Health care inequality in critical care medicine is multifactorial and negatively impacts patient outcomes [18].

During COVID-19, for instance, it was noted that Hispanic patients were more at risk of having severe COVID-19 infections, and despite their younger age, they had a higher mortality rate.

Socioeconomic disparities, lack of access to health care, timing, and quality of care all play a part in the contrast in outcomes for Hispanic patients in the ICU [14], and outdated sedation practices in the ICU are causing greater inequality in and after the ICU for Hispanic patients.

Fortunately, the ABCDEF Bundle has the power to decrease seven-day mortality by 68% [12], but compliance with the ABCDEF Bundle tends to be lower when it comes to the care Hispanic patients receive.

And although delirium doubles the risk of dying in the hospital, [15], Hispanic patients have half the odds of having delirium assessments performed when compared to non-Hispanic patients [5].

What’s more, benzodiazepines are known to increase ventilator-associated pneumonia, time on the ventilator and in the hospital, and they can also increase delirium [19] and mortality by about 20% [7]. However, during COVID-19, Hispanics were more likely to receive benzodiazepines than non-Hispanic patients [20].

But the health care inequality that we see in sedation practices is not unique to COVID-19.

A secondary analysis of data from the ROSE study [9], which evaluated the care of patients with ARDS during 2016-2018 revealed shocking revelations.

For example, despite deep sedation being an independent predictor of death [17], Hispanic patients were 5 times more likely to be deeply sedated than non-Hispanic patients [2], and the failure to practice the ABCDEF Bundle may be a significant contributing factor to the 44% increased mortality rate among Hispanic COVID-19 patients when compared to non-Hispanic White patients [14].

Sedation practices in the ICU can also exacerbate socioeconomic and health care inequality long after the ICU, not least because deep sedation is independently associated with delirium [13].

Delirium increases the risks of long-term cognitive impairments by 120 times [6] and increases the rate and severity of post-ICU PTSD [16]. These post-ICU cognitive and psychological impairments can have devastating impacts on employment and quality of life after a patient leaves the ICU.

The reality is 49% of patients who have suffered from ICU delirium are still newly unemployed 12 months after discharge [11].

What’s more, access to cognitive, physical, and psychological rehabilitation after the ICU may be limited for Hispanic ICU survivors, and financial support may be limited if they become disabled.

What’s Causing This Health Care Inequality for Hispanic Patients?

In Episode 115 of my Walking Home From The ICU podcast [4], Dr. Thomas Valley discusses the findings of his study that revealed the lethal disparities in sedation practices among Hispanic patients even before COVID-19 [2].

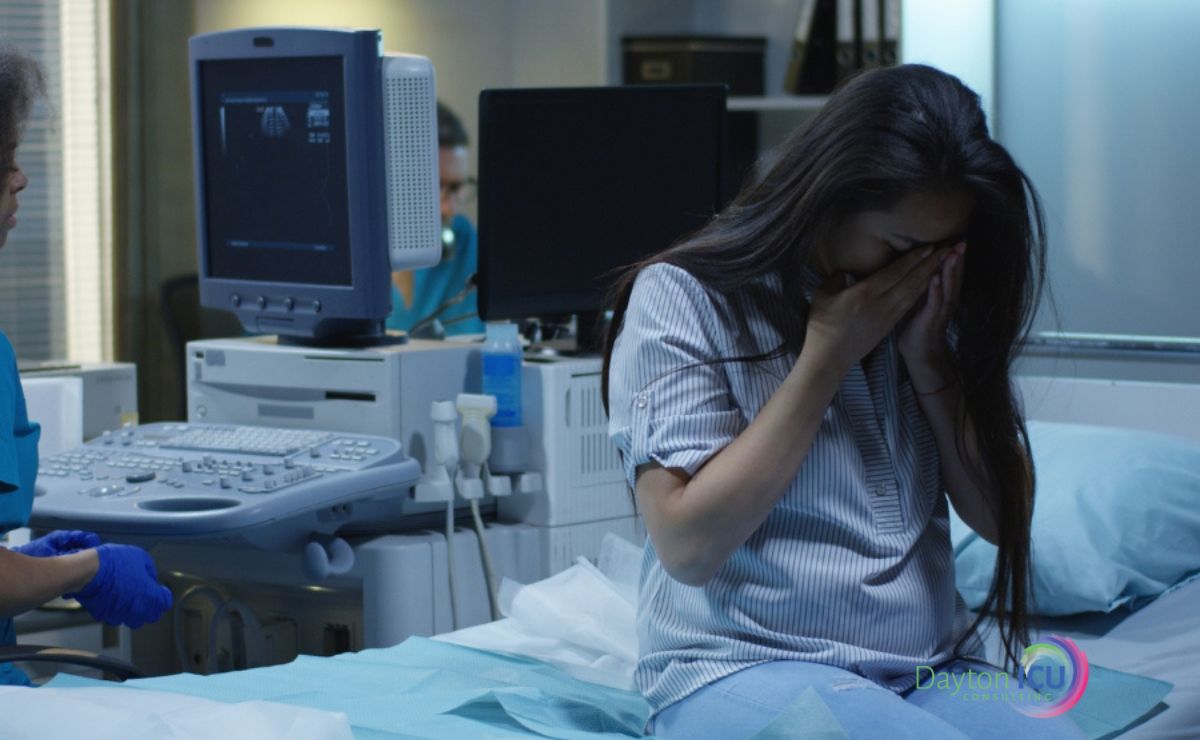

He speculated that a language barrier may lead to higher levels of sedation and the inability to screen for delirium, as many Hispanic patients may not speak English and do not have a way to understand and communicate with their health care providers.

This inability to report pain, needs, wants, and concerns, and to have questions addressed, can escalate anxiety and agitation, influencing clinicians to continue and even increase sedation.

Nurses have reported that their primary method of non-verbal communication in the ICU with intubated patients is reading patients’ lips, thumbs up or down, and head nodding [1], mainly because their health system fails to provide evidence-based resources or education on best practices and despite four decades of research reporting these methods are wrought with error and are ineffective [21].

Inadequate for most patients, these methods are simply not feasible options for patients who do not understand or speak English, and the inability to communicate when critically ill can have deadly repercussions.

It’s been shown, for instance, that problems with communication in the ICU can cause a threefold increased risk of having an adverse event and can also make patients 26% more likely to suffer multiple adverse events [3].

Communication is a basic human right [8], and the lack of ICU communication solutions for all patients, regardless of race, language, and ability to verbalize is a human rights violation that exacerbates racial disparities in health care and worsens outcomes in the ICU.

To not pursue all means to establish effective communication for these patients is no less neglectful than to leave a patient febrile or hypotensive.

That being said, while there may have been a rationale for ineffective ICU communication to be the expected norm for intubated patients three or four decades ago, we now know how to address this issue, and not addressing it with an evidence-based approach, like the one provided by the ABCDEF Bundle, is nothing short of neglect.

The ABCDEF Bundle is the roadmap to saving and preserving lives for all patients, regardless of race, during and after the ICU.

The goal of this approach is “to produce patients who are more awake, cognitively engaged, and physically active” [12] and to “facilitate patient autonomy and the ability to express unmet physical, emotional, and spiritual needs.”

It is impossible to fully optimize and apply the ABCDEF Bundle if access to communication is not available for each patient in their own language.

Bridging the ICU communication gap will help bring better equity to care and outcomes for Hispanic patients. And if you want to reduce sedation exposure, start by reducing the need for it by ensuring intubated patients are communicating effectively.

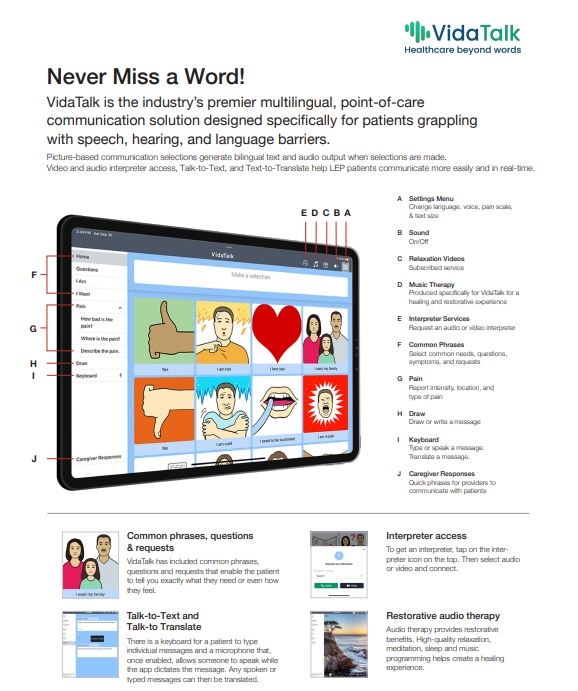

VidaTalk Offers a Solution

For many patients, having access to communication with health care providers can be the difference between life and death.

Being able to effectively communicate allows them to understand their situation, be informed and empowered to make decisions for their care, and have pain and anxiety adequately treated.

At the same time, it also enables them to be awake and mobile while intubated, which can drastically improve their opportunity to survive and thrive both during and after the ICU.

With that in mind, I am ecstatic to share a solution to this problem in the form of a software tool called VidaTalk.

VidaTalk is the only tool that provides non-verbal communication for intubated patients in over 40 different languages [10].

If your team is interested in providing more equitable, ethical, and humane practices in your ICU, Dayton ICU Consulting and VidaTalk are ready to help.

For a free demo of VidaTalk and consultation with Dayton ICU Consulting, email info@daytonicuconsulting.com or schedule a free consultation today.

References:

- Al-Yahyai, R., Arulappan, R., & Matua, G.A., et al. (2021). Communicating to Non-Speaking Critically Ill Patients: Augmentative and Alternative Communication Technique as an Essential Strategy. SAGE Open Nursing, 7.

- Armstrong-Hough, M., Lin, P., Venkatesh, S., Ghous, M., Hough, C. L., Cook, S. H., Iwashyna, T. J., & Valley, T. S. (2024). Ethnic Disparities in Deep Sedation of Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in the United States: Secondary Analysis of a Multicenter Randomized Trial. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, Advance online publication.

- Bartlett, G., Blais, R., Tamblyn, R., Clermont, R. J., & MacGibbon, B. (2008). Impact of patient communication problems on the risk of preventable adverse events in acute care settings. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 178(12), 1555–1562.

- Dayton, K. (2022). Episode 115: Sedation By Race. Walking Home From The ICU.

- DeMellow, J. M., Kim, T. Y., Romano, P. S., Drake, C., & Balas, M. C. (2020). Factors associated with ABCDE bundle adherence in critically ill adults requiring mechanical ventilation: An observational design. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 60, 102873.

- Dziegielewski, C., et al. (2021). Delirium and associated length of stay and costs in critically ill patients. Critical Care Research and Practice.

- Lee, H., Choi, S., Jang, E. J., Lee, J., Kim, D., Yoo, S., Oh, S. Y., & Ryu, H. G. (2021). Effect of Sedatives on In-hospital and Long-term Mortality of Critically Ill Patients Requiring Extended Mechanical Ventilation for ≥ 48 Hours. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 36(34), e221.

- Mcleod, S. (2018). Communication rights: Fundamental human rights for all. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(1), 3–11.

- The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute PETAL Clinical Trials Network. (2019). Early Neuromuscular Blockade in the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine, 380(21), 1997–2008.

- News – Vidatak. https://vidatak.com/ (n.d.)

- Norman, B. C., Jackson, J. C., Graves, J. A., Girard, T. D., Pandharipande, P. P., Brummel, N. E., Wang, L., Thompson, J. L., Chandrasekhar, R., & Ely, E. W. (2016). Employment Outcomes After Critical Illness: An Analysis of the Bringing to Light the Risk Factors and Incidence of Neuropsychological Dysfunction in ICU Survivors Cohort. Critical Care Medicine, 44(11), 2003–2009.

- Ely, E. W., et al. (2019). Caring for Critically Ill Patients with the ABCDEF Bundle: Results of the ICU Liberation Collaborative in Over 15,000 Adults. Critical Care Medicine, 47(1), 3–14.

- Rasulo, F. A., Badenes, R., Longhitano, Y., Racca, F., Zanza, C., Marchesi, M., Piva, S., Beretta, S., Nocivelli, G. P., Matta, B., Cunningham, D., Cattaneo, S., Savioli, G., Franceschi, F., Robba, C., & Latronico, N. (2022). Excessive Sedation as a Risk Factor for Delirium: A Comparison between Two Cohorts of ARDS Critically Ill Patients with and without COVID-19. Life, 12(12), 2031.

- Ricardo, A. C., Chen, J., Toth-Manikowski, S. M., Meza, N., Joo, M., Gupta, S., et al. (2022). Hispanic ethnicity and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19. PLoS ONE, 17(5), e0268022.

- Salluh, J., et al. (2015). Outcome of delirium in critically ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal, 350.

- Schelling, G., Stoll, C., Haller, M., Briegel, J., Manert, W., Hummel, T., Lenhart, A., Heyduck, M., Polasek, J., Meier, M., Preuss, U., Bullinger, M., Schüffel, W., & Peter, K. (1998). Health-related quality of life and posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Critical Care Medicine, 26(4), 651–659.

- Shehabi, Y., Bellomo, R., Reade, M. C., Bailey, M., Bass, F., Howe, B., McArthur, C., Seppelt, I. M., Webb, S., Weisbrodt, L., Sedation Practice in Intensive Care Evaluation (SPICE) Study Investigators, & ANZICS Clinical Trials Group (2012). Early Intensive Care Sedation Predicts Long-Term Mortality in Ventilated Critically Ill Patients. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 186(8), 724–731.

- Soto, G. J., Martin, G. S., & Gong, M. N. (2013). Healthcare Disparities in Critical Illness. Critical Care Medicine, 41(12), 2784–2793.

- Spiegler, P. (2014). Benzodiazepines in the ICU: Enough Is Enough!. Clinical Pulmonary Medicine, 21(6), 288–289.

- Valley, T. S., Iwashyna, T. J., Cook, S., Hough, C. L., & Armstrong-Hough, M. (2021). Associations Among Patient Race, Sedation Practices, and Mortality in a Large Multi-Center Registry of COVID-19 Patients. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 203(9).

- Happ, M. B. (2021). Giving Voice: Nurse-Patient Communication in the Intensive Care Unit. American Journal of Critical Care, 30(4), 256–265.