As far as the early mobility community is concerned, the benefits of early mobility in the intensive care unit are not up for debate.

There are mountains of evidence to show these benefits and support the safety and efficacy of early mobility in the ICU, and this is something I’ve documented repeatedly.

But unfortunately, ICUs that adhere to these kinds of evidence-based practices are still in the minority today.

At the same time, ICU culture tends to discourage any form of change, and prefers to employ more conventional forms of care.

As a result, despite the fact that evidence-based sedation and mobility protocols have been shown to save and preserve lives, I still have clinicians telling me that these practices are unsafe and ineffective.

So, when a recent study was published questioning the efficacy and safety of these practices, swathes of skeptics took to Twitter to tweet the study’s conclusion, which claims more mobility did not benefit patient outcomes. Tweets were widely shared using this study to support claims that “rest is best.”

But it seems like very few people went beyond the study’s abstract, and even fewer took the time to analyze its methodology.

If they had, many of them would have realized that this research is missing quite a bit of context, and may not have proved what they think it does.

In any case, this study has the early mobility community in an uproar, so I figured I should break it down a bit, analyze its methodology, and provide some proper context, so you can have a better understanding of how it came to its conclusions and what it really means.

I was also lucky enough to be able to interview the main author of this study, so if you want to learn more about it, you can check out Episode 117 of my Walking Home From The ICU podcast.

What Was the Conclusion of This Study on Early Mobility in the ICU?

The study in question here is called Early Active Mobilization during Mechanical Ventilation in the ICU, and it was published in November of last year.

Believe it or not, the conclusion of this study states that “an increase in early active mobilization did not result in a significantly greater number of days that patients were alive and out of the hospital than did the usual level of mobilization in the ICU.”

Simultaneously, it also states that early mobility in the ICU “was associated with increased adverse events.”

In other words, when the study looked at the number of days that the patients in this study were alive and out of the hospital, there was no significant difference between the patients who had more early mobility and those who received “standard care.”

Also, the patients who received more early mobility were more likely to experience events that had the potential to have an adverse effect on their health and safety.

Now, if you know anything about early mobility, this probably sounds absurd, but regardless of what you think about these practices, it’s important to understand how this study came to its conclusions.

How Did This Study on Early Mobility in the ICU Come to These Conclusions?

Several factors led the authors of this study to come to such controversial conclusions, but in order to understand how that happened, we have to look at each and every one of them.

Nearly all of these aspects relate to the study’s methodology, which has raised concerns in the ICU liberation world.

Below I’ve laid out all the factors that need to be considered if you want to understand how this study came to these conclusions.

Lack of Consistency

One of the most glaring issues with this study is that it compares data from 49 hospitals and six different countries.

One of the most glaring issues with this study is that it compares data from 49 hospitals and six different countries.

Why is that a problem?

Clearly there is benefit in taking data from many different locations, as studies with larger sample sizes and more diverse populations tend to have more reliable results. Yet, the lack of consistent care across the centers in this study is certainly cause for concern.

With so many different ICUs, in so many different countries, each with varying ICU cultures, standards of care, and levels of education, it’s pretty much impossible to control the quality of care that the patients in this study were receiving.

And in a study like this, it is vital to have control over the quality of care, and reliability in things like the level of sedation or kinds of mobility sessions patients receive. Inconsistencies in care must be taken into consideration when evaluating the impact of the intervention.

Certainly, instruction can be provided to clinicians involved in the study to operate in a specific way, and when I interviewed the study’s author on my podcast, she insisted that the study was as controlled as it possibly could be. Yet, with data coming from so many different sources, it’s just not feasible to ensure everyone is practicing and documenting interventions in a uniform manner.

A perfect example of this, as it pertains to this study, is the use of Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) scores to determine levels of sedation.

In order to calculate a RASS score, a clinician will have to answer a series of questions about the patient’s condition, which are innately subjective, meaning they may or may not offer an accurate description of a patient’s level of sedation.

Moreover, if the clinician isn’t educated on how RASS works, or is inconsistent in their assessments, then these scores can be easily misinterpreted.

From my perspective, using data that risks inconsistency is like comparing apples to oranges, which means it’s not particularly meaningful and doesn’t lend itself to the accuracy of the study’s conclusions.

Lack of Contrast

Unfortunately, this study also suffers from a lack of contrast.

What do I mean by that?

Well, the first thing to point out is that this study looked at two groups of patients.

One group received whatever early mobility protocols were standard practice in the ICU where they were admitted, and the other group received about 12 additional minutes of early mobility.

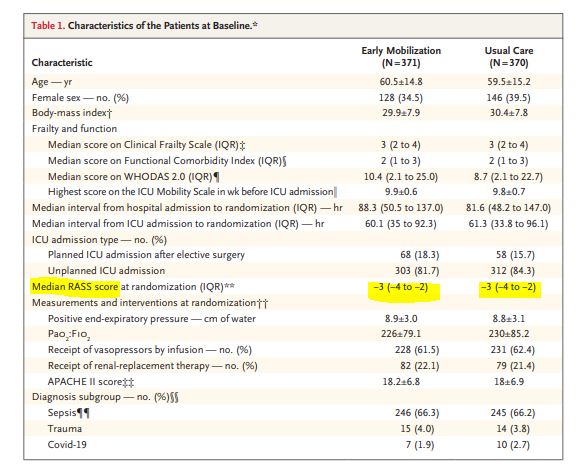

At the time the study was conducted, these patients had already been sedated for a period of time, and as you can see from the table below, the median RASS score for both groups in the study was -3, which indicates moderate sedation and is the third highest level of sedation on the scale.

To put things in perspective, if a patient has a RASS of -3, that means that they exhibit some form of movement when spoken to, but they can’t even make eye contact.

In other words, if you’re this sedated, you’re going to be pretty out of it, and it’s not likely that you’d be able to reach a significant level of mobility.

The median timing of randomization was two and a half days, meaning that when patients were mobilized around day three of the study, it was likely their fifth or sixth day after admission. Moreover, most of these patients had probably been sedated and immobilized for the initial five days.

That being said, how likely is it that 12 more minutes of mobility would actually have a significant impact after five days of profound atrophy and delirium?

Now, to be fair, what the ICUs in this study were doing in terms of early mobility is actually much better than what’s done in a lot of ICUs, many of which don’t even have early mobility protocols.

But if you take this group of patients, which is already receiving care that’s well above average, and try to compare them to another group that’s receiving essentially the same level of care, with only 12 minutes more early mobility, that lack of contrast means you’re not likely to see much of a difference between the two groups.

However, if you were to take a group of patients that were receiving some of the worst forms of conventional ICU care, like being deeply sedated for weeks, and compare them to patients who received evidence-based care, meaning they were never sedated and were up and walking right away, then you would see a pretty big difference, and the benefits of early mobility would likely be obvious.

But this study didn’t do that.

Instead, it chose to compare two relatively homogenous groups of patients, so it’s no surprise that there wasn’t much of a difference between the outcomes of the two groups, and this definitely says more about the study’s methodology than it does about early mobility.

When I spoke with her on my podcast, the study’s author felt that there was enough of a difference between the two groups to make a meaningful comparison and see a change in outcomes. But she also admitted that they weren’t really measuring levels of sedation, aside from the RASS score.

This is a significant concern for me in terms of the study’s lack of contrast, and questionable methodology, because you can’t legitimately measure mobility without considering sedation, as they’re so intimately connected.

With that said, as far as I’m concerned, there should have been more of a contrast between the two groups in this study because if most patients were deeply sedated and immobilized for the first few days and then remained sedated with breaks for mobility, how could you really see a significant difference in terms of their levels of mobility?

Lack of Context

Somewhat unrelated to this study’s methodology, but something else that concerned me, nonetheless, was the lack of context in the study.

For example, the study states that “Adverse events…were reported in 34 of 371 patients (9.2%) in the early-mobilization group and in 15 of 370 patients (4.1%) in the usual-care group”.

The study classified adverse events as things like cardiac arrhythmias, hypoxia, hypotension, fainting, falls, unplanned extubation, etc., but most of the events were cardiac arrhythmias.

Now, the group of patients who received more early mobility did suffer more than double the number of adverse events, when compared to the usual-care group, but this outcome is still very minor.

This study looked at 750 patients, and less than 50 of them had any sort of adverse event, so while there were twice as many adverse events that occurred within the early-mobilization group, these numbers are still incredibly low.

At the same time, there is compelling evidence to show how rare these adverse events actually are, and none of this is referenced in the study.

For example, there is a meta-analysis that looked at more than 7,500 patients, and tens of thousands of mobility sessions, which found that “early mobilization and rehabilitation in the ICU appears safe, with an overall cumulative incidence of potential safety events of 2.6% and rare (0.6%) medical consequences”.

In other words, the incidence of adverse events from early mobility is extremely low, and the chance of serious adverse events happening due to early mobility is likely less than one percent.

This lack of context feeds into the cultural-based fear clinicians have of these practices, and further obscures the real issues at stake here.

It does not take into consideration the fact that the risks shown in this study were relatively minor, especially when compared to the serious risks posed by leaving patients sedated and immobile for weeks at a time, which is still standard practice in many ICUs today.

Differing Definitions

Another concern with this study is the fact that the terms early and mobility can mean vastly different things to different clinicians, which also contributes to the study’s lack of consistency.

For example, to one clinician, the term early could mean that the patient is in some way mobile within the first 24 hours after admission, whereas another clinician might think it means that they’re mobile at any time during their stay in the ICU, which could be three weeks after admission, or three days.

On the other hand, there could also be a considerable amount of confusion over the term mobility.

To some clinicians, this term could simply mean passive range of motion, which refers to moving the patient’s limbs around when they’re under sedation and/or comatose. But another clinician might think mobility means getting the patient off of sedation so they can get out of bed, walk around, or climb stairs.

Clearly, these practices are not the same, despite both being classified as forms of mobility.

That being said, one of the reasons why these kinds of studies can have such variable outcomes, and end up coming to opposite conclusions is that not everyone defines early mobility in the same way.

For example, this study specifically allowed being upright in a tilt table to qualify as “standing.”

Such definitions should play a significant role in what information we glean or what conclusions we draw from the study.

Mountains of Evidence

Before I wrap things up here, I think it’s important to provide some evidence backing up the safety and efficacy of early mobility in the ICU.

Over the years, there have been countless studies on this subject showing the benefits of using these kinds of evidence-based practices.

Below, I’ve included links to several of these studies so you can review the evidence for yourself.

- A study on early mobilization within the first few days of admission to the ICU found that this practice can decrease length of stay and mortality while improving outcomes, functionality, and self-care at discharge, and can also decrease readmissions, increase strength and independence, and reduce costs in the ICU.

- A study on early mobility during the early stages of critical illness found that this practice can decrease the duration of patients’ delirium, allow them to have more ventilator-free days, and create better functional outcomes at hospital discharge.

- A study on goal-directed mobilization in the ICU found that this form of mobilization can shorten patients’ length of stay, and improve their functional mobility at hospital discharge.

- A study on the association between early mobility and pneumonia found that early mobility can decrease the risk of hospital and ventilator-associated pneumonia by 40 percent or more.

- A study on non-pharmacological delirium prevention found that early mobility can reduce the incidence of delirium.

If you’d like more information, you can also check out this library of links to studies on early mobility.

Do you want to implement evidence-based practices, like early mobility, in your ICU? We can walk you through the entire process, so please don’t hesitate to contact us.