Despite their widespread use in the ICU, decades of research have proven the risks of immobility and sedation.

And as clinicians, it’s easy to approach care as a robotic conveyor belt instead of focusing on the individuals, families, lives, careers, and futures that are being affected.

But in reality, ICU patients are being harmed, having their lives turned upside down, and even losing their lives as a result of prolonged sedation and immobility, which are both considered “normal practices” in the ICU.

The ABCDEF Bundle should guide us to minimize and even eliminate the risks of immobility and sedation.

However, if it’s not properly implemented, you’re unlikely to see any significant results, and you can even end up doing more harm than good.

With that in mind, this article explores how things like patient harm, workload, time on the ventilator, and time in the ICU can all be increased when the ABCDEF Bundle is treated as nothing more than a checklist.

This is a real scenario involving a real patient whose name has been changed for anonymity, and for the purposes of this article, will be referred to as Diane.

How Ignoring the Risks of Immobility and Sedation Damaged Diane

Diane is a 54-year-old female with a history of methamphetamine abuse.

She lives with friends in a trailer park, works as a cannabis washer, and has a son that lives an hour away from her.

Diane arrived at the emergency department on the evening of June 17, 2024, with shortness of breath and hypoxia.

She asked to be intubated, and following intubation, Diane had an FiO2 of 90% and a PEEP of 10 before being admitted to the ICU for acute respiratory failure secondary to multifocal pneumonia, septic shock, and acute kidney injury.

Her toxicology screen was positive for amphetamines and THC.

Day One

Diane was intubated in the emergency department and sent to the ICU.

Ventilator Settings: A/C FiO2 90%, PEEP 10

IV Infusions: Propofol 40 mcg/kg/min, Fentanyl 75 mcg/hr, Norepinephrine 14 mcg/min, Vasopressin 0.03 units/min

Day Two

Ventilator Settings: A/C FiO2 50%, PEEP 8

IV Infusions: Propofol 30 mcg/kg/min, Fentanyl 50 mcg/hr, Norepinephrine 2 mcg/min, Vasopressin 0.03 units/min

PRN Total: Midazolam 6 mg

Documented RASS: -2

SAT, SBT, CAM, Early Mobility: None

Day Three

Ventilator Settings: A/C FiO2 40%, PS 5, PEEP 8

IV Infusions: Propofol 30 mcg/kg/min, Fentanyl 25-50 mcg/hr

Documented RASS: -1 to +1

SAT: Propofol was off for 1.5 hours and then resumed in response to the RASS of +1.

SBT: Failed

CAM and Early Mobility: None

Day Four

Ventilator Settings: A/C FiO2 50%, PEEP 8

IV Infusions: Propofol 35 mcg/kg/min, Fentanyl 50 mcg/hr

Documented RASS: -2

SAT, SBT, CAM, Early Mobility: None

Day Five

Wound care was consulted for a dark area on the buttocks.

Ventilator Settings: A/C FiO2 30%, PEEP 5

IV Infusions: Propofol 35 mcg/kg/min, Fentanyl 50 mcg/hr

PRN Total: Midazolam 4 mg

Documented RASS: -2 to +1

SAT, SBT, CAM, Early Mobility: None

Day Six

Ventilator Settings: A/C FiO2 40%, PEEP 5

IV Infusions: Propofol 35 mcg/kg/min, Fentanyl 50 mcg/hr

PRN Total: Midazolam 4 mg

Documented RASS: -2 to +1

SAT: Propofol was turned down and then off for 10 minutes, but Fentanyl stayed on.

SBT: Failed

CAM: First charted at 19

Early Mobility: None

Day Seven

Ventilator Settings: A/C FiO2 90%, PEEP 10

IV Infusions: Propofol 50 mcg/kg/min, Fentanyl 150 mcg/hr

PRN Totals: Midazolam 16 mg, Oxycodone 20 mg

Documented RASS: -2 to +2

SAT: Propofol turned down and then turned back up.

SBT: Failed

CAM: +

Early Mobility: None

Day Eight

Ventilator Settings: FiO2 85%-60%, PEEP 10-8,

IV Infusions: Propofol 50 mcg/kg/hr, Fentanyl 150 mcg/hr

PRN Totals: Midazolam 10 mg, Oxycodone 40 mg

Documented RASS: -3 to +3/4

SAT, SBT, Early Mobility: None

CAM: +

Day Nine

Ventilator Settings: FiO2 50%, PEEP 8

IV Infusions: Propofol 50 mcg/kg/min, Fentanyl 150 mcg/hr

PRN Totals: Midazolam 32 mg, Oxycodone 40 mg

Documented RASS: -2 to +2

SAT: Propofol was briefly decreased for SBT, and Fentanyl was continued.

SBT: Failed

CAM: +

Day 10

Propofol was turned off and Diane was extubated and fitted with a high-flow nasal cannula.

IV Infusions: Fentanyl 60 mcg/hr, Precedex 0.5 mcg/kg/hr

PRN Totals: Haldol 15 mg, Midazolam 17 mg, Oxycodone 20 mg

Documented RASS: 0 to +1

CAM: +

Early Mobility: None

Days 11-14

On day 11, After being fitted with a high-flow nasal cannula, Diane started to assist with being turned in her bed.

Then, on day 12, she was transferred to a chair with PT and discharged to the floor, and on day 13, she finally took her first steps in her room.

On day 14, Diane left the hospital against medical advice with a deep tissue injury and cognitive impairments, and required a walker even for very limited mobility.

Discussion

The team that provided the details of this case study admitted that this was a “normal” scenario in their unit.

Unfortunately, it’s not just this ICU, and the following gaps are very common in the culture and practices of many ICUs throughout the world.

That being said, this discussion is not to single out or belittle one specific ICU team, but rather to reveal problems I have observed throughout the critical care community, including:

Automatic Sedation

Was automatic sedation appropriate for Diane? And did she even have an indication for sedation?

Or was this just the conveyor belt approach of the ED and ICU?

Nurses’ notes reflect that Diane was distressed and asked to be intubated.

It is unclear if she was actively under the influence of methamphetamine at the time, but the notes seem to reflect that she was in distress from acute respiratory failure and not actively high on methamphetamines.

Nonetheless, if the ICU team that treated her had stopped sedation when she arrived at the ICU to evaluate whether it was necessary, it would have completely changed the course of her treatment.

Turning off sedation promptly while Diane still had the capacity to understand her surroundings and situation and communicate her needs to staff likely would have led her to be extubated on day two or three rather than on day 10.

This would have also prevented her complications, including ventilator-associated pneumonia, delirium, a stage 3 pressure injury, and ICU-acquired weakness.

RASS Scores

Diane’s sedation was ordered for a RASS score of -2 to 0, and while sedated, her RASS was documented at -2.

But while I was reviewing her chart, I noticed that the respiratory rates in her vital signs documentation were consistently the same as the respiratory rate set on the ventilator.

This leads me to suspect that she was likely sedated closer to a RASS of -4 or -5, which inhibits her from taking spontaneous breaths.

Although this was not the intention of the nurses who treated Diane, charting a RASS of -2 when the RASS is actually -4 or -5 is false documentation, which results in giving more sedation than should be prescribed, and is outside an RN’s scope of practice.

A RASS of -4 or -5 is also an independent predictor of mortality and an independent risk factor for delirium.

Ultimately, Diane likely did not have an indication for sedation but was still deeply sedated without further thought.

Delirium Screening

Delirium is a form of acute brain failure that doubles the risk of dying in the hospital and increases the risks of long-term brain injury by 120 times.

Luckily, we have the CAM-ICU, which is basically the “creatinine for the brain” as it allows us to assess and diagnose delirium.

Although Diane had significant risk factors for delirium, including a history of drug abuse, sepsis, septic shock, and hypoxia, for whatever reason, she was still deeply sedated and immobilized, which are both known risk factors for delirium.

Nonetheless, she was not screened for brain dysfunction until the end of her sixth day in the ICU.

This is the equivalent of not checking a patient’s creatinine levels for six days in the ICU.

In any case, not treating the brain with this same level of diligence led to a failure to prevent, assess, and treat acute brain failure.

Spontaneous Awakening Trials

Spontaneous awakening trials should occur as soon as there is no longer an indication for sedation, and the goal should be to discontinue sedation unless there is a real indication for it.

But Diane didn’t receive her first awakening trial until her third day in the ICU.

After 1.5 hours, sedation likely metabolized out of her system and her RASS increased to +1, but still, sedation was promptly resumed.

ICU Liberation guidance states that failed SAT criteria include agitation, but the term agitation is very subjective.

A RASS of +1 is restlessness, but is that a level of agitation that requires sedation?

Restlessness is a symptom of root causes like pain, anxiety, fear, confusion, delirium, desperation to communicate, etc., all of which is only masked by sedation, not treated.

And if Diane emerged from sedation with restlessness at a RASS of +1, she should have been given a means to communicate her needs so they could be addressed.

She should have also been mobilized to treat her anxiety, improve her comfort and adjustment to the ventilator, and especially to get her extubated.

Instead, she was resedated to a RASS of “-2” which in reality was more like a RASS of -4 or -5.

This pattern of quickly turning sedation off and turning it back on in response to movement was continued for seven days, which resulted in seven extra days on the ventilator, profound and prolonged delirium, a large deep tissue pressure injury, and ICU-acquired weakness.

And although SATs are performed by nurses, the responsibility for these outcomes is not solely on the nurses.

Respiratory therapists (RTs), physical therapists (PTs), occupational therapists (OTs), and physicians also carry this responsibility, and should have been asking questions like:

- “Why is she sedated?”

- “Why is she at a RASS of -4?”

- “And why aren’t we mobilizing her?”

The correct response in this situation should have been something like, “Her ventilator settings are minimal, so she should be strong enough to extubate. Let’s do the SAT and SBT together and get her extubated!”

Physicians especially needed to take the lead here, not least because they have the benefit of continuity of care and have the responsibility of critically thinking through the “big picture” and guiding their teams to see beyond that one shift or checklist.

For instance, when the physician was told in rounds that Diane failed the SAT and SBT, they should have probed further and asked:

- “Why did she fail?”

- “What criteria was unmet?”

- “Why was she at a RASS of +1?”

- “What did the RT see on the ventilator during the SBT?”

- “Why was that happening and what can we do to fix it so we can get her extubated?”

Ideally, during rounds on day three and beyond, a physician should have said, “OK team, she is probably ready to be extubated. At this point, she is only intubated because she’s sedated and sedated because she’s intubated. But she’s at high risk of delirium and ICU-acquired weakness, so let’s get sedation off, get her mobilized, and get her extubated.”

The physician should have also been available to support the team and follow up to ensure those orders were followed through with and Diane was successfully extubated.

What likely happened here is common among many ICU teams:

The RN tells the RT, “They failed their SAT,” so the RT can’t do an SBT, or the RT reports to the RN that they failed their SBT, and the RN then resumes sedation.

Then, during rounds, the RN reports to the physician and team that the patient “failed the SAT and SBT” and the physician says, “OK, we’ll try again tomorrow.”

Typically, in these situations, a physical or occupational therapist may be present, but instead of speaking up, often they’ll just stay quiet and think to themselves, “OK, I guess we’ll see her when she’s extubated.”

But what they should be saying is, “Can I go in with you to do a SAT? I can help get her up and then we can try another SBT. What time works for you guys?”

However, this is not usually what happens.

Spontaneous Breathing Trials

By Diane’s third day in the ICU, her ventilator settings were fairly low, and she had met the criteria for trying a spontaneous breathing trial.

My suspicion is that if she had been awake, mobile, taking spontaneous breaths, and coughing, she would have been able to be mobile and clear her secretions from pneumonia more effectively, and therefore may have had an even lower PEEP by that time.

I was not present during this patient’s breathing trial, but speculations can be made as to why Diane “failed” her breathing trials, including:

Delirium: Diane was at high risk of delirium, and this can result in her becoming tachypneic and dyssynchronous with the ventilator.

Anxiety: Diane likely had poor coping mechanisms at baseline and emerging from sedation to realize you’re intubated and strapped to a bed with strangers looming over you would be anxiety-provoking for anyone. This can result in rapid and even shallow breathing.

Pain: Diane could have been in pain, as well, which could also have led her to have rapid or shallow breathing.

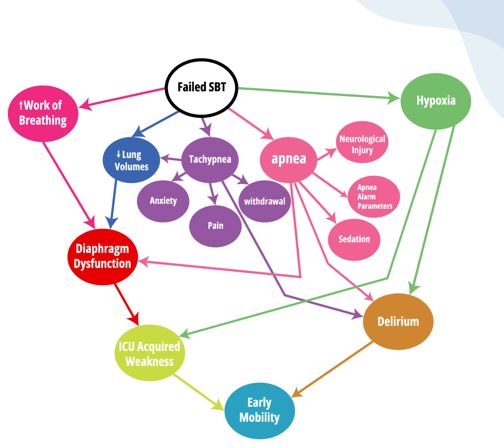

The image below shows the main causes of failed spontaneous breathing trials and the underlying causes of these failures, most of which are rooted in delirium and ICU-acquired weakness and can be treated using mobility.

All things considered, if this ICU team had the knowledge, perspective, and culture to critically think through Diane’s SBT, she would have been awake and mobile on day one.

The team would have been focused on a successful SBT shortly after intubation, rather than waiting until ventilator settings are minimal to finally think about how to get her off the ventilator.

And they would know that by keeping her awake and mobile they could prevent delirium and ICU-acquired weakness, expedite the improvement of her pneumonia, and keep her brain and muscles intact so she could independently breathe much sooner.

This way, by the time she was ready for an SBT, she wouldn’t need a SAT. She would already be awake, calm, and strong, and the SBT process would be simple and successful.

Instead, Diane’s SBTs were approached in a robotic way, with RTs simply checking the SBT box on their task list.

The RT changed the ventilator to spontaneous mode when the nurse stopped the Propofol, and likely looked at numbers like her respiratory rate and noted that they met failure criteria.

They then documented the SBT as failed, the RN resumed sedation, and the RT resumed a controlled mode on the ventilator.

Everything was documented, and it looked compliant on the ABCDEF Bundle dashboard, but was this actually the best approach for Diane?

In any case, empowering RTs to critically think through SBTs could have drastically changed this patient’s outcomes, and the workload and health care costs for the hospital where she was treated.

Mobility

In the ICU, the timing of mobility is imperative.

To prevent post-ICU syndrome, patients must be mobilized within 72 hours after ICU admission.

If patients are mobilized within 48 hours after intubation, this can improve their return to baseline functional status by 24% and improve cognitive function by 20% one year after discharge.

Mobility is also one of the only tools we have to prevent and treat delirium and keep the respiratory muscles intact so patients can independently breathe once the acute indication for mechanical ventilation is resolved.

The only exclusion criteria for mobility Diane met was that she was deeply sedated, although she should have been awake and mobile on day one.

The ICU team that treated her should have been anticipating that she’d be awake and walking on the ventilator to treat her pneumonia, prevent delirium and ICU-acquired weakness, and get her ready to be extubated and discharged home as soon as possible.

Instead, Diane didn’t get out of bed until day 12.

This could be charted as “bed rest” on the ABCDEF Bundle dashboard, which creates the appearance of compliance for screening.

But ultimately, the failure to promptly mobilize Diane was a failure to truly practice the ABCDEF Bundle.

The Price Paid

Health Care Costs

On average, one day in the ICU costs $5,521, and ventilator costs alone are $2,401 per day.

By my estimates, Diane probably could have been extubated on day two if she had been awake and walking and should have been extubated on day three at the latest.

At any rate, failing to truly practice the ABCDEF Bundle cost this ICU about $16,807 in ventilator costs alone.

Had Diane been extubated on day three, she likely would have been on a nasal cannula and sent to the floor. But instead, she stayed in the ICU until day 12, and those nine extra days in the ICU cost around $49,689.

On day seven, Diane developed ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), which on average costs $58,520.

She also ended up with a stage 3 hospital-acquired pressure injury (HAPI) which costs $8,371, but Diane would not have developed any of these complications if she had been made to be promptly awake and mobile.

Diane didn’t sue the hospital, but lawsuits for these kinds of pressure injuries cost hospitals about $200,000 on average.

And Diane may have saved this hospital some money by leaving early against medical advice.

Yet she left with severe cognitive impairments, weakness, and an untreated deep tissue pressure injury.

At this point, she is at high risk of readmission due to complications like infection in the pressure injury, pneumonia, falls, and more.

But if she’d been awake and mobile, Diane would have been much more likely to safely return to her home sooner and stay there.

Workload and Staffing

It’s likely that Diane was perceived as an “easy patient” since she was sedated and immobilized for most of her stay in the ICU.

But what many clinicians don’t realize is that failing to practice the ABCDEF Bundle in the way it was meant to be applied can drastically increase their workload.

For the seven extra days that Diane spent on the ventilator, here’s all the extra work ICU clinicians had to do:

Respiratory Department

- Ventilator checks and charting every 4 hours: 42 extra times

- Oral care every 4 hours: 42 extra times

- Suctioning every 4 hours with ventilator checks: 42 extra times

- More care sessions with ventilator checks, charting, suctioning, etc.

- Spontaneous breathing trials: 5 extra times

- Breathing treatments every 4-6 hours: 28-42 extra times

- Setting up a high-flow nasal cannula after extubation

Registered Nurses

- Oral care every 4 hours: 42 extra times

- Turns every two hours: 84 extra times

- Hourly documentation of vital signs: 168 extra times

- Restraint assessment and documentation every 2 hours: 84 extra times

- PRN suctioning about 10 times per 24 hours: 70 extra times

- Daily bed bath: 7 extra times

- PRN repositioning/boosting about six times per 24 hours: 42 extra times

- Full assessment and documentation every 12 hours: 14 extra times

- 2-3.6 100 ml Propofol bottle changes per day: 18 extra times

- 1.2-3.6 changes of 100 ml Fentanyl bags per day: 14.8 extra times

- RASS every two hours: 84 extra times

- Double-checking controlled substances

- Restraint check and charting every two hours: 84 extra times

- SAT: 4 extra times

Physicians

- Recording daily medical notes: 7 extra times

- 70 extra minutes spent discussing in rounds

- 7 additional exams

Post-ICU Life

Diane has significant risk factors for post-ICU syndrome.

For every one day of delirium, for instance, there is a 35% increased risk of long-term cognitive impairments on the same level as mild Alzheimer’s and moderate traumatic brain injury.

It’s impossible to know exactly when Diane’s delirium started or ended, since she was not screened for delirium until day six, and not screened for it on the floor when she left against medical advice.

But she likely started to have delirium around day two after intubation.

The occupational therapy notes from her last day in the hospital indicate that she had persistent severe cognitive impairments, so at this point, she was either still damaged from delirium or still actively in delirium.

In any case, she likely suffered from delirium for at least six days, but it could have been up to 12 days or more.

Even at baseline, she probably had cognitive impairments due to her methamphetamine use, not to mention the fact that she was malnourished and lived with multiple friends in a trailer.

With this new trauma, cognitive impairments, mobility deficits, and large deep tissue pressure injury, will she be able to survive and thrive after leaving the hospital?

The rest of Diane’s story is unknown to me, yet I feel confident in assuming that post-ICU syndrome will play a significant role in the trajectory of her life.

Final Words

Diane’s trip to the hospital should have amounted to nothing more than a simple case of pneumonia that resulted in her walking out of the ICU no more than three days after admission.

Instead, she spent a total of 12 days in the ICU, deeply sedated and immobile for most of it, and as a result, she suffered unnecessarily.

If any member of this ICU team had spoken up and drawn attention to the risks of immobility and sedation, and the real focus of the ABCDEF Bundle, which is to keep patients awake, communicative, autonomous, and mobile, Diane would have been extubated on day two or three instead of day 10, and much of her suffering would have been avoided.

With that in mind, can we stop seeing this kind of inhumane and senseless treatment as normal?

Can we see our patients as humans and consider their lives as a whole?

Can we critically think through our interventions and use sedation as a high-risk tool only to be implemented when unavoidable?

And can we understand and practice early mobility as a life-saving treatment in the ICU?

I have great faith that humanizing the ICU and practicing safely and efficiently is within our reach.

If you and your team are ready to master the ABCDEF Bundle and create an Awake and Walking ICU, please don’t hesitate to sign up for a free consultation.