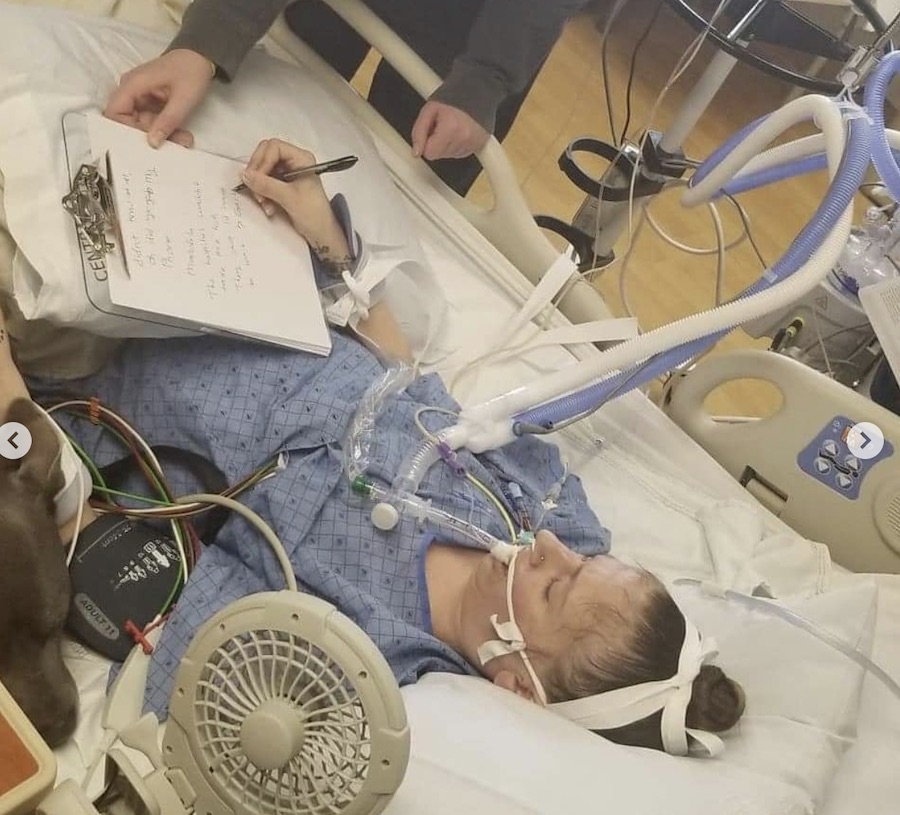

Nurses enter critical care medicine to alleviate human suffering, support patients in their most vulnerable moments, be patient advocates, do no harm, and save lives.

But being a critical care nurse is physically, emotionally, and mentally challenging.

Many factors have resulted in the loss of thousands of expert nurses, creating the staffing crisis we’re currently facing.

Poor support for nurses, lack of career fulfillment, moral injury [18], high emotional exhaustion, and low personal accomplishment [33] all contribute to RN burnout.

Moreover, the current practice of automatic sedation and immobility for every intubated patient has exacerbated the challenge of keeping ICU nurses at the bedside, ultimately increasing RN burnout through increased workload, less team support, and poor patient outcomes.

Other side effects of these outdated practices, such as high rates of delirium and ICU-acquired weakness, are also worsening the nursing crisis.

But now that we have the ABCDEF Bundle, there is no reason for things to continue this way.

The ABCDEF Bundle [35] is a readily available toolkit to help guide clinicians on how to use evidence-based sedation and mobility practices.

Failing to put these practices in place deprives nurses of accomplishing their mission and having the satisfaction of watching their patients have the best outcomes, and I’ve experienced this firsthand.

I started my nursing career in an Awake and Walking ICU, where nearly all patients were awake after intubation and doing their highest level of mobility shortly thereafter.

But after a few years, I started working as a travel nurse and was shocked to find that this was not standard practice throughout the nine other ICUs I worked in.

I was losing my love of nursing and briefly considered leaving the field.

When I returned to the Awake and Walking ICU, I realized that my job was far more fulfilling and manageable because of the changes in the use of sedation and increased mobility afforded by the protocols outlined in the ABCDEF Bundle.

These evidence-based practices helped preserve my patients’ mental and physical capabilities, which reduced their delirium, decreased their length of stay, and increased their participation in their care.

Keep reading if you want to learn more about how these protocols can help to mitigate RN burnout.

But before I continue, I want to give a special thank you to all the ICU nurses who contributed to this article, including Roni Kelsey, Jessica Williams, Liz McQueen, Richard Woods, Tara Arroyo, James Fletcher, Allison Diburro, Tara Dagesse, Sarah Vance, Sean Karbach, Annie, and those who chose to be anonymous.

Delirium and RN Burnout

Delirium is a life-threatening brain dysfunction that increases the psychological burden, risks, liabilities, and staffing demands on nurses [36].

Nurses report high emotional stress, strain [23], and burden [25] when caring for patients with delirium.

Protecting and monitoring patients who are confused, scared, combative, and impulsive during hyperactive delirium is a significant challenge for nurses, and the responsibility to keep patients safe with their lines and tubes intact can be a heavy burden.

Yet they are forced to work in an environment that leaves both patients and nurses vulnerable to the complications of delirium.

Delirium is at the root of many adverse events in the ICU.

For instance, delirium increases the risks of unplanned extubation by 11.6 times [24] and increases the risk of all line and tube removals [42].

The sooner my ICU patients are sedation-free, honestly, the easier my job is to care for them. Even intubated, they are better about caring for themselves, communicating their needs, and they end up protecting their ET tube.

− Richard Woods, Utah

Over 50% of falls in the ICU occur in the setting of delirium, delirium increases the risk of falls by 3.85 times [26], and previous sedation and analgesia infusions increase the risk of falls by 60% [45].

Deep sedation is also an independent predictor of mortality and delirium, as it doubles the risk of dying in the hospital [34], and for every one day of delirium there is a 10% increased risk of death [15].

What’s more, delirium not only increases harm to patients, but also increases the amount of violence nurses [21] have to endure, causing them to fear for their safety and suffer from diminished self-esteem and inner conflicts.

Delirium also increases time in the ICU on average by 4.47 days and 6.67 in the hospital [12], doubles the nursing hours required for care [38], contributes to difficulty interpreting patients’ needs, and can increase nurse discomfort [39].

Caring for delirious patients also contributes to nurse burden [2], and delirium severity is actually a predictor of nurse distress [4].

Caring for another human that you just met takes a special kind of energy. But to care for a confused and combative stranger that you are also tasked with keeping safe is even more stressful and requires even more time and energy.

− Roni Kelsey, Washington

Hypoactive delirium can be “safer” and “easier” to manage, but patients depend on nurses for turning, toileting, bathing, and nutrition.

In any case, when patients suffer from delirium, nurses lose the opportunity to have calm, compliant, awake, and engaged patients. They are deprived of connection and communication with those they work diligently to serve.

I honestly think losing that connection with patients during COVID was the hardest part for me. I lost a huge portion of the most satisfying part of my job and it hurt.

− Tara Arroyo, Salt Lake City, Utah

When patients are sedated for prolonged periods of time, the burden falls on their nurses, who must do the awakening trial to unmask the delirium and agitation the patient is suffering from under sedation.

Nurses are held liable for unplanned extubations and yet they are often left alone with confused, scared, and hyperactive patients. This increases risks for nurses and patients and can contribute to RN stress and exhaustion.

Moreover, nurses are challenged and expected to perform all elements of care from medication passes to activities of daily living, all while patients are unable to participate in their care or voice concerns when heavily sedated and faced with an increased risk of having poor outcomes.

Watching patients suffer and then die despite great effort and care comes at a high price for nurses.

I extubated a patient and transferred them to the floor. I lost it and started crying. I realized at that moment that it had been so long since I had extubated a patient and they got better.

− Liz McQueen, Colorado [7]

ICU-Acquired Weakness and RN Burnout

ICU-acquired weakness is the devastating loss of muscle mass and function that occurs in 50% of patients in the ICU [5]. It results in significant limb weakness and is associated with diaphragm atrophy and dysfunction.

This dangerous and burdensome condition rapidly develops as patients can lose 40% of lean muscle mass within one week of bedrest [43].

ICU-acquired weakness leads to more time on the ventilator and in the ICU, higher rates of hospital-acquired infections, and poor outcomes for patients.

The profound loss of physical function and prolonged time in the ICU increases the demand for nurses as patients become dependent on total care. ICU-acquired weakness also increases failure to wean from the ventilator by 15.4 times and time on the ventilator by 20 days in sepsis patients [17].

Patients who develop ICU-acquired weakness also require more nurses and ICU staff to initiate mobility.

Here’s what Tara Dagesse, an ICU nurse from Connecticut, shared about caring for patients with ICU-acquired weakness:

I cared for a VV ECMO patient who had a severe ICU-acquired illness from sedation and immobilization practices at a former hospital. They had been extubated but were previously on heavy sedation.

I organized to get this patient hovered to a chair and set them up with bicycle pedals. I did this when other colleagues were available to help with lines, tubes, and wires during the hover, but the rest I did on my own. I hadn’t consumed much water that day because the break room was far from the patient’s room; I actually went to my own emergency department after my shift for a kidney stone from the lack of access to drinking water during that shift.

It had taken such significant effort and organization because of the patient’s severe neurologic and physical disability from the sedating medications that we gave them. Their lungs were recovering via the ECMO, but we irreparably damaged this person’s brain and body from sedation in the process.

It is not an easy task to mobilize such a patient, and even though I was determined, organized, and motivated, I ended up having to put my own basic human needs last to provide what I felt was a successful physical therapy day for my severely debilitated patient.

I was proud of the result for the patient, but I was unsustainably fighting the impenetrable heavy sedation culture. I had little support for my patients to be successful and have good outcomes from that program, and the oversedation culture directly affected my mental health.

When we would eventually have patients awaken, they had ‘dead eyes’ and were fully dissociated or otherwise neurologically withdrawn from the lasting effects of the continuous heavy sedation.

Families don’t question the need for sedation because ‘they seem comfortable,’ but this was an unfulfilling way to practice nursing. I did not go into this field to harm patients and that’s exactly what we were doing. I considered leaving nursing altogether like so many of my colleagues because I was told ‘the grass isn’t always greener.’

I eventually left that ICU after realizing I could no longer ethically care for patients in that environment.

I now work for a different hospital with better working conditions and unit-wide support for limiting sedation and keeping patients awake and active on the ventilators so they can be part of their own care and interact with their families.

It’s much more rewarding and exciting to care for critically ill patients that actually get better because we utilize the ABCDEF Bundle as it was intended.

RN Burnout and the ABCDEF Bundle

Despite the challenges that delirium and ICU-acquired weakness pose for nurses and patients, the prevailing ICU culture of automatic sedation and immobility drastically increases the risks of these conditions.

Mechanical ventilation is not an independent indication for continuous sedation [14], yet in most ICUs, sedative drips are routinely started after intubation on all patients.

Sedation increases the risk of delirium by 2.268 times [30] and the severity of delirium [29]. In one study, patients who were free of sedation spent 4.2 fewer days on mechanical ventilation and 3.67-9.09 fewer days in the ICU than those who received interrupted sedation [40].

Sedation also causes the quickest and highest rates of muscle loss compared to other causes of muscular atrophy [31].

Nurses have the burden of keeping patients safe from adverse events such as falls and unplanned extubations. However, nurses are also trained to increase and prolong the use of sedation, which ultimately exacerbates delirium and ICU-acquired weakness, increasing these adverse events and the demand for nurses to provide total care.

The ABCDEF Bundle guides ICU teams to avoid sedation, provide prompt mobility, and protect patients and nurses from the risks and burdens of delirium and ICU-acquired weakness using the following tools:

A: Assess, Prevent, and Manage Pain

B: Both Spontaneous Awakening Trials (SATs) and Spontaneous Breathing Trials (SBTs)

C: Choice of Analgesia and Sedation

D: Delirium: Assess, Prevent, and Manage

E: Early Mobility and Exercise

F: Family Engagement and Empowerment

A large study found that, on average, the ABCDEF Bundle decreased delirium by 25-50%, time on the ventilator and physical restraint use by 60%, 7-day mortality by 68%, discharges to anywhere but home by 36%, and readmission to the ICU by 46% [32].

Another study showed that ambulating patients within 36 hours after intubation increased their return to baseline functional status by 24% and decreased the duration of delirium by two days [37].

It’s also been shown that every additional 10 minutes of physical or occupational therapy decreases time in the hospital by 1.19 days [22].

At this point, it’s important to note that the ABCDEF Bundle requires interdisciplinary teamwork from physical therapists, occupational therapists, pharmacists, primary physicians, bedside nurses, respiratory therapists, and family to foster this all-encompassing, patient-centered approach [1].

The ABCDEF Bundle also fosters more team collaboration and improves the workplace environment. For example, one of the key tenets of these practices is mobility, which is a powerful tool for preventing and treating delirium and ICU-acquired weakness.

However, when patients are sedated, physical and occupational therapists are unable to provide meaningful therapy.

The main barriers to early mobility are sedation and agitation [41], which often leave nurses to struggle with agitated, delirious, and deconditioned patients by themselves.

But by allowing all disciplines to work together early on in an ICU admission to keep patients awake and mobile, most patients can remain cognitively and physically intact, which allows for more engagement in turning, mobility, and the care process in general.

Overall, as patients preserve their muscle mass and function at higher rates, less staff and equipment are likely to be required for mobility, and patients are likely to be liberated from the ventilator and transferred from the ICU far sooner.

This kind of collaboration, and the ability to ease workload offered by the ABCDEF Bundle, is demonstrated in the following case study:

A 32-year-old male patient with a history of obesity and polysubstance abuse was admitted to the ICU due to fentanyl overdose and aspiration pneumonia. He was intubated in the ICU and required a PEEP of 16 and 100%. A propofol intravenous drip was initiated at 30 mcg/kg/min. He became agitated and his propofol was then increased to 50 mcg/kg/min and he received midazolam pushes overnight.

The next day, the ICU team collaborated to investigate this patient’s condition and needs through the lens of the ABCDEF Bundle. As a result, it was realized that his agitation may be rooted in opioid and benzodiazepine withdrawal.

Enteral doses of opioid and benzodiazepine were given and propofol was discontinued. Six hours later, the patient was awake. He was given a whiteboard to write with and he remained awake but anxious at a RASS of +1 and CAM negative. While in bed, his oxygen saturations remained between 89% and 90%.

The following morning, the patient sat himself at the side of the bed with physical and occupational therapy. His oxygen saturations immediately increased to 93% while on a PEEP of 16 and 100%.

His anxiety and tension dissipated and he got himself to the bedside chair with the minimal assistance of line and tube management. He spent most of the day in the chair free of restraints and sedation at a RASS of 0 during the following three days before being successfully extubated. He was independently walking around the ICU and transferred from the ICU shortly after.

Unfortunately, the reality is that without utilizing the ABCDEF Bundle approach, this patient likely would have remained on high-dose propofol and would have been at high risk of delirium and ICU-acquired weakness.

The nurses attending to him would have also been saddled with the risks and challenges of turning a 350-pound flaccid body for days or even weeks.

His muscle loss from myotoxic propofol [46] and immobility would have led to severe and prolonged dependence on the ventilator and nursing staff. Delirium he would likely experience could result in agitation, failed awakening trials, more stress and monitoring, and days to weeks longer in the ICU.

The challenging irony is that although adequate ICU staffing ratios are required to practice the ABCDEF Bundle [3], failing to practice it puts even more strain on staffing ratios through increased time on the ventilator, time in the hospital, manpower to care for patients, readmissions to the ICU and hospital, health care costs, and the burnout of nurses.

All things considered, one of the most powerful tools to prevent and treat delirium and ICU-acquired weakness is mobility.

Because of this, many nurses are expected to mobilize critically ill patients, but unfortunately, they are often untrained and unsupported in mobilizing them.

This leaves nurses with the burden of continuing to provide exhaustive total care and monitoring to confused and deconditioned patients for prolonged periods of time without the ability to truly treat and resolve delirium and ICU-acquired weakness.

Luckily, the ABCDEF Bundle offers one of the most effective ways to advocate for adequate staffing ratios, as delirium increases hospitalization costs by 39% [27], ICU-acquired weakness increases costs by 30.5% [19], and the ABCDEF Bundle can also decrease health care costs by at least 30% [20].

A nurse-led early mobility initiative in a medical ICU resulted in a 57% decrease in mortality, a 33% decrease in time on the ventilator, and was projected to have saved $2,070,000 that year [13].

Another ICU found their nursing-led mobility initiative increased mobility by 43% and resulted in a 50-100% decrease in hospital-acquired complications [44].

These stats are useless if the resources needed to mobilize patients are not available to nurses. I don’t doubt their efficacy − but most ICUs just do not have the resources (specifically staff) to safely mobilize their patients.

Why is this? We would never deprive surgeons of soap and water to scrub with before surgery, as we have data that clearly shows the benefits of hand hygiene for infection prevention. If we have data that shows early mobilization in the intensive care setting results in better patient outcomes, why then do hospitals deprive their staff of the resources they need to provide their patients with high quality care?

− Allison Diburro, Massachusetts

Still, the fact is many nurses may be unaware of the increased burden of sedation and immobility, and what is “normal” and familiar is often comfortable and accepted as unavoidable.

These practices may even be preferred, but nonetheless, even when unaware of the risks of these interventions, nurses are subjected to dealing with the psychological toll of seeing frequently poor outcomes for their patients.

Patient autonomy and nonmaleficence are core principles of nursing ethics [16], but sedation deprives patients of their voice and their autonomy.

Depriving patients of the ability to participate in end-of-life decision making can lead to prolonged treatments and severe ethical turmoil for nurses.

Nurses often struggle with the idea of providing treatments that they perceive as prolonging suffering or doing harm to patients [28].

We used to do things for patients and now we do things to patients. I used to leave work and had a sense that I made a difference. I missed time from family and friends for a reason, but now I have those moments less and less. We have the technology to do more and so we do more for a prolonged amount of time and we start to see the slow decline of a human into a failing body.

When you add sedation, you remove the patient’s voice, and delirium amplifies this tenfold. The patient can no longer advocate for themselves and families are left in moral distress deciding what to do.

− Roni Kelsey, Washington

Nurses that know the harm of sedation and immobility, but lack support from their teams, face unbearable moral injury when unable to provide optimal evidence-based care for their patients.

They are forced to witness and struggle to treat the often preventable harm of delirium and ICU-acquired weakness [10], and when they know the life-long damages and increased mortality survivors will face from these conditions after the ICU, they are left with severe ethical turmoil [6].

I left my critical care training position due to a toxic work culture and my own moral distress of watching patient after patient be put on a pathway to delirium.

My introduction to the ABCDEF Bundle occurred on the final day of didactic training. The only motivation provided for adhering to the bundle was that we had to demonstrate proper charting of the elements or else face consequences – there was no explanation of the inherent purpose or value of the bundle itself.

In practice, I observed patients appearing significantly oversedated, with RASS assessments that seemed inconsistent with the clinical presentation. Spontaneous awakening trials were attempted sporadically and incompletely. When I raised concerns regarding these issues, the responses typically referenced patient comfort, with explanations such as ‘it’s not nice to have a tube down your throat’ and ‘the patient needs to sleep.’ Potential consequences of oversedation, such as delirium or delayed weaning, were not discussed.

I went into the ICU excited about being challenged with complex medical puzzles. But in the end, the moral distress of putting patients down the path of deconditioning, oversedation, delirium, and long-term consequences, such as permanent disability, was too great for me to participate any longer.

− Annie, California

I often shared awake and walking concepts with my coworkers and attempted to convince others to remove restraints, use other forms of treatment for agitation, rather than sedation, and advocate for extubation.

Repeatedly my attempts were shut down. I witnessed so much dehumanizing care that caused an amount of moral distress through which I could no longer work in the ICU. My own patients benefited from the removal of restraints, being allowed to be awake, move freely, and make their own end-of-life decisions while on a ventilator. I could not understand why others would not be willing to do the same.

− Anonymous ICU nurse from Missouri

Nurses work incredibly hard for their patients, but they need to have as many calm, communicative, compliant, and functional patients as possible in order to ease their workload.

It is time for them to have real human connection and communication with the souls that they are diligently serving, and in order to do this, they must practice the ABCDEF Bundle, which enables optimal teamwork, collaboration, and support of nurses.

They also deserve to know they are giving their patients the best chance to survive and thrive and have the reward of watching patients succeed and walk out of the ICU doors [9].

When we started the ICU Liberation Bundle in our ICU one of the nurses was so excited to help his intubated patient have a ‘normal’ bowel movement in the commode instead of a loose stool in a bed pan. He was able to give his patient back some dignity and felt like while he did more work, it was more rewarding work.

− Roni Kelsey, Washington

As we deal with this current nursing shortage, it’s important for us to make use of evidence-based sedation and mobility practices, which can lead to improved outcomes for both nurses and patients [11].

We must support nurses in their quest to master the ABCDEF Bundle so they can better handle their workload, workplace environment, bed flow, human connection, job satisfaction, and burnout [8].

The whole point of doing the ABCDEF Bundle is not to do the ABCDEF Bundle. It’s to facilitate better and more nurse-rewarding outcomes. ABCDEF is not the goal. The goal is what the ABCDEF elements bring.

As someone who has done trauma, ER, MICU, COVID, and now does a lot of surgical heart work, the ABCDEF Bundle gets my patients to where I enjoy the care.

Getting my patients awake so they can get better gives me satisfaction and joy. Getting them awake to communicate with loved ones is hard work but it feels better than just turning every two hours for sedated, flaccid, and atrophying bodies.

− James Fletcher, California

Do you want to turn your ICU into an Awake and Walking ICU? Contact us today to find out how we can guide you through the transformation.

References:

- Bailey, P. P., Miller, R. R., 3rd, & Clemmer, T. P. (2009). Culture of early mobility in mechanically ventilated patients. Critical Care Medicine, 37(10 Suppl), S429–S435.

- Bélanger, L., & Ducharme, F. (2011). Patients’ and nurses’ experiences of delirium: a review of qualitative studies. Nursing in critical care, 16(6), 303–315.

- Boehm, L. M., Dietrich, M. S., Vasilevskis, E. E., Wells, N., Pandharipande, P., Ely, E. W., & Mion, L. C. (2017). Perceptions of Workload Burden and Adherence to ABCDE Bundle Among Intensive Care Providers. American Journal of Critical Care, 26(4), e38–e47.

- Breitbart, W., Gibson, C., & Tremblay, A. (2002). The delirium experience: delirium recall and delirium-related distress in hospitalized patients with cancer, their spouses/caregivers, and their nurses. Psychosomatics, 43, 183–194.

- Taylor, C. (2023). Intensive care unit-acquired weakness. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine, ISSN 1472-0299.

- Dayton, K. (2020). Episode 39: Ethical Turmoil. Walking Home From The ICU.

- Dayton, K. (2021). Episode 82: Burnout. Walking Home From The ICU.

- Dayton, K. (2022). Episode 114: From the Eyes of a Travel Nurse. Walking Home From The ICU.

- Dayton, K. (2023). Episode 118: Mobility Saves Lives During ECMO. Walking Home From The ICU.

- Dayton, K. (2023). Episode 156: Nurses Are Willing, but Unsupported and Untrained in Practicing the ABCDEF Bundle. Walking Home From The ICU.

- Dayton, K. (2023). Episode 146: Success Stories from ICU Revolutionists. Walking Home From The ICU.

- Dziegielewski, et al. (2021). Characteristics and resource utilization of high-cost users in the intensive care unit: a population-based cohort study. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1312).

- Early Mobilization of the Ventilated Patient. www.aacn.org. (n.d.)

- Eikermann, M., Needham, D. M., & Devlin, J. W. (2023). Multimodal, patient-centred symptom control: a strategy to replace sedation in the ICU. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 11(6), 506–509.

- Ely, W., et al. (2004). Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. Journal of the American Medical Association, 291(14).

- Epstein, B., & Turner, M. (2015). The Nursing Code of Ethics: Its Value, Its History. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 20(2), 4.

- Garnacho-Montero, J., et al. (2005). Effect of critical illness polyneuropathy on the withdrawal from mechanical ventilation and the length of stay in septic patients. Critical Care Medicine, 33(2).

- Guttormson, J. L., Calkins, K., McAndrew, N., Fitzgerald, J., Losurdo, H., & Loonsfoot, D. (2022). Critical Care Nurse Burnout, Moral Distress, and Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A United States Survey. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Cardiopulmonary and Acute Care, 55, 127–133.

- Hermans, G., et al. (2014). Acute and long-term outcomes of ICU-acquired weakness: a cohort study and propensity matched analysis. Critical Care, 18.

- Hsieh, S., et al. (2019). Staged implementation of ABCDE bundle improves patient outcomes and reduces hospital costs. Critical Care Medicine, 47(7).

- Jakobsson, J., Axelsson, M., & Ormon, K. (2020). The Face of Workplace Violence: Experiences of Healthcare Professionals in Surgical Hospital Wards. Nursing Research and Practice.

- Jenkins, A. S., Isha, S., Hanson, A. J., Kunze, K. L., Johnson, P. W., Sura, L., Cornelius, P. J., Hightower, J., Heise, K. J., Davis, O., Satashia, P. H., Hasan, M. M., Esterov, D., Worsowicz, G. M., & Sanghavi, D. K. (2023). Rehabilitation in the Intensive Care Unit: How Amount of Physical and Occupational Therapy Impacts Patients’ Functionality and Length of Hospital Stay. PM&R: The Journal of Injury, Function, and Rehabilitation, 10.1002/pmrj.13116. Advance online publication.

- Judge, K. S., Menne, H. L., & Whitlatch, C. J. (2010). Stress Process Model for Individuals With Dementia. The Gerontologist, 50(3), 294–302.

- Kwon, E., & Choi, K. (2017). Case-control study on risk factors of unplanned extubation based on patient safety model in critically ill patients with mechanical ventilation. Asian Nursing Research, 11(1).

- McDonnell, S., & Timmins, F. (2012). A quantitative exploration of the subjective burden experienced by nurses when caring for patients with delirium. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 2488–2498.

- Meier, M., et al. (2017). Incidence, correlates and outcomes associated with falls in the intensive care unit: a retrospective cohort study. Critical Care and Resuscitation, 19(4).

- Milbrandt, E. B., et al. (2004). Costs associated with delirium in mechanically ventilated patients. Critical Care Medicine, 32(4), 955–962.

- Nazari, F., Chegeni, M., & Shahrbabaki, P. M. (2022). The relationship between futile medical care and respect for patient dignity: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing, 21(1), 373.

- Ortiz, D., Lindroth, H. L., Braly, T., Perkins, A. J., Mohanty, S., Meagher, A. D., Khan, S. H., Boustani, M. A., & Khan, B. A. (2022). Delirium severity does not differ between medical and surgical intensive care units after adjusting for medication use. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 14447.

- Pan, Y., Yan, J., Jiang, Z., Luo, J., Zhang, J., & Yang, K. (2019). Incidence, risk factors, and cumulative risk of delirium among ICU patients: A case-control study. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 6(3), 247–251.

- Parry, S. M., & Puthucheary, Z. A. (2015). The impact of extended bed rest on the musculoskeletal system in the critical care environment. Extreme Physiology & Medicine, 4, 16.

- Pun, B., Balas, M., Barnes-Daly, M., Thompson, J., Aldrish, J., Barr, J., Byrum, D., Carson, S., Devlin, J., Engel, H., Esbrook, C., Hargett, K., Harmon, L., Hielsberg, C., Jackson, J., Kelly, T., Kumar, V., Millner, L., Morse, A., Perme, C., Posa, P., Puntillo, K., Schweickert, W., Stollings, J., Tan, A., McGowan, L., & Ely, W. (2019). Caring for Critically Ill Patients with the ABCDEF Bundle: Results of the ICU Liberation Collaborative in Over 15,000 Adults. Critical Care Medicine, 47.

- Ramírez-Elvira, S., Romero-Béjar, J. L., Suleiman-Martos, N., Gómez-Urquiza, J. L., Monsalve-Reyes, C., Cañadas-De la Fuente, G. A., & Albendín-García, L. (2021). Prevalence, Risk Factors and Burnout Levels in Intensive Care Unit Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11432.

- Salluh, J., et al. (2015). Outcome of delirium in critically ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal, 350.

- About ICU Liberation. www.sccm.org. (n.d.)

- Schmitt, E. M., Gallagher, J., Albuquerque, A., Tabloski, P., Lee, H. J., Gleason, L., Weiner, L. S., Marcantonio, E. R., Jones, R. N., Inouye, S. K., & Schulman-Green, D. (2019). Perspectives on the Delirium Experience and Its Burden: Common Themes Among Older Patients, Their Family Caregivers, and Nurses. The Gerontologist, 59(2), 327–337.

- Schweickert, W. D., Pohlman, M. C., Pohlman, A. S., Nigos, C., Pawlik, A. J., Esbrook, C. L., Spears, L., Miller, M., Franczyk, M., Deprizio, D., Schmidt, G. A., Bowman, A., Barr, R., McCallister, K. E., Hall, J. B., & Kress, J. P. (2009). Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 373(9678), 1874–1882.

- Seiler, et al. (2021). Delirium is associated with an increased morbidity and in-hospital mortality in cancer patients: results from a prospective cohort study. Cambridge University Press.

- Stenwall, E., Sandberg, J., Jönhagen, M. E., & Fagerberg, I. (2007). Encountering the older confused patient: Professional carers’ experiences. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 21, 515–522.

- Strøm, T., Martinussen, T., & Toft, P. (2010). A protocol of no sedation for critically ill patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a randomised trial. The Lancet, 375(9713), 475–480.

- The TEAM Study Investigators and the ANZICS Clinical Trials Group, Hodgson, C. L., Bailey, M., Bellomo, R., Brickell, K., Broadley, T., Buhr, H., Gabbe, B. J., Gould, D. W., Harrold, M., Higgins, A. M., Hurford, S., Iwashyna, T. J., Serpa Neto, A., Nichol, A. D., Presneill, J. J., Schaller, S. J., Sivasuthan, J., Tipping, C. J., Webb, S., & Young, P. J. (2022). Early Active Mobilization during Mechanical Ventilation in the ICU. New England Journal of Medicine, 387(19), 1747–1758.

- Tilouche, N., et al. (2018). Delirium in the intensive care unit: incidence, risk factors, and impact on outcome. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine, 22(3).

- Topp, R., et al. (2002). The effect of bed rest and potential of prehabilitation on patients in the intensive care unit. AACN Clinical Issues, 13(2).

- Walking Toward Discharge “WTD”. www.aacn.org. (n.d.)

- Wu, G., Soo, A., Ronksley, P., Holroyd-Leduc, J., Bagshaw, S. M., Wu, Q., Quan, H., & Stelfox, H. T. (2022). A Multicenter Cohort Study of Falls Among Patients Admitted to the ICU. Critical Care Medicine, 50(5), 810–818.

- Lönnqvist, P. A., Bell, M., Karlsson, T., Wiklund, L., Höglund, A. S., & Larsson, L. (2020). Does prolonged propofol sedation of mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients contribute to critical illness myopathy?. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 125(3), e334–e336.