results overall. Also, if we can look at the heterogeneity of treatment effect, looking at baseline factors, including admission diagnoses, and some other sort of covariates, then I think that it’s important that we can look at differences there. And the second thing that we think is important, I mean, we’ll do a descriptive paper about him, you know, so there’s a little bit more detail around the adverse events, but it’ll just be descriptive. But we’re really interested in dose response here because, I mean, I honestly do think that what we did didn’t benefit the patients in terms of really pushing their mobilization when we did so.

What does that mean that we have to do differently around our dose? It’s unclear from the data at the moment whether that means that we still get them out of bed early, but we don’t spend as many minutes of time whether we spend the minutes of time but we don’t push the level of mobilization as quickly whether we use a more usual care. But you know, how do we actually define the dose of mobilization? And there’s several, several factors to dose, as I’ve said, it’s the, the intensity of the exercise. It’s the highest level of mobilization, and it’s the duration.

And we don’t know, you know, for example, the AVERT trial (7), the very early rehabilitation in stroke patients trial that was led by Julie Bernhardt and published in The Lancet five years ago, showed that there was harm with very early mobilization in patient patients with stroke, it doesn’t mean you stop rehabilitating patients with stroke. The question is, how do you rehabilitate them and Julie went on to do a cat analysis where she looked at the dose response. And they found that the harm was associated with the duration or longer duration of in terms of minutes of rehab caused harm in stroke patients as opposed to the highest level of mobilization. In fact, the highest level of mobilization was associated with a good outcome, but they had to keep the treatment sessions short. So you know, we’re wondering if with the teen child, there’s a signal between the dose and how we need to think about that. So two things, I think moving forward, that are going to be really interesting coming out of our data will be secondary analyses, looking at heterogeneity of treatment effects from baseline factors, and dose response.

Dr. Wes Ely 31:32

I love that you’re doing that and trying to pick apart duration versus highest level, I think that’s a really smart thing to do, Carol, and just thank you for your due diligence on picking apart these data to generate the hypotheses to move forward. It tells me that you’re not satisfied with the with the the you’re not at the end, do you say “Hey, this is an intermediate point in our learning, where the train is going to take away…is going to leave the station again, sometime in the future to go answer, ask and answer other questions?” Right?

I have a couple of questions for you. One is that a few days after the trial was done after the paper was published, one of your partners started tweeting out “Rest is best”. And, and I wanted to know if you think that rest is best, if you actually think that, and then do you think that the patient’s got more sedation than you then you would like for them to have gotten? In other words, do you think they were over sedated? From a, as Heidi put it, cumulative sedative perspective.

Dr. Carol Hodgson 32:36

Okay, so I’ll take the rest is best first, because that’s an easy one. So Dr. Paul Young is a fabulous intensivist and a friend and a colleague, and he’s actually one of my mentors, and he’s probably one of the smartest trial OSI No, but I think that even he agrees that he didn’t mean “rest is best”, what he probably meant was “less is best”.

Dr. Wes Ely 32:58

What he told me around the world was “Rest is Best”.

Dr. Carol Hodgson 33:01

I know. And don’t worry, I called him out on an in on Twitter as well, you might have noticed my response to him. As you know, I did not agree with that at all. Of course, we have to start rehabilitation with our patients. At some point, the question is, you know, what’s the best timing? What’s the best dose and there patients that are going to, you know, perhaps have a better response, and some patients that might have harm associated with it?

And that’s, you know, these, as you say, when you do a big trial, you know, you try and answer one question, and all it leaves you with is probably, you know, 50 more questions, which are, you know, burning questions. So, you know, I don’t agree that “rest is best” at all, you can see that our usual care was definitely not rest. I mean, in our usual care group, as I said, they were standing by day five, they were not resting, and a very all of them mobilized in ICU like over 90% of those patients mobilized in ICU. So there was no rest in any of our groups. That’s the first thing I’ll say. And the second part to your question was was sorry, just repeat the second part to your question.

Dr. Wes Ely 34:05

I’ll rephrase again, if you look at your lowest level of RASS and your highest level of RASS tables, and believe me, I don’t normally pick apart data like this, but I was so perplexed by what was going on that I actually went through every single day and made a graph just so that I could learn from this. I won’t show it right now, but on your lowest, the intervention and the control group 70, 70, 70 at minus two or less. Then all the way out through eight days Carol, and this is don’t take this as criticism. I’m just actually want to know what you’re thinking. The intervention cogroup were just even-steven out to eight days there was no difference in RASS levels out eight days for lowest RASS or for high RASS it was they were almost identical.

And whenever I look for when I do clinical trials, I’ve been doing them for 25 years, you know is separation of groups. So take people put them, randomize them, and then separate them. And since I think that sedation is so key to the entire thing of: Can you mobilize a patient? What it told me was there wasn’t separation of groups in terms of sedation, which at the bottom…. at the end of the day, I think that what happened was….. be ready, you know, be ready to come on back at me with criticism on this….. I think what happened was that sedation was the rate-limiting step in your trial, because they patient’s sedative levels were so similar the entire way through that there was no way to allow the mobilization to kind of take off in the intervention group. And so I think that sedation level was holding back the ability to do actual higher dose. And that’s to me going to be the main limiter.

Heidi Engel 35:49

Yeah.

Dr. Carol Hodgson 35:50

Okay. So that’s a great question. For starters, we didn’t collect data on, you know, types of sedatives, on the duration of sedatives, or on the dose of sedative. So I can’t answer questions around that. All I can say is that you know, that we’ve gone back through our data really carefully. And that nearly 80%, 79% of our patients had a RASS in the range of minus two to plus one by day three, and, you know, nearly 70% had it by day two. Does that mean that it was sustained and for long enough? Again, I can’t tell you from my data, because we don’t have it. But I agree with you that there was not great separation in sedation between the two groups. And we weren’t aiming to do that all we were aiming to do is to allow the early mobilization group to be sedated long enough to be mobilized.

And we did achieve separation for mobilization. So we weren’t aiming to do a sedation trial, and I agree with you. Should we have?– is another question. That’s that, and it’s a great question. The bottom line is, that’s not what we did. We did a trial where we, we asked for sedation to be minimized in the intervention group to allow mobilization to occur. Mobilization definitely occurred, it occurred early, it occurred at a high level, we, you know, we achieved it a couple of days earlier in the in the intervention group, we achieved it for a longer duration and to a higher level.

So whether people think that’s enough separation between early mobilization and usual care. And interestingly, our usual care group, which people say is a really high level of mobilization, is identical to the usual care group in the schweickert trial. So you know, the Schweikert trial actually also had patients standing by day four and a three standing by day five. So, you know, when we were doing our response to the review, as with the New England, to and fro, we had to actually change a lot of our discussion, because it was pointed out to us that actually, our usual care was the same as Schweikert.

Dr. Wes Ely 37:49

Interesting.

Kali Dayton 37:51

Heidi, any thoughts about that?

Heidi Engel 37:54

You know, I just, I just wanted to offer an anecdote. So I think more than a teacher and researcher, I’m a daily clinician, right? And so a lot of my observations are what I see at the bedside day in and day out. And we have, we have a specific group at UCSF, which is our lung transplant patients, okay. And so we’ll receive these patients from outside hospitals very, very sick and stage lung disease, often needing you know, multiple things done in order to wake them up. Typically, they come from an outside hospital having been sedated or having some superimposed infection on top of their end stage lung disease.

So they’re fairly sick but they really have one major organ system for the most part that’s taken out so I will give you that that they’re not in multi organ failure for the most part, usually. They come in and our lung transplant team is very specific about the must be awake. So they quickly within one day do all their procedures, they there’s no sedation on these patients their entire stay while they’re waiting for lungs and what we watch is day one they they can’t process their RASS zero. So day one in my hospital waiting for lungs having a workup for lungs and they are hard to mobilize because they’ve been lying in bed they’ve been sedated now the sedation was turned off hours and hours before I’m seeing them and they are technically a RASS zero.

However I can’t do much with them they’ve now spent a week or something in bed and and outside hospital receiving sedation and this is all kinds of baselines young, old, etc. So they want to can’t do much. There’s tons of anxiety for the patients like what’s going on the families looking at me saying what’s going on, you know, they shouldn’t be lying in bed. That’s what we were told to the outside hospitals gonna be dangerous to move them. They’re gonna desat, all these things. That takes a couple of days of NO sedation for two days for me to help work it through with everyone. But by day three, those patients know the routine, they’re gonna get up out of bed, they’re gonna walk down the hall, they’re gonna sit in the chair for a while, they’re gonna get a little bit tired, they’re gonna get back in bed, someone else is going to come along later in the day and repeat the process.

And then once they’re in the routine, and once we’ve had days to dial back the sedation, to help them make sense, to empower them to participate in their care, they can do much higher levels of mobility much safer. But my other patients who are in the medicine and ICU service very often will come in, and they’re being sedated for their critical illness. But then we’re afraid to take the sedation back or with everything that happens going along the way, which sometimes it’s about them, but frankly, sometimes it’s about staffing or individual person’s belief about sedation. And so the sedation for that population, very often I find is going on and off and on and off.

And if you average their RASS, it could be minus one, if you looked at their median RASS, for an overall period of time, you could say, “well, but they were RASS minus one.”– But they weren’t because they were all over the place, depending on who is at the bedside. And what are the particulars of that day. And so I’m in that, like, what I just described, the first two days of my lung transplant patients, I’m constantly in that cycle. I can get them to stand, I can maybe get them to get to a chair, they’re gonna get exhausted, they’re sort of understanding, they’re sort of not, they want to try because at this moment, they’re a RASS zero.

But I’m going to come back tomorrow, and they were on sedation last night. And we’re kind of starting over and over again. And I don’t progress very far in their mobility. And I know from Polly Bailey’s one published study(8), and I think it was in 2008, and critical care medicine or 2007. So it’s not a new study, that protocol that they employed, of having the person just be awake, like, let’s just turn the sedation off and leave it off. And it was really that system of having the patient on zero sedation for days and days and days, and a protocol and a normalization of by the staff of like, Yeah, our patients are like floor patients, they should be awake, they should be getting up out of bed in the morning and heading down the hall. And these are patients, right, the median, the median APACHE 2 score for them was 26. And they had P F ratios of 100. Right? In that study! So these are really sick ARDS patients who were capable of getting up and walking down the hall simply because people turn the sedation off and never turn it back on. At all. Right?

Dr. Carol Hodgson 43:02

I don’t, I don’t disagree at all, Heidi, but that was in medical patients in a single center. And I do think that when you look at a big multicenter study with a mixed cohort, surgical trauma, medical, it’s going to give you a different signal, there is going to be noise in the sedation signal. And now I’m not saying we got it right, I’m not saying it’s perfect. We didn’t actually even try and address the nation other than to say that we needed patients to be designated to allow mobilization in the intervention group. So I am completely not disagreeing with you. I agree with you. That’s a great study. She showed us how, you know, I completely agree Polly Bailey showed us how it can be done and should be done. Taking into account that that’s in a strictly medical unit where, you know, there weren’t perhaps some other considerations that we had around some of our patients.

Kali Dayton 43:54

And I’m just waiting with baited breath for their COVID retrospective study, comparing their treatments and outcomes to the other COVID ICUs within that same community hospital system, I think there’s a lot to be learned from that. That, to me is a big gap in the research is comparing even the control group in your study….. what if we compare that to the Polly Bailey method? Would we then see a difference? I mean, anecdotally, I have teams reporting a 75% reduction in length of stay. I mean, they’re small, it’s anecdotal thus far, I wouldn’t publish that quite yet. But I am seeing a reduction in length of stay by changing sedation practices, which then enables mobility even more.

But Dr. Ely, I have a question for you. I’m still always learning about the history of the ABCDEF bundle. I have always wondered about some of the semantics behind this protocol. So we say “vacation”, we say “trial”, “sedation vacation”, “sedation trial”. I wonder and I see sometimes that even just those words, is part of the problem. I don’t mean that critically, but when I talk about when I teach teams about certain practices, they feel like they’re practicing the ABCDEF bundle, but they’re commonly doing what Heidi is describing. Turning it down to see patients thrash, consider it a fail, and then resuming it and calling that a “failed trial” and they did a “vacation” instead of this perspective or this expectation to turn off sedation or to get to a RASS of zero. Any thoughts about that?

Dr. Wes Ely 45:29

Yeah, you know, Gita Mehta did an investigation (9) in Toronto and Canada of the, the ABCs, the awakening trials and the breathing trials. And in their culture, the nurse and I was at their hospital, I would talk to those nurses, I spoke to them myself at the bedside to understand what had happened there. And they said, “Oh, well, we did the trial. We turned the drug off. But then as soon as Geeta, as soon as Dr. Mehta walked away from the bedside, we turned it back on.” And I said, “Why do you do that?” And they said, “Because we believe that the right thing to do for patients is to keep them with some sedation on board.”

And what they showed was that there was a dramatic increase overall, in the amount of sedation delivered to the group who got the daily awakening trials. You heard me right, those who got the daily awakening trial has gotten more benzos than those who didn’t, because the nurses felt like they were having to play catch up to get that drug back into the person because in their mind, the right way to care for the patient was to protect them with a drug. This is this is a mindset of chemical restraints being the best way to care for a human being.

` And and and we know, for example, from over 35, randomized controlled trials of benzodiazepines that they lose every time, there’s never been a comparator against the benzo or the benzo one. Because anything that does this to the brain worsens patients outcomes. And that’s why at the end of the day, you we can’t, whether it’s the team trial, or any of these other eligibility trials, we cannot achieve ocular management of a human being on an individual basis or on a population basis, unless we change the spirit of how we go about looking at people.

And I say that we have to look at our patients and say “Not what’s the matter with them. But what matters to them?” we have to switch the preposition from with to to and say on each person’s bed, what matters to you, and if what matters to them is to be awake so they can talk to their loved ones awake so they can hear what’s supposed to be going on in their lives. And they can hear the progress here the directions from the physical physio, then then we are not putting them first, when we keep them deeply sedated.

This is not an indictment of team. This is an indictment of all of our management. Because we In other words, when when you said Carol, we did what the study was set out to do you absolutely did no question. And what I’m saying is that until you achieve separation of groups, at the level of sedation, we will not see an optimized or low mobility plan, period. That’s my one thing I would leave you with all of us with is that all of us will fail the patients unless we actually achieve some difference in the way we’re sedating them.

Kali Dayton 48:20

When I share with teams that the real vision and mission of the ABCDEF bundle is to create patients that are more awake, autonomous, I quote Brenda Pun on this, communicative, mobile that that is the purpose. It’s not just to do an awakening trial and then turn sedation back on, that is not the A to F bundle, the A to F bundle is to have patients awaken mobile, unless there’s a specific indication. And then those tools within the ATF bundle help us guide how to minimize duration and dose dose of sedation. Right? But when I share that, people are shocked. That they did not know. That it’s not the culture, that’s not the perspective given with the A to F bundle. So I feel like we’re really missing the true vision of having an “Awake and Walking ICU” that patients that are sedated, even to a RASS negative two should be the exception, and not the standard. And until we do that we really can’t optimize mobility and maximize outcomes.

Dr. Carol Hodgson 49:14

I guess, just on a final note, I’ll say and I agree with everything you’ve said, I I am a huge advocate for sedation minimization. In a prolonged state like Heidi, I’m also a clinician I work at the bedside regularly. You know, I don’t like if our patients are left sedated and just woken up for short periods of time. That’s not the way that we like to manage patients, either. Although I am afraid that you know, it is more common than I would like. But I guess what I would say about the coming back to the team trial, just to finalize is that even if we had achieved perfect separation in sedation, would that have achieved more mobilization than what we have quite possibly would that have had a benefit? I don’t think so. Because what we’ve seen is with the small separation that we have between the groups in mobilization, we were the point estimate in the primary outcome still favors the control group, which is still a good level of mobilization. But it’s not very, very early mobilization.

And it’s not the sort of intense mobilization that we achieved. And we still have more adverse events that were mobilization related. So if we’d had more mobilization, I’m worried we would have seen more adverse events, and and that it may not have benefited, you know, so, I mean, I guess I’m hypothesizing but I guess what I am saying is that, perhaps in a future trial, we should plan better to implement the ABCDEF bundled together to make sure that sedation is a priority with mobilization. I take that point on board.

And I completely agree. But what your I guess, what I heard, what I’m wondering if you’re implying is that if we had done that, and we had more mobilization, that that would, equals success. And in this case, I’m actually not sure that it would, and I don’t think that we can say from the results of the team trial, that that’s what would happen. So lots of food for thought. And please stay tuned for the post-hoc analyses that we have planned, because I think they’re going to be super informative, and really helpful to drive this program of research forward, and also to help inform clinicians about some groups of patients that may benefit and some groups of patients that may actually, you know, be harmed by early mobilization.

Dr. Wes Ely 51:24

I want to be very generous in my interpretation of what you just said, because I think that that, from the data at hand, you actually are making a very well thought out statement. And I think it’s brilliant, and you’re obviously a great investigator. I just one thing that has not been said during our entire hour together yet, is this, that let’s not underestimate the systemic effects of these drugs, because it is not just about the ability to let the patient wake up and have their arms and legs work, these drugs are toxic to multiple organs in the body.

So Carol, if the drugs overall had been given less, and there was a true separation of groups, there will be actually a body wide, I’m hypothesizing here, I would, I would propose that there would be a body wide allowance of greater healing to go on from the head all the way to toe, and it wouldn’t be measurable just by the dose of the of the of the mobility. So what you have at hand is two groups of people both getting very, very similar levels of the sedative drugs, not separated out by your own data by their own, you know, highest and lowest RASS. And so what I’m saying is that when that happened, upstream of your attempt to immobilize them, their entire body was involved in this situation, and it leveled the playing field is that’s what I’m hypothesizing the level the playing field was leveled by the drugs upstream from the beautiful attempts of your trial to separate.

Heidi Engel 52:59

Yeah, and I think I think I think the mobility is, is getting a rap for the adverse events when we don’t know that right? Because it’s in my mind, just based on what I see at bedside each day. It’s mobility, plus the sedating drugs that don’t really contain nearly you know, the impact on the brain and everything else. The mobility plus the sedation is when I see more a fibs, and when I see more irregular blood pressure responses, so

Dr. Carol Hodgson 53:34

I thought I did a randomized trial. But in a randomized trial, if we’ve got no difference between the groups and sedation, and we do have differences in the groups between mobilization and the adverse events were associated by the investigators with mobilization, then I don’t think that that’s accurate. Heidi, I actually think you have to say that it was either as a result of the mobilization or the only other question here is whether there was reporting bias because people had eyes on the intervention group more closely than on the control group. So it is possible that there is some reporting bias. Otherwise, I think in a randomized controlled trial, where the only difference was level of mobilization either Yeah, it’s hard to refute that. That is a great point.

Heidi Engel 54:16

Yes. But I think all I’m saying is, is that probably the sedation plus mobilization gives you more adverse events, where as perhaps, and again, it’s a hypothesis perhaps if the intervention group got the 20 minutes of mobilization, and no sedation, there would have been less adverse events. That’s what we don’t know. Right. And so to just give a blanket statement that will look this extra mobility is harmful. Yes, in a group that is receiving these levels of sedation, but our question that still remains is, would it be harmful if the patients were awake and this addition had been off for all these days.

Dr. Carol Hodgson 55:03

I think that’s a great question for our next trial.

Kali Dayton 55:08

All these different trials, I mean, from this discussion, I hope they come to fruition.

Dr. Wes Ely 55:13

From a trial perspective, the hard thing is, let’s, let’s look at three different types of trials. And I’ll be very brief, one single center, where you can totally control everything about what’s going on One an intermediate size, let’s say five to 10. Centers, okay? We’re like in the mind USA study (10) where we can really, really hone down and when I say babysit a study, but the one disadvantage Carol, that you’re at when you have such a huge network, is the inability to keep eyes and ears on all these study sites. And when I say babysitting a study, it’s basically impossible when you have 80 centers or whatever, when you’ve got to babysit. And so what happens is you are subjected to the culture of all those ICUs. And it’s not possible to change those cultures within the context of a protocol. So what do you think about that? Is it that you agree with that? It was out of frustration of yours?

Dr. Carol Hodgson 56:05

No, yes, yes. And no, it’s I guess, we believe in, you know, large pragmatic trials, like ripple, you know, we try and implement it across as many centers as possible to try and get an answer about sort of implementation widely and broadly and globally. That’s what our group sort of well known for. And that’s what we do. And, of course, the single center trials in the smaller trials have to be used early to inform a larger trial, which is what we did. So we did, you know, we did our observational study, we did our single center study, we did our six center randomized control trial just across Australia, New Zealand to inform our larger trial.

So I guess that was all of our preparatory preparatory work before we performed our big phase three trial, but the phase treat and endow pilot trials, you know, had an indication that there might be benefit, which is why, you know, we were funded to do a bigger trial. So I guess the question is, then when you do implement it worldwide, and you do say, Okay, well, let’s throw out early mobilization and push it as early as possible. You’re not babysitting sites, you’re giving them a protocol, you’re asking them to follow a protocol. You’re asking them to randomize patients. And you know, you’re right, you don’t have the control. But what you find out is whether when you implement that at a global scale, whether that will cause benefit or harm. And you know, this answers one little bit of our question, but as I said to you, we’ve got, and I’m pro mobilization, our usual care group got a really good level of mobilization. I’m certainly not throwing out the baby with the bathwater here, and I do not agree with rest is best at all, there was no rest in this trial. But you know, we have a lot more questions to answer. And, you know, we’re really excited to move forward with this program.

Heidi Engel 57:42

I just want to ask one last question to the group. And that is, so probably the study that I cited has been out there since 2007. And Kali’s podcast is very much based on what we’ve read in the in that study, but I have never seen it replicated, right. I’ve never seen that protocol replicated, or, as Carol suggested, put into a larger style. You know, here is your one center, you know, descriptive study of what is possible, but no one’s ever really tested it right. And I think that’s a very intriguing question for the future. Wes and Carol and Kali because, you know, that’s a very different protocol than we’ve seen. And I read everything, right, we read all the early mobility trials, and I’ve never seen a protocol that one stands way out different than the rest. Just as all the things you’re talking about on your podcast, Kali really stand out very different from what is standard practice. So even in a pro mobility proactive bundle ICU, we still none of us are doing what you are trying to ask the world to do. And so when are we going to have this study that that uses that as the protocol that’s handed out to so many centers?

Dr. Wes Ely 59:04

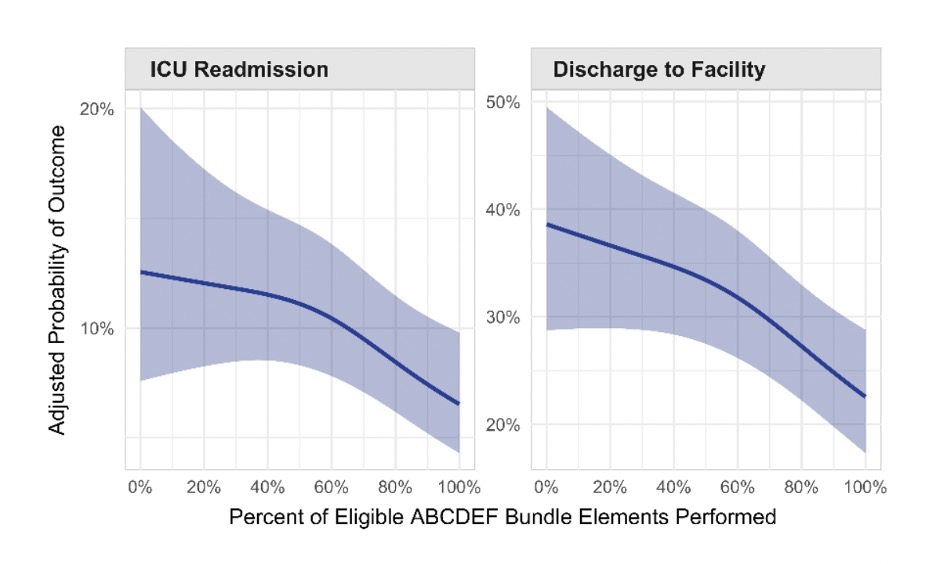

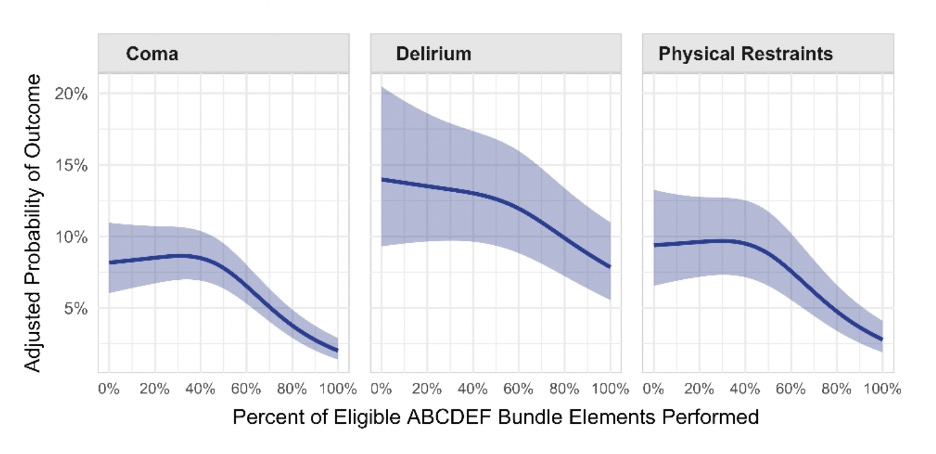

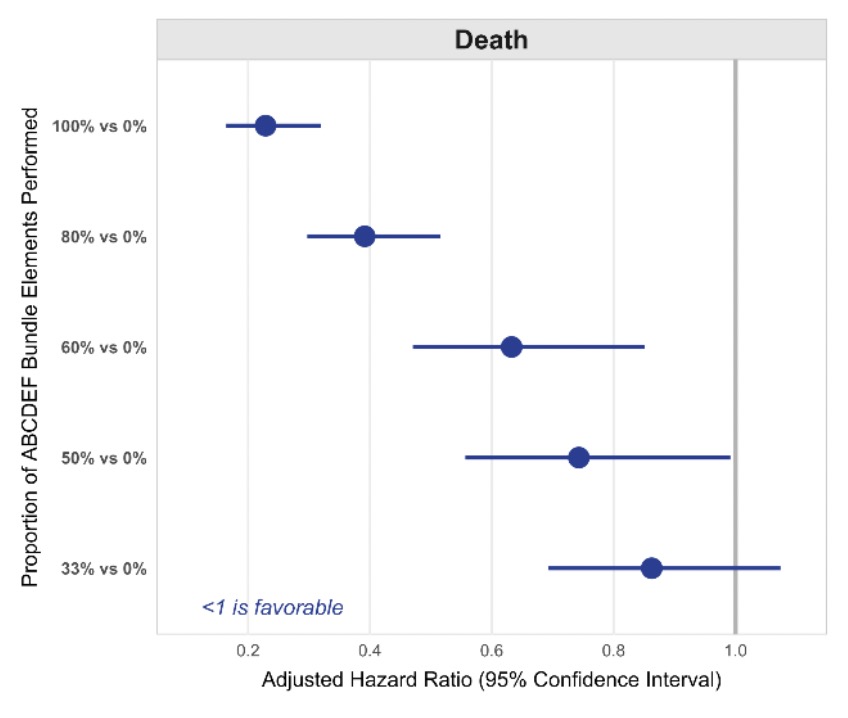

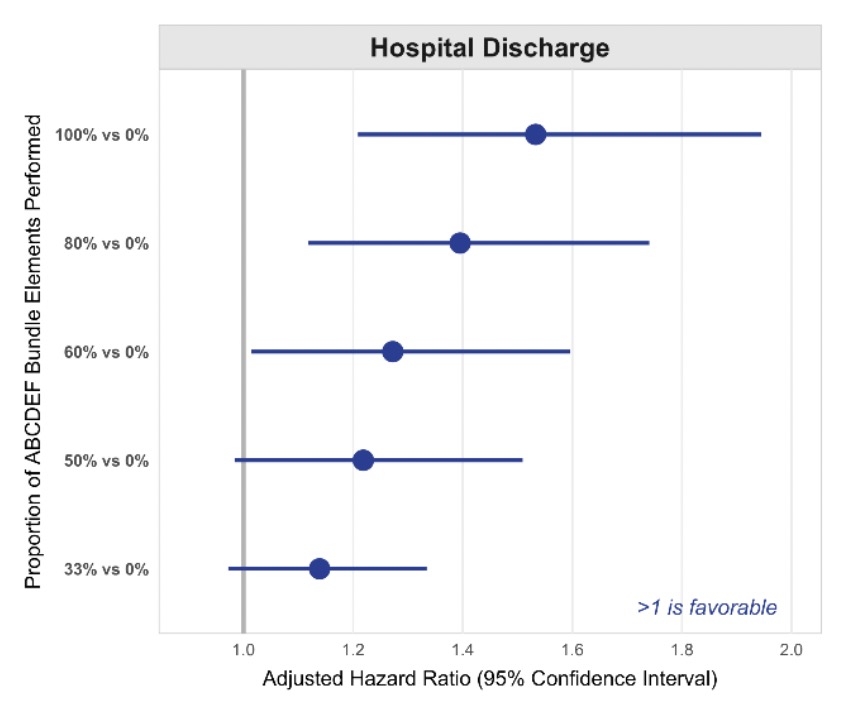

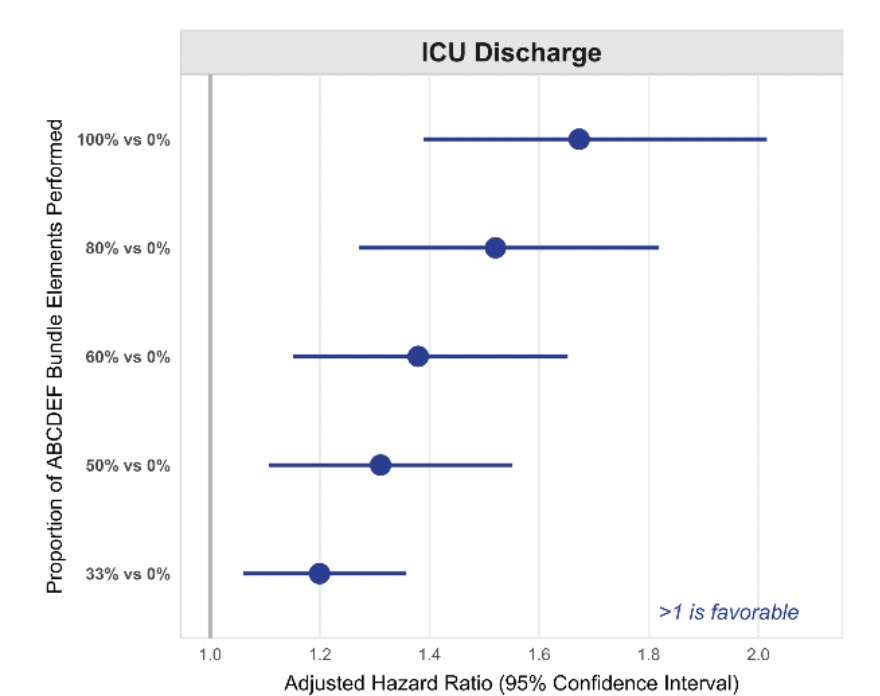

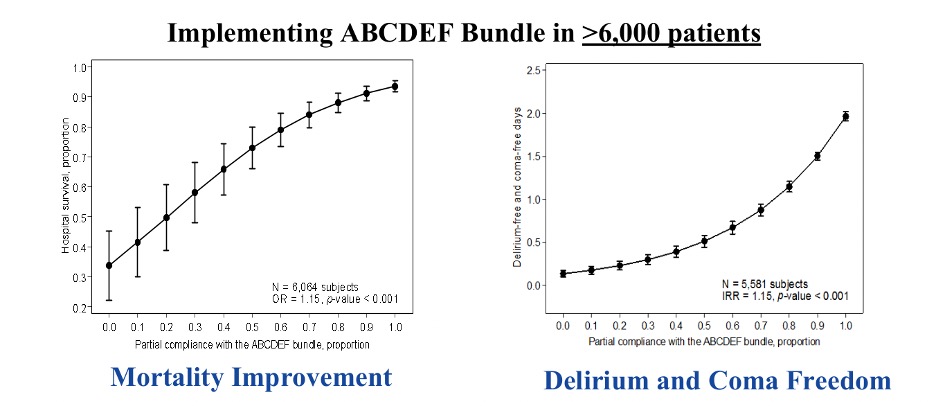

Well, I’ll give you this risk response. Although her let’s let’s say that hers was the absolute “No Sedation”, which it was, and the results were let’s call that 100% compliance with the bundle of A to F bundle in our 15,000 people that were in the ICU liberation cohort study (11) a year long quality two year long quality improvement. Remember that we saw a dose response, but from zero to 20% to 40% to 60% to 80%. The further you went towards Polly of Polly’s 100, the better you got in terms of decreased length of stay in a hospital ICU, less death, less ICU bouncebacks, less delirium, coma, everything dose response, went in the direction towards Polly’s perfection, as you went away from Polly and A to F bundle 15,000 people, you got more and more badness.

So I would say although wasn’t a randomized controlled trial in 15,000 people. We saw Polly’s situation replicated in a dose response. And we also saw that replicated in 6000 people in Marion Barnes-Daly’s (12) study two years earlier, which was with Sutter Health at nine ICUs in the, in the Southern health California system, dose response once again.

So I think that Polly has been vindicated, if you will, she’s been validated and vindicated that yes, when you put this out there in the real world, and most of the A to F bundle is about what Kali said earlier, which is a systematic, waking people up throughout the day, it’s not a one hour shut off, and then turn everything back on. It’s a culture shift of “Awake ICUs”. When that spirit is adopted, we see these results.

Kali Dayton 1:00:50

Would you do you support the continued culture of automatically sedating every patient after intubation?

Dr. Wes Ely 1:00:57

Are you asking me? Uh huh, no, I sedate my patients for the intubation. And then during that day, they get sedation. And then the next morning, when I say when the sun comes up, their sedation is coming off. And even in COVID, when we were using ridiculous high respiratory Fi02s and peeps, the nurses would say, “You’re kidding.” I say “No, let’s turn it off. Because she’s got to see her husband. She’s got to see her husband, this woman who delivered for babies, she just given her better birth, their fourth baby, I said, she’s gonna forget why to live, if she doesn’t see her, her husband, James.” And so when she saw her husband, he’s like, “Honey, you gotta get home, I’ve got to have you there.” And she remembers, “Oh, this is my WHY to live.”

Kali Dayton 1:01:45

And I would love to see that somehow studied. So the impact of the will to live on survival, and how sedation practices and delirium impacts the will to live. There’s so much that we can dissect and glean from this. But thank you so much, Dr. Hodgson, for your incredible dedication to these important questions keep us posted on what comes up later, and what we continue to learn.

Dr. Carol Hodgson 1:02:08

Thank you for having me Kali, I really enjoyed it.

Heidi Engel 1:02:11

It’s brilliant. You always do brilliant work. Thank you for for joining us,

Kali Dayton 1:02:16

Absolutely. And I think we all are on the same page. And I think everyone’s individual efforts here are going to bring great changes in critical care medicine of the future. Thank you so much.

Dr. Wes Ely 1:02:26

I want to congratulate all of you on being champions for the patients because all three of you are just leaders in my mind, and you’re helping me do a better job every time I walk to the bedside. And Carol, your greatest work has just come out in the New England Journal. But I don’t think it’s your final best work. I think there’s more to come.

Dr. Carol Hodgson 1:02:44

Thank you. And I really, really appreciate the dialogue that we’ve had over the past month or two, just you know, trying to tease out the findings. And Heidi, it’s been such a pleasure to speak with you. Thank you. Thanks, Carol. Thank you

Kali Dayton

I loved our discussion with Carol Hodgson. I deeply respect her devotion to early mobility. Her passion for studying and promoting early mobility resonates with me. I know that she does not wish for her work to be misinterpreted, and yet I have been concerned by the response to this study in the ICU community. I have had leaders of ICU teams say to me, “Well, now there’s the TEAMS study that showed that early mobility doesn’t help patient outcomes.” Hopefully, after listening to this discussion, you are prepared to clarify this study with your colleagues.

I also want to emphasize the importance of sedation management in these studies and at the bedside when it comes to early mobility. I visited a team for a gap analysis a few weeks ago. In their defense, they did not do webinars with me prior, and so they had very little preparation for my approach. They understood that we were there to help them practice early mobility. When I broached the topic of improving their sedation practices, they seemed bewildered. They didn’t understand why we were talking about sedation when we were there for early mobility. To me, this TEAMs study reveals that gap in our approach. We cannot truly master early mobility and give patients the full benefit of early mobility if we first cause acute brain failure and more muscular atrophy for days prior to attempting mobilization.

Please check out the blog for this episode. Dive into the citations, look at the graphs provided. Check out the graph from another recent early mobility study. This is a good example of how sedation should be tracked in such a study. We have to look at the whole picture.

I invited Marc Moss to share some insights. He is the Professor of Medicine and Head of the Division of Pulmonary Sciences and Critical Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. He has vast experience with research and has been a principle investigator for over 19 years.

Kali Dayton

Hi Marc, thanks so much for talking about this study with us just conclusion of what you and I have, and how to echo what we’ve been chatting about. What are some of your insights or takeaways from this team study?

Marc Moss

Well, Kali, first, thanks for inviting me to participate. I think this is a very important issue that requires further discussion. I think the take home points for me about the TEAM trial, as I said, in the editorials that the trial was designed to test different doses of early mobilization.

And it should not lead to the conclusion that early mobilization is ineffective in general. And I think that was a concern of the editors of the New England Journal of Medicine, and why they wanted an editorial to try to put the study in the proper perspective for the clinicians who are caring for these patients.

Kali Dayton

And what are some questions left unanswered in your mind after reading this study?

Marc Moss

Sure. I think the team study was a well done study. But I think it also shows that we’re in our infancy still, a decade later after, we start to think about the role of early mobilization for our Intensive Care Unit patients. And I think we need to potentially take a step back and think about how to identify patients who will receive the most benefit from early mobilization, how we can risk stratify patients in a more effective way.

Because I think it’s not correct to have physical therapists performing early mobilization on everyone in the intensive care unit, I think we have to tailor the therapy to the individuals that require or will receive the most benefit from the intervention. And in addition, I think we have to design studies that have the appropriate comparison groups, I think that was a an issue with this study, there wasn’t great separation between the two groups.

So it makes it harder to identify a difference when there’s not a big difference between what the two arms of the study were getting. I think we need to identify outcome variables that are attainable, and inform clinical practice. And then really, at the basics, we need to determine what are the appropriate types of therapy? When should we started? How do we start it at an earlier time? What’s the right intensity? How do we coordinate it with the nurses and the respiratory therapists, and then the duration of therapy. We’re critical care doctors, but their weakness doesn’t end when they leave the ICU. It’s really just the tip of the iceberg. And we need to learn how to coordinate potentially longer durations of therapy that extend to the regular wards in the hospital and maybe even the outpatient setting.

Kali Dayton

And any thoughts about the role of sedation that may have played into the overall outcomes of the study?

Marc Moss

Yeah, I as as they showed, in one of their supplemental figures, one of the biggest barriers or the biggest barrier, in their early days, when patients were enrolled into this study, the biggest barrier was sedation and delirium. So if we’re going to stick with the theory that starting these interventions earlier, like most interventions are going to be more beneficial than we have to figure out what to do with sedation strategies with delirium in these patients so that we can potentially deliver the optimal duration intensity of therapy at an earlier point in time.

Kali Dayton

Absolutely. And I want to include also for the listeners, the median time of enrollment for these participants was what was 60 hours? Right. So I would assume that those that are on sedation starting on day one of the study, were also spending about two and a half days sedated prior, would that probably be a safe assumption?

Marc Moss

Yeah, I would, I would think so. Again, that’s where doing studies and what we do in clinical practice, are not always aligned. To do a study like this, that you have to have a research staff that screens patients, identifies them, finds families, and I think in critical care research, we’re getting better at identifying people early.

I can tell you in the neuromuscular blockade study that we did that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine, our time from them meeting the inclusion criteria for the study to being randomized was, I think it was nine hours, if I remember correctly. So shorter than 60. So there are ways to enroll people earlier. But sometimes it just takes a while to identify families and get studies up and going for any individual patient that then inhibits the ability to understand how to trans form that into real clinical practice.

Kali Dayton

Absolutely. And speaking of real clinical practice, what would you invite the ICU community to do in their clinical practice as a response to this study?

Marc Moss

That’s a really hard question. Because I think part of this study examined a slightly more intensive strategy versus standard of care, and the standard of care in in the hospitals that were used in the studies that 81% of the ICU days, in the usual care group, patients were assessed by a physiotherapist. And, you know, I think that’s a really hard question. I’m not sure this study is definitive enough to inform people to change what they’re doing currently, though, I can’t say what they’re doing currently is correct, either. So I’m not sure this study can tell people to change their practice in a significant way.

Kali Dayton

That’s a great answer. Thank you so much. Anything else you would share?

Marc Moss

No, I think I think that’s, that’s great. There’s just it’s the typical thing people say, but there’s just a lot more work to be done in this area, to really understand how to get the right. therapy to the right patients.

Kali Dayton

Absolutely. And which is overwhelming, frustrating, but also exciting. And so thanks for helping us dissect this and we look forward to the future.

Marc Moss

Sure. Thanks, Kali.

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

References

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19446324/

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00134-016-4321-8

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27707496/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36278257/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28231030/

- https://daytonicuconsulting.com/walking-home-from-the-icu-podcast/walking-home-from-the-icu-episode-21-what-weve-always-done-isnt-always-right/

- https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/strokeaha.107.492363

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17133183/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23180503/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30346242/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30339549/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27861180/

Other Studies Supporting Efficacy, Benefit, and Safety of Early Mobility:

Library of early mobility studies.

Each level of mobility decreases the risk of hospital and ventilator-associated pneumonia by 40%.

Early mobility reduces the incidence of delirium.

Early mobility lowered depression, anxiety, and PTSD after the ICU by 26%.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE PODCAST