SUBSCRIBE TO THE PODCAST

What happened when I was reported to the board of nursing for advocating for early mobility in the ICU? What are the roots of these concerns and this report? How does social media impact culture and practices in the ICU? Jess Hren, BSN, RN, Jenna Hightower, DPT, CCS, Phillip Gonzalez, MOT, OTR/L, BCPR discuss why I was reported to the board of nursing.

Episode Transcription

Kali [00:00:04]

This episode’s title makes this episode sound really salacious, but it’s not supposed to be a gospel session. Yes, I was reported to the Board of Nursing but there’s a bigger picture here. Before we can dive into the main discussion, I want to introduce my friends that are here on the podcast episode with me. Jenna, would you start?

Jenna [00:00:22]

Sure. My name is Jenna Hightower. I am a critical care physical therapist. I did a residency and critical care and have worked ever since out of school primarily in critical care, mostly CVICU and MCICU areas. But a little bit in neuro ICU areas in some major hospitals here in the southeast.

Kali [00:00:45]

And you’ve been on to other episodes, and so it’s fun to have you back. Go ahead.

Philip Gonzales [00:00:51]

Hi, everybody. My name is Phillip Gonzales. I’m an occupational therapist. I practice in the ICU for about the last 10 years now. A lot of my background comes in multi-specialty ICU units that include neuro, trauma, CVICU, as well as single origin specialty ICU units. I’m board certified in physical rehab and as Jenna, I also bid on two former episodes with Kali Dayton

Kali [00:01:20]

And Jess. Welcome. This is your first time.

Jess Hren [00:01:25]

Hi. I’m Jess Hren. I’m an ICU nurse. I’m primarily a travel nurse now. But my bread and butter is community hospitals and medical ICUs.

Kali [00:01:34]

And how did you come to be on this podcast? This is my favorite.

Jess Hren [00:01:39]

I came to be on this podcast because I made it my life’s mission to entirely disprove everything Kali was saying. That’s a new grad. I heard Kali talking about walking patients on ventilators. And I saw I specifically a video of someone walking on CRRT with the dreaded green being Prisma state machine. And I was like there’s absolutely no way. This is a real thing and there’s absolutely no way. This is good for patients and so I started delving into the research and I was like, “Oh crap, she’s right”. And I really hadn’t had any support from my educational experiences up until that point, to give me the information I needed about this. So that’s when I started continuing to listen to the podcasts and delving in further.

Kali [00:02:28]

And you have throughout the year sent me amazing stories and experiences and testimonials and what you’ve applied these principles to your own patients and had incredible outcomes. And so, I’m really excited to hear your perspective and everyone’s perspective on the situation that happened on social media. Because obviously, you would become exposed to this through social media, you were doubtful, and yet you did your homework. But the situation in which I was reported, the board of nursing was rooted in that similar exposure online, but the audience was not so receptive. I mean, not that you were initially receptive that you least went to the right sources. So, let’s talk about the context in which this happened. Let’s talk about memes. I think most of us can agree that memes are so important to deal with a lot of the trauma, a lot of the challenges, a lot of the difficulties that we face in life, but especially in the workplace. It helps unite us were joking about the same things about where the meds from the pharmacy. It helps us feel understood, it helps us talk about things that might be hard to talk about but in a funny way. We can use memes and things like that to have positive things to help bring in more humanity into our care. But also, memes can become very detrimental to a process of care. We can joke about things that are actually very sacred, or are very lethal, and we can normalize those things. So, what are your thoughts about where social media culture is act within the ICU community just in general?

Jenna [00:04:17]

I feel like you said, the ICU is a hard place to work. It is physically, emotionally, mentally challenging for every minute that you were there every day. And I think humor is a way that we try to cope with that and a way that brings us together. Because you’re in the trenches every day, looking at all of this stuff and being exposed to these really sad stories and taking care of these people when they’re at the sickest points in their lives. And my mind automatically just goes back to the pandemic and just kind of the trauma that I have from that. And you know, the girls that I would work with in the COVID ICU and we literally had a coat closet as a office because we weren’t allowed to go down to our office and just the jokes that we would joke during that time. But you know, there’s a really fine line on what’s appropriate and what’s not, and what can be harmful, and what’s not. And like you said, making these things that are harmful and norm is a problem. That’s something that I think that we need to talk about, and talk about why we’re having this episode, and why like some of these normalizations, and these myths need to be debunked. So that we are not making them a normal thing and that’s why I’m here.

Philip Gonzales [00:05:46]

I think you, Kali, and Jenna, said it really well. Really, ultimately, the social media pages had been pages are a form of trauma bonding. It’s a coping mechanism. We see a lot of death and near death experience in the ICU. We see things in our daily practice that the normal individual does not have to deal with. How do normal individuals cope with that? All of us are very different. Most people, especially healthcare providers. We are thick-skinned. We are able to cope in a variety of strategies, whether it be bonding with our coworkers, whether it be expressing our frustrations, our anxieties, and are also our positive stuff with our family. But then also we can use sometimes those memes in a positive light too, like you had mentioned. And I want to highlight some of that stuff too, because I think social media has the power to go both ways. It can be both helpful to patient care or as I mentioned it can be harmful to patient care and to ourselves as healthcare practitioners. And when is too much too much?

Kali [00:07:00]

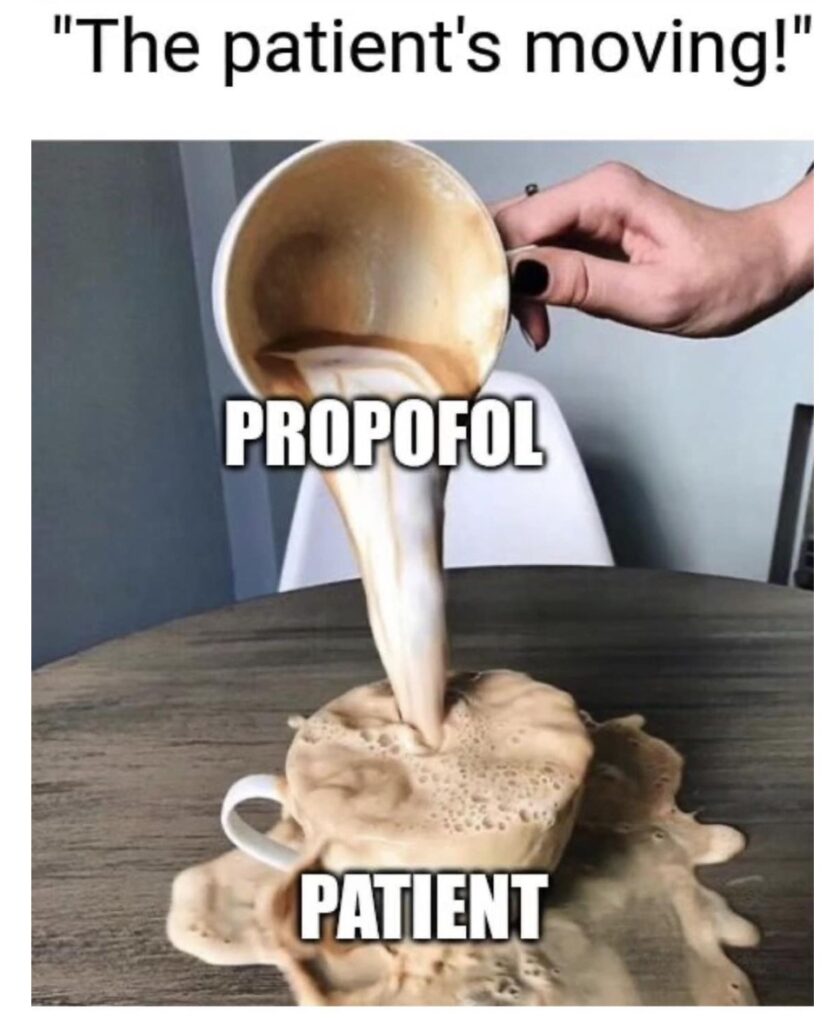

Let’s give an example of too much is too much. There’s an anonymous, or there was an anonymous nursing content page and had lots of memes. And admittedly, they were usually really witty. Many were very funny and they had gained quite a following of like, what 46,000 followers, and there were sprinkled throughout that page a lot of jokes and memes that really concerned us. For example, one meme had a picture of a cup of coffee, and there was a cup being held by hand above that with creamer. And it was pouring it creamer into the coffee and overflowing and it was labeled as the creamer was propofol. And the coffee was when a patient moves a finger. Mean, and insinuating that if a patient was a finger, we can crank up the propofol and douse them. And in the comments, it validated what that was saying. Saying things like, make it’s “no, knock them out.” Things like, “Always chart a RASS negative 2 wink, wink.” Just all these comments reinforced, the things that we talked about here on the podcast that are raw scores are not accurate. That we’re overstating patients, and it was really alarming to the ICU revolutionist community to see that. Not only is that happening, but maybe there’s some awareness that that’s happening and there’s even joking about it happening. So, Jess, I especially wanted to hear your perspective as an RN. How does that? What does that mean really say to you, and what are your concerns about it?

Jess Hren [00:08:39]

I want to start by saying first and foremost, we were never taught at least my era of nursing, which is from five years ago. We were never formally taught how to do a RASS assessment. And I think people think that’s an ICU specific skill, but it definitely like, it follows you out of the ICU when you’re giving patients opioids on a step down unit or a med surg unit. You have to be able to chart that RASS. You have to be able to justify saying, Hey, I did not overstate this patient. I did not send them into a respiratory arrest kind of situation. But we weren’t taught that. And then talking about, you use the term validating and I really liked that because I think as much as memes our way of trauma bonding, ICU nurses are not known for being these remarkably empathetic and emotionally communicative beings. So, the way that we test the temperature, test the waters, so to speak about our practice, about how we feel about our practice, tends to be with these memes. So the make-it-snow memes or the propofol memes.

A lot of times I perceive those as being a way of saying, “Hey, it’s not just me, right? There are other people who do this, right? I’m not in the wrong and it is a standard of care. “ Quotation marks, air quotes, standard of care. It is what we do by nature because we weren’t taught the risks of prolonged sedation. We weren’t taught normally how to do a RAS assessment. Shout out to all my preceptors, who were like, what are you doing? That is not a RAS of negative three, figure it out, girlfriend. But not everybody has those resources. So, coming from a place where I was a lot more comfortable with a RAS of negative three, negative four. And also coming from a place of not knowing what a RASS of negative three, negative four actually meant. I would say that we have normalized and validated our lack of knowledge, and made it more acceptable, instead of seeking out further knowledge, and that’s not to speak down on anyone in the nursing community. But if you don’t have time for lunch, how are you going to have time to further your knowledge on these topics?

Kali [00:11:05]

And when the perception is that’s sedation asleep, that’s more comfortable for patients, what’s the harm? We see these medications as benign, not only benign, but as humane. We’re doing them a favor.

Jess Hren [00:11:19]

That’s the other thing is, I saw a comment that was like, we use propofol to make dogs comfortable during sleep, and we won’t extend that courtesy to humans. And as well, we’re treading in some murky territory comparing human beings to dogs. And I’m not going to touch that with a 10 foot pole. But I think that is like, what we perceive it as like, this is an act of mercy. It’s easier for me to see you like this. So clearly, it must be easier for you to exist like this.

Kali [00:11:54]

Yes. And if it’s not harmful, if it’s the kind thing to do with the harm in given little extra, or, I can joke about its convenience for me, because no, it’s no harm to the patient. When I asked on social media, if these jokes are being made at the bedside, like 94% said, Yes. And when I asked, do you believe that these memes, this online content, influences practices at the bedside, 97% said, Yes. So, I think this, especially for our younger, vulnerable nurses that are not taught about delirium about the risks of sedation, they never got to see patients really be awake and mobile. They came in during COVID, in which deep sedation and immobility were the norm for everybody. If they’re never taught that, and then we have online content, making a joke out of it. Again, validating that encouraging that. And it was not just this one meme, there were a lot of different videos about. Again, “if patients are moving, give him propofol give him a bolus.. It was just eventually became constant. I think, especially as they discovered my page, they were inspired even further to create more content surrounding this. One follower on my page said, “This has joked about all the time at the bedside, so much so that it took a student nurse reporting the other nurses to make it kind of stop.” Which I thought was telling really alarming that sometimes it especially when we’re in this culture, we can normalize these things to a point of we don’t even hear our own selves. We don’t even know what we’re joking about. So, when an outsider, even a student nurse comes in, they’re alarmed by what is going on. But those of us on the inside might not even hear ourselves. And I think culture is so powerful. I mean, it came from an Awake and Walking ICU where everyone’s awake and walking and it was normalized. Then I went into a new environment and I was shocked initially, but I will never forget how normal that became to me. And I know I laughed at some of those jokes as well, because I didn’t know what patients were actually experiencing. And I almost had a new level of shock when I returned the Awake and Walking ICU. Because the culture was different. The practices were different. I had just adjusted and acclimated to that environment so much that it just became normal and I could even joke about it. I had seen patients be so successful elsewhere. And the news we had reports of these two nurses from Blackpool what was it just like a step down or a neuro nurse step down unit. And they were giving them sedatives that were not prescribed. And two sounds like they were getting so deeply that they knew that they were almost killing them. And then they were texting each other joking about it. And the texts were just appalling. But the time is really ironic because here we are watching this meme page, going up having a heyday over joking about sedation, and yet we’re seeing across the, the world, these nurses, they’re being jailed for, again, these meds were not prescribed, but part of the case was that they were joking about it. And yet, here, we’re okay to joke about it. What are your thoughts on that?

Jess Hren [00:15:21]

Well, I do want to circle back to what you were talking about with the nursing student. Because these meme pages and the impact they have on patient care and culture, that nursing student had to report those nurses. When you’re joking about these things at the bedside, you’re joking about taking someone’s autonomy and their agency and their voice away with sedation. And that student nurse didn’t feel safe to confront those nurses. That student nurse did not feel safe to ask questions. That student nurse did not feel safe. And as someone who’s super passionate about student nurses, and teaching new nurses, that is my pet peeve. I want you to feel safe. I don’t want you to feel like you are in a position where your autonomy and your voice could be challenged.

Kali [00:16:10]

You’re being taught things that are that are not evidence-based or that are harmful to patients, and that the environment in which you’re supposed to be learning. You’re not comfortable, because it’s not a humane environment.

Phillip Gonzalez [00:16:22]

I’m touching on that. I mean, there’s a reason why there’s the same nurses eat their own. I mean, being an occupational therapist working in the ICU, I’ve been witness to that where ICU nurses can as easily tear somebody down as quickly as they lift somebody up.

Jenna [00:16:40]

And I’ll even go as far to say, it’s not just nurses. I mean, I’ve experienced that as a PT and see it with OTS as well. Really just anybody that works in the ICU is, I don’t think it ever comes from a malicious place. Sometimes it might. I can’t speak for everyone, I don’t know where your mind is. But it’s we’re protective over our patients and we’re prideful in the knowledge that we have, and the way that we feel things should be done. And that translates a lot into teaching and that happened to me at times in different ICUs. And I’ve made it my life mission. Like you just to make sure that I never teach anyone that way because it’s hard, it is stressful. The ICU is a stressful enough place on its own. We need to be mindful of how we’re teaching people. But I guarantee you like these nurses that this student reported, didn’t have any, awareness of how they were speaking. They are so calloused to it and to the environment that they’re in, that they weren’t even aware of how bad it sounded. And it took fresh eyes coming in saying, “Wait a minute. What are we what are we doing here? What are we talking about?” And that’s sad, which is another reason why I feel we should be talking about this.

Kali [00:18:11]

I remember the first ICU I ever entered was as a student, nurse, and I was so excited to be there. I always dreamed of being in an ICU. And so, I got there with all the passion, enthusiasm, you guys know, I’m a chatter. So, I walked into this unit, and I think I was 19 years old at the time and this ICU nurses on a night shift. So, if you imagine, excited nurse coming into a night shift, the nurse said, “Hold on. If you think that this is going to be social hour, you’re strongly mistaken. I’m here because I don’t want to talk to people.” And that was it. That was the whole rest of the shift. That was my first hour of being in an ICU. I was told, “I, as a nurse, I’m here because I don’t want to talk to people. I work in the ICU, so I don’t have to talk to people.” Now that I’ve worked in 11 different ICUs and also consulted in 10 or more ICUs that’s not the norm. Like to who nurses are, I really don’t know that I found a lot of other nurses that would ever say that to a student within five minutes of meeting them. But I did experience in these other ICUs. I felt like an outsider because I wanted my patients to wait and in order to fit in, you had to pass initiation. There’s almost, again, an initiation into the culture of you got to be hard and you got to get with it. We just knock our patients out because that’s what we have to do and we’re going to laugh about it that the jokes are part of fitting in to the culture. Just feels like you’re about to say something.

Jess Hren [00:19:42]

I think it’s interesting. Yes, because you’re hitting the nail on the head there. Because the way you said that’s what we have to do. First and foremost, anyone listening, nursing is not a cult. I realized they may have made it sound like nursing isn’t not a cult. But there is an aspect. I don’t want to call it martyrdom that we shirk off as ICU providers. But to an extent, we are also victims. Because we have 100%, we’ve all seen some really terrible stuff. And we haven’t been given the resources to cope with that. So, when you expose people to terrible things, you’re going to force them to create their own coping mechanisms. And I think sedation became a way of mitigating stimuli. And like mitigating the things that we see but then the issue is, we’re not mitigating it, we’re pushing it backwards. We’re throwing an exponent on it and saying we’ll deal with it tomorrow. Because I’ve heard plenty of nurses say, “Hoo! hope they don’t get extubated on my shift!” And that’s also a problem.

Kali [00:21:05]

That was some of the main content as well. The frustration that they feel when the docs can make them do an awakening trial, or they start their shift off and they’re intubated, and the disappointment they throw now that they’re extubated. And I think that it is a challenge to deal with patients when they’ve been sedated. Now they’re delirious. Now they’re crazy. So, they’re trying to capture the burden and I guess the frustration is that they feel and now they get to deal with this hot mess of confusion and agitation. And I think when you say that we’re victims, I totally agree. I feel so many of us and myself included, for so long, I was a victim of this gap in knowledge. I wasn’t taught why patients were awake and walk in the first ICU and why it’s harmful to not have them that way. So, what’s the harm and joking about that, but then that made my job harder. I was deprived of the humanity of my career and I felt so much burnout. And obviously, as a travel nurse, I was going into situations that were much harder. The staffing was difficult. There were other challenges, but I became to notice that I wasn’t having joy in my career. I wasn’t connected with my patients. I mean, it was so rewarding in the Awake and Walking ICU. I knew what their favorite songs were. What food they were looking forward to eating when they were extubated. I knew who their families were. I just knew what mattered to them and I was fighting for that with them. And I got to see so much more success. Whereas elsewhere, I was taking care of decomposing zombies in the bed and trached and pegged. I never got to know them. And I think we think that that’s a coping that’s necessary for coping. It’s protecting us. It’s really not we’re victims of a dehumanized environment, and an absolute ignorance. When now when we see these memes, we see a totally different picture, but they’re seeing normalizing things that are very difficult and traumatizing, but unavoidable. And let’s talk about what this means really should say to us first, what were some of the concerns that you saw in the memes? And what was your perspective about what those actually said?

Phillip Gonzalez [00:23:14]

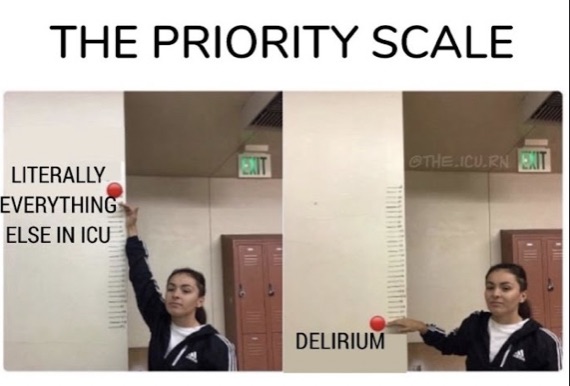

I think one of the memes it stood out to me was literally everything in the ICU is greater than delirium. I know your mission is practicing and preaching on changing sedation practices, and mitigating the risk for delirium in ICU care just because of the consequences and negative effects and the immediate and long term outcomes for ICU survivors. And though I can understand whether it be a single unit, I see a single Oregon ICU or a multi-specialty ICU, there are things that are just as important as managing the sequela of ICU-created comorbidities. But movement and mobility and the ability to be autonomous in our own decision-making if we’re patients in the ICU is just as important. Being able to be awake, being able to communicate our needs, being able to actively participate in some of the decision-making can help guide the interventions for us as healthcare providers. But also give that patient the power to be able to be actively involved. And if, for whatever reason be, there’s an indication for sedation. It needs to be understood that as healthcare providers, we are potentially taking away that God-given right to that patient. On top of that, countless studies show the risk for sedation on acute and chronic outcomes. There’re numerous studies on the risk of bedrest, on the muscular skeletal system, the neurological system, endocrine, cardiovascular, pulmonary, you name it. I mean, you’ve covered a lot of that research at nauseam in multiple episodes of your podcast. There’s again, numerous types of research out there on the comorbidities associated with ICU-acquired weakness, both the acute stage and the long-term stage. And I think you hit the nail on the head with the culture aspect. The social media pages, the influential power that some of them have, and what we have to do as healthcare providers in the ICU can sometimes be dehumanizing to the critical care environment. It can be dehumanizing for the patients themselves. It can be dehumanizing for staff or students that are coming into the ICU and ultimately, that can and does impact that care that those patients received and how we deliver it.

Jenna [00:26:02]

Yes, I think with that, I understand where that comment comes from we often hear well. They’re in the ICU to save their lives, the rest doesn’t matter. But it does, yes, we’ve all experienced the patients that come crashing and burning into the ICU. I have worked in some of the highest acuity ICUs, in the southeast of the states. I’ve seen it all and I’ve also mobilized a lot of patients. Thankfully, work in that kind of culture, but like that the crashing and burning is just a very small portion of their ICU stay. They come so that we can stabilize them. And yes, there may be stable, but still on a lot of life sustaining support for a long time while their body heals. And what we do during that time, can have a huge influence on their outcomes. Not just the minute where they’re crashing and burning and we save their life, that yes, that is very important, the most important of their ICU stay, but if they survive, what kind of life are we setting them up for? And I think emphasizing that is really important. Some of the other comments that really got to me, that I’ve seen is saying, there’s literally no research. We’ll talk about this later on. I don’t think we need to delve into it now. But there’s literally decades of research, literally decades. We can get into that further. But saying that it’s barbaric to mobilize patients on ventilators, emphasizing that over and over and over again and that like really hits me hard, like it deep in my soul. Because, as ICU providers, we have a moral and ethical obligation to provide the best care for our patients.

And I can’t knowingly not do something if I know that there is a better and more effective way to do it, that will be better for my patient. And not to mention, I treat every single one of my patients like I would want my own family member to be treated in the ICU. I teach my students that. And to say that we’re knowingly torturing someone on purpose. Again, just hits me deep in my soul, because that is everything that I’m against. We go in the medical field to help people heal. And again, at people’s side, during the worst times of our lives, and doing everything we possibly can to make them better. And so, it almost makes me emotional to talk about it. Because again, it’s just hits me to my core of what I feel my god given purpose is on this earth is to try to improve the outcomes for as many patients as possible. And that’s really driven my career and how I’ve ended up working with you, Kali.

So, it’s just really sad to see that and the misconception that that comes from, which leads into the next one that I hear all the time. Actually, saw this on a comment on LinkedIn on a video of someone walking on a ventilator, two days ago. “Well, if they’re walking, why are they still on the ventilator?” And that is such a misconception. People are placed on ventilators because they have sick lungs. And they have sick lungs, their airway is compromised, or they have a neurological impairment that is impairing their ability to protect their airway. Walking is an innate survival skill. One doesn’t go with the other. Yes, someone can have lungs that are so sick, it impairs their ability to tolerate walking. However, we placed them on ventilators to help that. So why would we not try to continue to keep them strong while their lungs heal? They’re just the two don’t go together in my eyes. I’m not saying that they’re not related at all. But I think, we just need to flip the way we’re looking at that a little bit differently.

Also, there’s just the assumption that people think that the patients that were moving are not as sick as their patients. I know that you hear that a lot, Kali, and it’s just not true. Again, I’ve worked in some of the highest acuity ICUs in the southeast, and we’re still moving those people. I’m moving those people that are on a ventilator, on VA-ECMO, on 300 trips, and two pressers, and CRRT and all the things, and every patient is different. And we’re looking at what organ systems are involved and what support is on and how can we optimize that to maintain their ability to move. And the reason that is, is because we know with research that the more frail patients are, the worse their outcomes are going to be. And especially the transplant patient populations, which is the patient populations that I work with a lot. The stronger they are going into surgery, the better they’re going to do.

Which is why we work so hard to understand these patients to make sure that we can support them enough to keep them mobile. And so, I just really wish people could pivot the way that they think about that and just because they’re on the support doesn’t mean that they need to be wasting away in a bed. And those are some of the ones that just struck me a little bit and just like some of these people that you just can’t change their mind on that. And it’s like, man, why? Why is that? Why can’t you just pivot the way you think a little bit.

Phillip Gonzalez [00:32:12]

I wanted to comment on two aspects of that. I think the first part of it is the need for a ventilator and mobility and walking are not mutually exclusive. The tolerance for that. Having worked as an OT in the ICU for the last 10 years, I don’t want to downplay the critical need for ventilators when they’re appropriate. But in practice, I sometimes view the ventilator is just an added support for the patient. Almost no different than I would use as a rehab professional using a rolling walker to support a patient in functional mobility, the ventilator supporting the patient from a respiratory standpoint to perform the tasks they need to perform. And then additionally, let’s talk about competency for a second. It takes a lot of competency and skills to be able to mobilize those patients at that high acuity stage that we don’t get in school. Some of us don’t ever see it in our practice. So, I think what Kali, you’ve done a phenomenal job of addressing some of those deficiencies and opportunities that institutions have to improve their standard of care and practice, to really be able to provide the best care for their patients.

Kali [00:33:33]

And when people say, “This is so unsafe”, I refer to these studies in which it’s been done. But I also have to remember that these were done with teams that were competent, that it had that training that culture, that interdisciplinary teamwork to make it so safe. So, as I go to train teams, I have to remind myself that we’re building that kind of ecosystem, did not have expectations for these clinicians to have that kind of expertise if they’ve never done it themselves.

And these memes actually helped me understand a lot of the fears, the perception, the culture, the perspective of many of our ICU clinicians, so that I can address those needs and those gaps in knowledge. When I see the jokes about the RASS, I think, not that they’re bad nurses, not they’re bad people. But that, “oh, they don’t understand. They don’t know that when patients cannot lift a finger, that that’s an independent predictor of mortality. Oh, they don’t know that, we should talk about that. Oh, they think that patients shouldn’t be awake until they’re ready to be extubated. And that it doesn’t make sense for someone to be walking, awake on a ventilator. We need to talk about that.”

So, I think we should take these insights and use them to guide how we approach our teams and make sure that those gaps are filled that they have the knowledge they need to see what we see when we see this content. I think them joking about oh, we’re in decreasing mortality. We are giving them a brain injury or taking away their ability to walk. It’s so funny. But that’s not where they’re coming from. But that’s what we can’t help but see that they’re joking about.

Jenna [00:35:11]

Right. And I think, on that, the assumption that we’re just dragging every patient down the hallway, that’s not true. You’re meeting the patient where they’re at? It depends on their support, it depends where they are in their illness. Are they in the acute phase? Are they in the maintenance phase? Are we in the healing phase, and kind of meeting where they’re at and some colleagues of mine did a phenomenal presentation at CSM, the APTA conference about how do we assess that, because we’re not taught that in school. And yes, if they’re up trending, on all of their inflammatory markers, and all of that, they may not be appropriate to walk down the hall. But there is still something that we can do for them that may be beneficial, and just getting up right, and helping their lungs clear and all of that things. So really, emphasizing the competency aspect to help us assess our patients and what they need specifically, and not just doing it just to do it. That’s not what this is about, making sure that we can really do what each patient needs at the best time for them.

Kali [00:36:26]

But that level of customizing care is not a norm. We are again victims. We are sucked into this process of which is the conveyor belt. So, they’re not taught how to think through each individual patient, or each day, or each hour for that patient, or how the status may be changing and why we should be mobilizing them and why stations, like the whole thing is just unknown to most of our clinicians. And then they get to deal with the mess that it creates.

Jenna [00:36:57]

And not to mention, all of the staff, not just nurses that have come into the field in the last couple of years during a literal staffing crisis, the training and the quality of that training compared to those of us that are were trained to pre-pandemic and could really take time to things, it’s just a different world. And now we’re paying for that on the back end.

Kali [00:37:21]

And they’re also stuck in the process of care in which patients end up spending days, weeks longer in the ICU, and not thriving. They’re hard patients to take care of. They’re a lot of work. So, it just adds to this burden and this burnout. So, I think when I see these memes, I also feel so sad for them. But that’s how they see not just for patients but their careers. And that’s to me not what Critical Care Medicine is about. I also was reached out to, by a lot of survivors, future patients’ family members, that were saying, “Have you seen this?” or “Do you see what’s going on? This is so upsetting.”

They were terrified. They said, one, “They’re making fun of my trauma. This is very triggering. They’re laughing about one of the most life-altering and traumatic events of my life. Is this really how nurses feel or I could end up back in the ICU? What if it’s a nurse like this, it’s taking care of me?”- which just killed me, because that’s not how I see nurses and that’s not how I want nurses to be seen. Jess, what are your thoughts about that?

Jess Hren [00:38:28]

Yes, I do want to hit on that. And I know some of the things that I’ve said may sound like I am vilifying nurses or we are not taking accountability for what we’re doing. But Jenna, you said, you pose the question why won’t you change your frame of mind? Why won’t you change that thought? ICU nurses specifically are taught that every single thing that happens to a patient is our fault. If the ceiling is leaking water onto their forehead, if the room is too cold, it is our fault. And we are expected to take accountability for those actions.

We have a vast gap in our knowledge base about sedation. And I remember Kaylee and I’ve talked about this in the past, and I’m sorry for if this is triggering to any nurses that may or may not be listening to this podcast. But we were said contributes to or if not directly causes renal failure. And I remember during COVID, I would have patients on turnover said 50 propofol 200 of fentanyl and I read a paper like that. And I remember I was home alone and I thought to myself oh my god, I did this. Because I remember the names of most of my COVID patients from my very first job that I violently overstated.

And I know the nurse who made that meme page probably doesn’t listen to this podcast, at least not religiously, but if you do, I want you to know that it’s not your fault. You’re doing the best you can. There is new information. And just because there’s new information doesn’t mean you’re a terrible person for not having it immediately, or not having the resources to utilize it.

Jenna [00:40:26]

I think, for me, the reason I’m so passionate about this is, I have taken care of countless patients that have literally wasted a way to the point to where they can’t lift a finger. And that’s our job. That’s mine, and Philip’s job is to rehab these people. And I think that’s why it’s so close to chest for us. Because like you said, think of their names of the ones. And the ones that I remember the most are the ones that made it. The ones that I literally would sweat my butt off trying to rehab so that they would qualify for transplant or so that they could get off ECMO, or make it out of the ICU. And what’s sad to me is, I’ve thought about this a lot over the last 24 hours, and as we prepare for this content is, “Why can I not remember the names of all the ones that didn’t make it?”

I think it’s because we cling to the success stories. But there’s countless ones that were so sick, and so wasted away, that they didn’t make it, that they ended up dying, or going to attack and then dying from an infection later on. And I think that is what made me fight so hard to see the other side of it, and to really dig into the research. And it really wasn’t until I met you, Kaylee that I really realized that this stuff could be avoided. Not always, I feel the pandemic is a little bit of an exception, where some people were so sick, that they had to be on paralytics, so that they could oxygenate their body. We’re not trying to not look at those patients, too.

But majority of the patients could have been avoided the level of weakness that they’ve had. And it’s just sad to think about Filburn, I had the pleasure of getting to do a panel discussion with a patient that we treated during COVID, who we rehabbed from barely being able to lift a finger off the bed to walking home from the hospital, getting a lung transplant, getting off ECMO, and walking out of the hospital and going home. And that is not the norm with that level of patient.

And I got really emotional during the panel discussion, because we never get to see that. It’s rare that us as, ICU providers, get to see them walking out of the hospital and going home. We only see the sickest side of it. And that’s why I do this. That’s why I fight for these people. And even their families, because we spend so much time with them in the ICU while we’re with them, even their families were close to. But we don’t get that luxury with every patient. So, I think, gotten on a tangent here, but just remembering that there is a human behind it, even though we don’t always get to see that.

Kali [00:43:42]

But as therapists, you’re programmed to focus on that aside of it. What happens after the ICU? And where are they going after the ICU and how are they getting there? So, walking home from the ICU is your ultimate goal and even if patients don’t achieve that you make such an impact to have them eventually end up there or leave at a higher level. But as nurses, were not trained to think that way. I can’t remember at what point someone said, Well, I just tried to think of the patient’s baseline. And that’s when I realized, I don’t think that was part of my assessment. As a nurse, as a nurse practitioner, I had to understand a little bit more but as a nurse, I wasn’t saying “This is a 52-year-old welder that was walking and liked to golf at baseline.” I didn’t think about it that way. But it was the therapist that taught me. That’s who I’m treating, and that’s what I’m getting them back to. But nurses we’re not. That’s not our focus. We’re like I’m just here to put up the immediate fires.

And so Jess, I’m so touched by your example of being receptive to new information. Yes, you were out to disprove me but you went to the right sources. You dug into the evidence and you were at least willing to see that what you’ve been taught maybe wasn’t what should be done. But that’s a really hard thing to do that requires a lot of humility.

Dr. Murphy, I can’t remember which episode talked about, having been an intensivist for almost 50 years. Hearing this information, scoff at it, but still remained open enough to consider the possibility that he was harming patients. Dr. Ely, in his book, every deep drawn breath talks about that process of recognizing that he was hurting patients. And using that, I guess we could consider guilt, or that pain, from that acknowledgement, to spur us in to doing better for our patients. And that’s what I hope for this podcast. This whole mission is that we don’t sit there and feel bad about ourselves and think, “This is all my fault that I killed patients.”That’s not the objective here. But just to be open enough to recognizing the harm of our current practices, enough to spur us into revolutionizing and moving towards the future.

But when I had personal interactions with this individual who has an anonymous page, they clearly want to be anonymous, but when I interacted with them, there was no possibility of acknowledging anything that we’ve just talked about. And rather, their responses were very toxic, very defensive. I think they might really believe when they say that they are a patient advocate. They really saw me as the villain as far as I was advocating for inhumane practices. Then you may have patients awake, it’s inhumane to have them walking. And I was conflicted. I don’t know where they are at. I think they’re in a tough spot. I can tell that they have a lot of trauma, a lot of personal issues going on. So, I don’t think they represent the ICU community as a whole or ICU nurses, especially. I’ve met with thousands of nurses now. They do not represent nurses as a whole, but it did expose a lot of the trauma, a lot of the knowledge gaps, a lot of the things that burden our nurses, and that makes me feel very defensive.

But there were things that they said that were just really upsetting to survivors, “They were making fun of my trauma. Sedation was not sleep. It was not peaceful.”- and the response would be, “Did you die? But did you die?” And almost it reinforced this whole belief that we have to do things to save their lives, instead of saying, you know what we did, actually increased mortality and morbidity.

So, I just was really grateful for this ICU community. Many people were jumping in and trying to comment and really trying to engage and educate this individual who was not receptive. They would tag me in it saying, “Hey, you should check out this page!”– which incited her more. And so, I think that’s really what made me a target, which is fine. It was okay, if you feel free to tag me in anything. But the level of defensiveness and hatred was astounding. You know, initially, it hurts, it feels personal. I mean, I guess it really was personal. I have thick skin, but it was…. Everyone’s nodding their heads, “yes, Kali, it was personnel, don’t be oblivious.”

They were posting my full name and my license number encouraging everyone to report me to the Board of Nursing. And certainly did report me to the Board of Nursing themselves. I’m not sure how many, if anyone els, ended up reporting me. Of course, nothing came about it, because you don’t just report to the Board of Nursing and someone’s license gets taken away. There has to be reason. And because there’s so much evidence to support this, this is best practice. I don’t think that the Board of Nursing really did much with it or took it seriously at all. So, there’s a whole process.

But they were also reporting me to the CAN. The American Association of Critical Care Nurses. Which was a little ironic, because the AACN ahd me present about this at NTI and they post about things with about the ABCDEF bundle and about teams that are walking their patients. So, the irony was a little bit funny that I was reported to the organization that fully endorses everything that we’re sharing. So, I wanted to do this episode to bring these things to light to have everyone weigh in on it. Because this is not just me defending myself to an online troll or bully. Yes, it was very personal but I think I was able to quickly get over that and see that this was rooted in a lot more that did have nothing to do with me. This is not just a nursing problem, either. Like Philip and Jenna have said, this is a whole entire culture that we’ve been fighting.

And again, I consider myself part of the problem, at least in the past of joking about these things. I was part of those jokes. I would have probably shared those memes with my coworkers, eight years ago, 10 years ago. I again would have laughed at those things, but knowledge is power. So, let’s look through some of the misinformation that they shared because there was a lot. And it wasn’t just because they were saying it, I think a lot of our concern was people were engaging in this. It was being shared in the thousands.

There were lots of comments that she’s sharing her stories of other people reinforcing a lot of this bad culture and absolute ignorance. So, let’s break it down. One of the things that they had reported me for was something that I was advocating for “unsafe and unproven modalities”. And they used the TEAM study as their evidence and their “gotcha” saying that this is a very dangerous practice.

So, you can go to Episode 117, where we talk at nauseam about the TEAM study with the author the team study, and with Dr. Wes Ely, and Heidi Engel. But ultimately, that study did not disprove mobility. It was basically said that 12 minutes more was not enough to rehabilitate patients, after six minutes of or six days of arrest, negative three. They did show more adverse events, but there was concerned about reporting bias. But also, we know that we destabilize patients with sedation and immobility.

Also, can’t help but mention, Sabrina Eggman put out a really great article about in The Lancet about how we need to be categorizing adverse events that they’re not all the same. Some of these are physiological responses to distress or to exertion. So, this was not any kind of grounds to disprove mobility or to get me in trouble with the Board of Nursing. What are your thoughts on that?

Jenna [00:51:33]

RASS of negative three? How can that be classified as early mobility, that patient is not actively moving themselves.

Kali [00:51:41]

So, they took a break. They take a break first. They took off, turn off sedation, mobilize them and then started sedation. So that’s mobility, right? Wink, wink.

Jenna [00:51:48]

Of course, things are going to go wrong during that. I just can’t imagine how sloppy that looked. You know, we’ve all been a part of those mobility sessions where the patient is delirious, or they’re barely awake. I’m sure it looked as terrible as we’re reading it on the paper. And not to say that these clinicians did a bad job, we really need to define what we’re doing. And I think if you read the entirety of that article, you would see that. And also, just along that, I don’t know what this person in particular, or anyone that doubted what we’re trying to push, what hospital would let you in the door. If there wasn’t a ton of research and evidence to support what you’re promoting. They’re not just going to blindly let you change practices at their hospital without evidence to support it.

Jess [00:52:52]

Right, and they go ahead, Philip.

Phillip Gonzalez [00:52:54]

To add on to the TEAM study. One of the biggest things that we often hear, especially in the rehab world at all, it proves that rehab isn’t as crucial as it is in ICU. The thing that I like to mention about that is the control group for the team study still had a pretty high level of early mobility practices already established. So, it isn’t a matter of early mobility doesn’t work in the ICU. It’s a matter of what quantification of more early mobility gives us a representation of beneficial outcomes. Now, we cannot discuss at nauseam that methodology and if it actually proved what it intended to prove. The author herself is still a huge proponent for early mobility practices. I don’t think the results were what they expected. But I also believe now, and I suspect that they also can contribute some of the reporting biases due to differences in early mobility practices across all the institutions that participated in the study, the differences in reporting in sedation levels, and then going back to we talked about the competency levels of the clinicians actively involved in the study.

Kali [00:54:21]

And there wasn’t much of a contrast between the groups. So, it makes sense that there wasn’t much of an impact noted with only 12 minutes more. And yes, many have said this is a higher level of mobility than my ICU is doing. And so that study was misinterpreted not just by one nurse online, but by so many clinicians. Since that study came out almost every team I go to, someone brings it up, usually a physician saying, “Well, now we know from the team study, mobility does nothing.”- and it drives me up a wall.

So, when they brought that out to say, show this study to the Board of Nursing. It honestly, they just made me laugh. Because they clearly only looked at the last two sentences of the abstract of the conclusion, and found what they wanted to see. And so, when we don’t really look through this research, we don’t have the tools to discern the research. It’s easy to fall into those traps of confirming our own bias. And so, it all made sense to me why we use a couple of research classes, even in our bachelor’s programs, right? My perspective of research has changed but I appreciate that we’re not all going to look through the research and look through that. So just something to be aware of that I think the teams that he’s brought up in a lot of different contexts, combating a lot of our different revolutionist efforts. But there’s so much more to it. So, go to Episode 117. Go to Heidi Engels episode just recently on early mobility, we need to be prepared for that. So, I thought that brought up a good point of yes, the study said what it said, but that doesn’t mean it needs to hold our efforts back.”

Also, on the topic of bias, I know I’m bias. So actually got excited and invited them to come on the podcast to share their concerns and discuss the research. I also invited another naysayer physician on and both the RN and the MD disrespectfully declined. So… I’m still open to bringing opposing perspectives to discuss their views and any evidence onto the podcast. Let me know if your’e that person or have such a willing person.

Another thing that they were sharing was a video that I shared from Brazil, where a patient is playing “volleyball”, I put that in air quotes. They are standing there swatting a little balloon across a piece of tape. And they were saying “This is so unsafe. Look, Board of Nursing. Look what she’s sharing. She’s advocating for this one.” Lots of other doctors have shared that like Paul Wishmyer. They’re not reported. But they’re playing out this volleyball is that they’re spiking and diving for an actual ball going at high velocity against the patient that’s intubated. And so, what are your thoughts on what is safe and appropriate for mobility in the ICU? Why would this team member dare to have them plain quote, “volleyball”?

Jenna [00:56:44]

I think Philip and I were talking about this yesterday. I like to dive into a therapist brain here is not everything we do is just walk patients. You’re looking at every aspect of their movement and analyzing it at each joint, trying to decide what’s functional, what’s not what needs work, and playing in their respiratory system, how their cardiac system is tolerating? We’re looking at the whole picture. And sometimes it’s not appropriate to walk patients. What if that patient didn’t walk before they were on the ventilator, but they were able to stand and get to a chair. Or what if respiratory, the respiratory therapist isn’t available to help me make my ventilator mobile, so my patient can walk in the hallway. That’s the case a lot of the time.

We work in a staffing crisis. And so, we try to really be creative to help our patients get better, but also enjoy what they’re doing. Rather than just sitting in an ICU room, staring at the wall for days at a time, trying to humanize it, make it more fun, entertain them, and also make it purposeful for them. So just not fixating that this patient is playing volleyball, they’re doing something likely that the physical therapists plan to be extremely functional for this patient. And playing volleyball and having to do upper body movements is a lot more than just swatting at a balloon. It’s taking a lot into account and I myself have done these many times with the patient at bedside, just sitting on the edge of the bed or standing in the room. So, I think you just again have to turn your lens a little bit and try to think of it from a different perspective.

Phillip Gonzalez [00:58:31]

I think without knowing context of that patients or persons diagnosis or anything like that, just looking at the video itself. As a therapist, they’ve obviously demonstrated the functional skills to be able to tolerate prolonged standing. They’ve demonstrated the coordination and motor ability to know what’s safe. That therapists are obviously trained in early mobility practices and ventilatory management and patient handling skills. So, from a clinical reasoning standpoint, that activity alone is beneficial to that patient for numerous reasons that Jenna just outlined. But I also look at it as it from an OT standpoint.

There’s a component of their occupational profile. And we touched on the first episode that I did with you, Kali, and you mentioned it a little bit early on in our discussion today of looking at the patient as a whole, looking at their baseline, what is the goal to return back to, after this critical illness? And as an OT, a lot of our assessment delves into a patient’s occupational profile. What were their tasks that they have to do? What are the top things they had to do every day to take care of themselves? What are the things that they enjoy doing? What are some extracurricular activities they give their life meaning. They give their life joy. And those are all important factors that we consider as therapists. I don’t want to just say pigeonhole it and say it’s just OTs that do this because we work with phenomenal to take those factors into account too. But it allows us as rehab professionals the opportunity to humanize that critical care and make their rehab more enjoyable by doing something that they had previously enjoyed doing, and also allowing patients to see that proverbial light at the end of the tunnel and see a hope for a better quality of life as they’re recovering through their illness.

Jenna [01:00:29]

With kids in the ICU, all kinds of things with children on ventilators and ECMO and all the things, what’s different with an adult?

Kali [01:00:39]

I remember in COVID, there was a patient that was very despondent. I think there are so many reasons for them to become severely depressed. I think, obviously, COVID is neurotoxic. They were just kind of seeped into this depression and no family there, and they just stare at a wall, right? So, this patient that was so despondent, would barely communicate with anyone. He was intubated, because sit up in a chair. He could walk around, he was functional, but he just wasn’t there. And I thought physical therapists walking in with a bedpan and a cane. And I said, what are you doing? And she said, we’re going to play golf. He loves to play golf. And it just hit me so deeply, because I just seen him as, oh, the depressed COVID guy in room 52. Especially as an NP and it’s an isolation and there’s so much going on. I just didn’t have a connection with him but the PT did.

And she really dug into what is he like, what’s going to matter to him and it was golf. So, what did she have at her disposal, a bad parent and a cane. I just thought she was really personalizing care and that changed my perspective. And I think when I’m telling teams, when PT, when OT, when you learn those things about patients, write it on the board, help us as nurses, as NPs, as MDs, help our team, the rest of the team understand that they liked this kind of music, that this is what they enjoyed UCLA therapeutic benefit. You’re looking through all the muscles that they’re using, and all the things but that’s not the rest of the team’s expertise. But that’s what you see, when you see the video. The nurses are like, “Oh, they’re going to self extubate.” That’s our concern.

So, looking at it through a different lens, really can change how we not just view those kinds of videos, but how we view our own patients and our own care. There was another video of a patient that was intubated in a pool. And they said, there’s no evidence, this is dangerous, well. There’s a whole study that video was from an actual study that was done looking at intubated patients with aqua therapy, or hydrotherapy. So, it was just the irony of there was no evidence. No evidence that was constantly the claim that this is not in the research. But this person did not do any research. There’s nothing that they could try to disprove any of this.

One of those claims, especially, was there is “no evidence to support that sedation impacts vent days”- which made everyone’s jaw drop, because you have from Dr. Kress in 2000 that awaking trials alone decreased spent days by 2.4 days. Dr. Strom in 2010, published a study showing that having no sedation decreased spent days by 4.2 days. I mean, that evidence showing that sedation absolutely impacts bed days, but that was their claim.

And the scary thing is, it’s fine if one person is saying that, but the fact that there were thousands of people rallying behind this. Nurses that were believing this. I worry about the new nurses that are like, Oh, look at this cool funny meme. Oh, my goodness, look at all this information, this controversy. And they were believing them. Do you think Jess that that was believable for other nurses?

Jess [01:03:44]

I believe, believable is not as important as validating. So, I don’t think that it made things believable. I think it validated. I’ve told you before about my experience with patients who’ve been on long-term sedation. There was one guy I literally had to go every time I went into his room, my coworkers were pregnant, there were a couple of them that were older. And he was known for getting violent because of his delirium. And I would wear a mouthguard, every time I went patient’s room, and I laugh about it. But I’m like, “Oh, I do still have a chipped tooth, battle scars, but those, we don’t want to think that we did that.”

We don’t want to think that he is fighting off of his worst beers because of something that I did. And I it just because if we acknowledge that we played a role in that, there is so much in my career, that I would have to live with. That I would be very, very uncomfortable with. And one thing that I would really strongly encourage nurses to do, therapy, love that, hey, Bri, that’s my therapist. She’s been doing great work. But she wanted me to surrender some of that responsibility to my physical therapist, to my occupational therapist, to my personal therapist, which by the way, I work with one right now.

I know we do a journal study on this podcast, you’re great, thank you so much. Because in that patient’s entire outcome does not depend upon you. Trust the competency and capacity of your teammates. This is a team. The reason we wanted it to be validating, is because that makes us feel safer in only trusting ourselves. That makes us feel safer in isolating that care, only to us. And at the end of the day, nurses really do drive this ship and most hospitals. We are the ones who say that physical therapy and occupational therapy, can go see that patient. Let them try.

Kali [01:06:06]

That’s not how it should be.

Jess [01:06:09]

But good grief, let them try. What is the worst that is going to happen? I don’t have a mouthguard for you. But go, give it a shot. Playing Rock and Sock and robots counters physical therapy. You know how much energy they use to extend that right hook? He is going to nap, naturally. So well after kicking my butt for 20 minutes.

Phillip Gonzalez [01:06:36]

I think to your point, Jess, the ICU is a team sport. We’re in it at the team. And I mean, I’ve joked about other healthcare professionals that I would trust treating myself or family members or other therapists that I would trust treating myself and cared for family members. But ultimately, providing patient care in the ICU isn’t a singular entity. It’s the physicians, it’s the nurses, it’s the therapist, it’s the nutritionist, the dietitians, a pharmacist. It is a true interdisciplinary environment where you have to be able to trust your other team members to be competent, or be able to help advance their competency skills in the ICU. But on top of that, because it is a team sport, because it is an interdisciplinary environment, no singular entity should share that responsibility of those patient outcomes.

And I think you bring in up that point of your therapist, advocating for you to offload some of that shared guilt or some of that guilt is a valid point. Because as a therapist, I feel that same way on patients that had not done well in ICU and their rehab aspect. Did I do enough? Did I advocate for them enough? Did I use the best interventions? For those patients that didn’t make it? Was there something I did wrong? Was there something I could have? I mean, those are all stories that we tell ourselves as ICU providers day in and day out when we’re providing care. But ultimately, it’s not any one individual’s responsibility to take that burden on. We’re an interdisciplinary team and we have to be able to trust our team members to manage some of those burdens.

Jenna [01:08:42]

I think something I want to talk about that, being a team sport, part of that team members, which we haven’t highlighted yet is the family members. They can be such a pivotal part of the patient’s care in humanizing it. Like, what does this patient like? What kind of food do they like? Nutrition is a whole another aspect. And they’re in pain, what pain medicine usually works for them? Or if they normally have back pain, what position works best for them? Okay, they’re confused. What’s some things that we can use to orient them from their normal environment. Sometimes just a normal voice they recognize can be helpful. And I think there’s this big, I guess, misunderstanding about family members being in the room in the ICU, because we’ve all dealt with those family members that are extremely difficult. And we’re all calloused to what we look at on a daily basis in the ICU, and a lot of times family members are just reacting to what they’re seeing in the room and sometimes we just have to explain things to them. I think it’s just we have to remember that. And sometimes the family just needs a little education and attention to.

Kali [01:10:07]

A lot of the memes, not a lot, but some of the memes were focusing on having family gone. The ideal patient is to be “sedated, paralyzed, and family gone”. That’s the bread and butter for the nurses and I don’t see that as so much easier, maybe for that one shift. But when you’re validating this culture of, I take full responsibility, I have full control over everything. You’re making your job so much harder as a nurse. So, I see that night, I hurt for the nurses. If you think early mobility is dangerous, you think physical and occupational therapists are not important in the ICU, that there’s not a priority early on, that it comes down to and the family shouldn’t be at the bedside, or that they’re just a nuisance, then yeah, it really all comes down to you.

So, we’re complaining about not being supported. Yet, we’re depriving ourselves of the support that’s available. And so, then it becomes, obviously this huge mess to do awakening trials, to take off sedation, that’s masking the delirium that sedation is caused. And then it comes down to just one nurse to have to deal with that hot mess and stead of preventing the harm, preventing ICU delirium, ICU-acquired weakness, and the whole mess, but also, we’re not calling in our reinforcements, and our teammates, to intervene with those situations. No one should be getting hit and hurt. I feel very strongly about that. But like just mentioned, a lot of that was rooted in sedation and the delirium, it caused that mess. So, we’re minimizing that, and one of my favorite things in hearing back from these teams that I’ve trained is, things like this is so much easier. Hearing that from nurses makes my heart sore, because I absolutely empathize with the burden and the trauma and even the physical and mental emotional abuse that they receive from patients. That is not what we want.

Obviously, you’re going to have patients that are just terrible at baseline or that get delirious no matter what. But that will not be your norm when you have an awakened walk in ICU. And when you have those patients, you have teammates, and a process of care that supports the nurses, and keeping those patients safe and helping them succeed and get out of that. But these memes, just reinforce this. We’re nurses, we’re soldiers, we take control the whole situation, we control our patients, we kick out our teammates, we kick out the families, because we own the show. That makes everyone’s job so much harder, and the patient outcomes terrible.

And then some of their definitions of early mobility. One person said, “I’ve been a nurse for 20 years. Early mobility is a passive range of motion, bed to chair, and I’m most pulling them over to a cardiac chair and setting them up upright”. So, what are your thoughts on that?

Jess [01:12:50]

Mobility is what they can do. And I do want to like remind the nurses of that is that you got to meet them where they’re at. And physical therapy is not going to ask your patient to run the Boston Marathon. They are not going to be in there doing the cancan. Like it is what they can do. And then I know, we’ve got a lot of cardiac happening here and we’ve got a lot of cardiac experience. Going back to the team study, talking about arrhythmias.

I have had times where I can guarantee you my heart rate was higher than my patients, trying to get them out of bed and Jenna, Philip, you know what I’m talking about. where you’ve got the nurse behind the patient on the bed, on her knees, holding them up in physical therapy. So, you’re doing great, let’s get your feet underneath your knees. We’re all sweating buckets. It’s an isolation room. I’m tacking in the 160s patients sitting at maybe the 120s, but we see those numbers. And we’re like, oh, arrhythmia. Half of us can’t walk up the stairs to our unit. Stop holding our patients to a higher level of accountability with their heart rate than we hold ourselves to.

Jenna [01:14:06]

Yes, just remembering what normal? What’s a normal response and why are we considering that an adverse event? Like your events going to alarm when you’re moving if they cough or like things like that. And anytime the vent alarms, they classify it as an adverse event. I think talking about that is always important, like you talked about. And yes, they may be tacky, but is it really an arrhythmia? And why are we fixated on that? What’s expected versus what’s not expected and just being able to recognize that going in the room. But going back to the early mobility is again, it’s very poorly defined. And your early mobility should be, what you said, what could my patient do normally? What would they be doing on a normal basis? But my favorite part of the memes is, I’m sure they do these things with ECMO patients, but this is different.

It’s okay to do it with the sickest patients that exist, who should otherwise not be alive. But my patient that is on a ventilator for COPD exacerbation, shouldn’t be doing this. Also, it’s one thing if they have a trach, but this is unimaginable, and so dangerous with an ET tube. Have you ever been in a situation where a trach is dislodged? It can be even more of an emergent situation than a re-intubation because there’s risk of permanent damage. They can bleed. There’s a lot of stuff going on in the neck area that you can really mess up, if you dislodge a trach. And it just pop right back in there all the time especially if it’s a fresh one. So, mobilizing with a trach can be just as dangerous. But again, it goes back to that competency level. Making sure your team is in place, making sure that you are competent, and confident in what you’re going to do. I can talk about this for days.

Kali [01:16:08]

That was the perception, that’s early mobility as a cardiac chair. It is mortifying? That’s where we’ve been at?

Phillip Gonzalez [01:16:15]

Well, I think it comes down to like I Jenna mentioned, and we sprinkled throughout this entire episode is that early mobility in the literature is not defined, well. Some institutions, that doesn’t mean pass a range of motion cardiac chair only, whereas some institutions, it’s awake and walking ICUs. I think what opportunities we have as healthcare providers and those looking to do further research is to really hone in on what that early mobility definition could look like. And be able to quantify that umbrella term into more specific details, so that we just have more validated data on what works and what doesn’t. But to add on to what Jenna says, one of the reasons why I love ICU rehabilitation as an OT is that it allows me as and the patients to feel empowered in their own care. To be able to see those small functional improvements when they’re at the sickest of the sickest.

Jenna and I worked together previously, clinically. And we also have both have our own separate clinical experiences before working together. And thankfully, I’ve had opportunities to work at some of the highest acuity institutions, as well as some institutions that just didn’t have the support systems in place in their ICUs, to be able to really implement an early mobility program. That was effective and that’s the reality of where we’re at in healthcare in general in the United States is some institutions have the support systems in place, and some don’t. But it doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t be able to at least try something. The reason why we’re all skilled clinicians, is because we’re able to clinically analyze a situation determine, what’s appropriate. Determine what benefits out, weigh the risks, what risks outweigh the benefits, and where can we meet in the middle?

It doesn’t always have to be zero to 100. Right off the bat. We can always just as we titrate, just as nurses, titrate pressers, we can always titrate that mobility to meet that patient’s needs. And I think you said it best just is that what work can we meet the patient at their functional capacity, and trusting your team members to be able to help you determine that, is an important part of ICU care.

Kali [01:18:34]

And that leads us to get off the conveyor belt. When we define early mobility as passive range of motion or cardiac chair, it keeps everything on a conveyor belt. Which is nice for us in a sense that we don’t have to think through it. It’s very predictable, just pop them the chair or the bed in a chair position and we check off early mobility. But that’s not customized and optimizing care for each patient.

And you mentioned Philip the status of the care in the United States. Yet we have this huge pride in having the best health care in the world, I don’t know exactly where that comes from. Because I don’t know that that’s really been proven that we have the best health care in the world. But this page was saying, “This is only done in Brazil. These videos are all from Brazil”- which is absolutely not true, but many are from Brazil. And I share those who say, “Hey look, other parts of the world are doing this.” So, someone said this is a little bit xenophobic of them. To say it this is from Brazil, therefore, it’s not a good thing. That this is barbaric because it’s from Brazil, which drives me up a wall.

My point was, even in these other countries and sometimes some of them with far less resources. I post videos from Mexico, from Ecuador, which do not have first class, first world resources and yet they are still doing these practices and I think almost because they don’t have those resources, they have the necessity. They can’t just send them off to LTACH to rehabilitate. It’s all down to them. So, they’re going to really be motivated to prevent that harm. What are your thoughts about the international picture of this? Is this really only in Brazil?

Jenna [01:20:15]

I mean, me personally, I’ve had patients or not patients. I have had patients and family members reach out to me, but also practitioners from Germany, Austria, France, Japan, United Emirates, Abu Dhabi, Australia, Mexico, Brazil, of like, one, we’re doing these things, how can we get better or we’re having this this problem? How could we fix it? What would you do? What are some of the resources that you use? Can you share this research? So, it’s not just in the US. Its people doing it all over. And people are craving it, because they’re seeing the outcomes from it.

Phillip Gonzalez [01:21:03]

As being a member of society of Critical Care Medicine, I’ve had the opportunity and pleasure to listen to one of the pioneers of early mobility, Chris Perme, at least from a rehab space. She helped really guide therapists early on in rehabilitation practices in the ICU. But as part of the ICU liberation mission that they did in Ukraine, she details a wonderful experience of being able to train hospitals and ICUs, over during wartime, been able to promote ICU liberation, awakening trials, spontaneous breathing trials. What steps needed to be in place to be able to successfully activate patients, to mobilize these patients? What training skills need to be in place? What resources needed to be in place? And one of the things that stood out to me during her presentation, during our conversations with her is the practitioners over there stated, and I quote, that “this is magic”. Because they were able to see the successes of an ICU liberation bundle of being able to get their patients up and moving in and out of ICU faster, being able to reprioritize and reallocate resources that were previously taken by patients who may or may not have needed them at the time, to ultimately better their standard of care at the institutions that she was able to be a part of.

And I think that’s something to call out, because critical care is critical care. Whether it’s here in the United States, whether it’s in Mexico, Brazil, Ukraine, Australia, Germany, critical care, medicine, is critical care, medicine but resources change, culture changes, countries changes, payer source changes, that can be a whole other episode in itself. But the mission is really to ultimately better the standard of practice for critical care medicine. And that should not change just because of a lack of competency or a lack of unfamiliarity with what best practices are.

Kali [01:23:18]

And Episode 55, there are I think, 21, 22 countries represented in the episodes titled Walking Around the World. I got audio clips from people throughout the world that are walking patients on ventilators. So, to say, I’ve never done it in my ICUs. Therefore, it must not be possible, no one else must be doing it. Or if they’re doing in these other countries, it must not be best practices is such an egotistical thing to say that we really should be looking at what are other people doing? How can we help influence other countries and other places to do best practices or what can we learn from them?

And I think being open to new ideas is a huge theme throughout this whole discussion that we saw, exemplified in this example with this meme page. They also said, when I shared the Polly Bailey study from 2007.” Well, that was just a nurse.” I think she was a nurse practitioner at that point. But the fact that they would discredit this research because it was from a nurse or from someone in the nursing discipline, was amazing to me to demean your own discipline so severely. Jess, where does that come from?

Jess [01:24:36]

Choosing my words carefully. I think it’s coming. I keep coming back to this idea of needing to construct our own reality. So that that reality reflects us as heroes and reflects us in our current practices as heroes. Right. It’s not about discrediting a nurse. It’s about discrediting anybody who challenges the idea that sedation is sleep, that sedation is therapeutic in any way. The second that that idea gets challenged. You are challenging the hero narrative of nurses, because we’re the ones who hang the sedation. We are the ones who titrate the sedation. But it’s interesting to me because this user who has been spewing all this content. One, not from the States, but I’m not going to hit on that too hard. Two, also touts the autonomy and the decision making of ICU nurses.

My mom has referred to ICU nurses as the kids you leave at home on vacation, and tell them don’t call me unless the house is burning down. Here’s money for food, here’s money for the bills, whatever. Just don’t call me unless someone the house is burning down or someone’s dying. Which is literally what we do with our physicians. We don’t call them unless someone’s dying. But like, how do we have this level of autonomy? If we can’t challenge the current research, if we can’t perform our own research, and in it, we can’t just do it when it’s convenient for us, we can’t just do it in the context of the team study so that it supports things that make us feel good about ourselves. We have to challenge ourselves in our current ideas.

Kali [01:26:25]

And nursing is an evidence-based discipline, all of our disciplines are so for not practicing evidence. Are we practically at the top of our own scope and license? To that they also said, Oh, well, that wasn’t in the New England Journal of Medicine. I mean, this was a huge fixation that the team said it came from the NEJM. Yes, obviously, that is a very high, highly influential, highly credible journal. But discrediting any research that didn’t come from the New England Journal of Medicine was appalling to me. Which I think we don’t have to dive into a ton but that was just insane. There was also this instilled fear of losing your license, because you’re mobilizing patients that this was a risk to our license. Someone on LinkedIn said, not providing early mobility should be malpractice. Do you guys feel fear of losing your license when you’re mobilizing patients?

Jess [01:27:25]

I feel, I, first of all have malpractice insurance. But second of all, I feel more fear when my patients die from my license, because nobody sues if they make it out. And people who are sedated, people who are immobile, they’re the ones who don’t make it out.

Kali [01:27:54]