Throughout the pandemic, it’s become increasingly obvious that the lack of evidence-based ICU protocols is having a devastating effect on ICU patient care.

Over the last two years, I’ve seen countless examples of this, and it breaks my heart because most of these tragedies are totally preventable.

One of the most poignant examples of this can be found in the case of a COVID patient who met her demise as a result of these outdated practices.

Her name was Sally, and this is her story.

How Outdated ICU Protocols Spelled the End for Sally

Sally was a 66-year-old female with a history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, and morbid obesity who had two children, six grandkids, and lived independently.

She was admitted to the hospital on the 14th day after the onset of COVID symptoms and ended up on the medical floor for two weeks on strict bed rest.

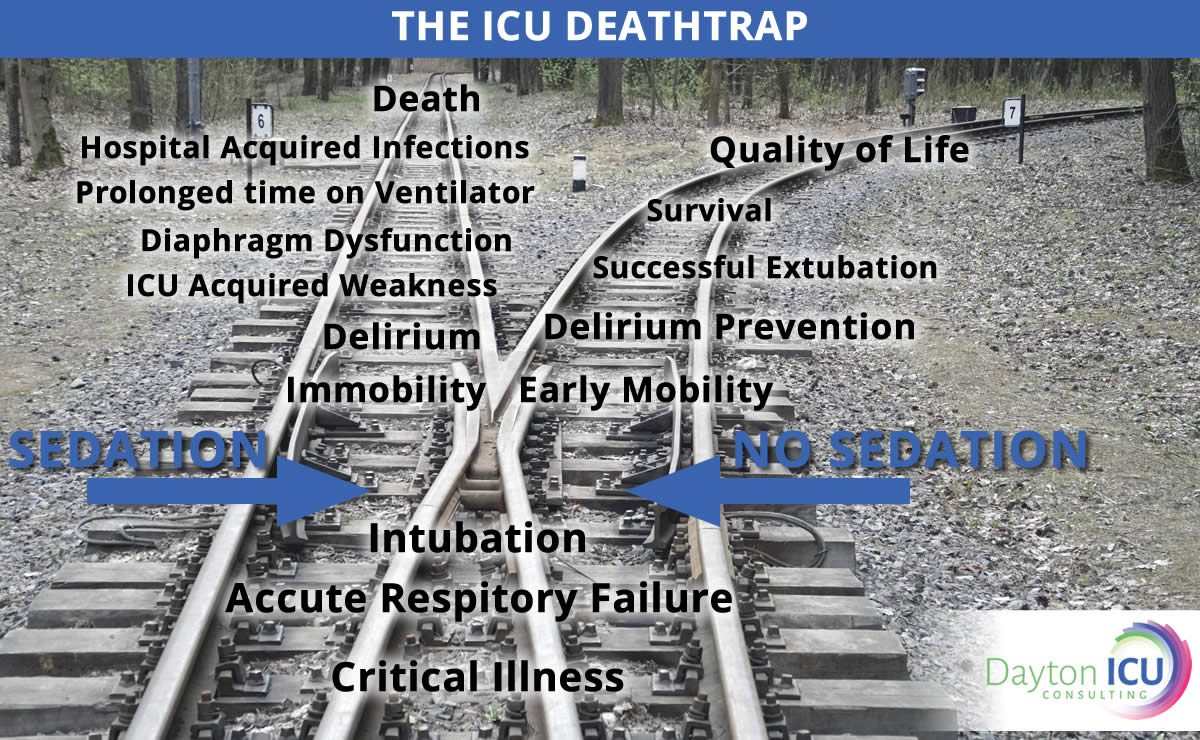

Sally ended up in the ICU due to worsening acute respiratory failure from COVID pneumonia, and upon her arrival, she was intubated and automatically deeply sedated.

Initially, Sally required ventilator settings of Assist Control, a PEEP of 18, and a FIO2 of 100%. She spent the following 42 days on several drugs, including clinamex, propofol, fentanyl, norepinephrine, and vasopressin.

When Michelle became her nurse on day 42, Sally’s ventilator settings were changed to Assist Control, a PEEP of 10, and a FIO2 of 60%. She was put on propofol (65mcg/kg/min), fentanyl (200mcg/hr), dexmedetomidine (1.4 mcg/kg/hr), vasopressin (0.02 units/min), and norepinephrine (10 mcg/min).

Sally also had a RASS score of -5, a stage 3 coccyx pressure injury, and a bilateral foot drop, and had not had a sedation vacation or mobility session for the entire 42 days of mechanical ventilation and deep sedation.

Upon starting her shift, Michelle immediately weaned off the sedation and was able to discontinue vasopressin and decrease norepinephrine. At this point, Sally’s ventilator settings were decreased to a PEEP of 5, and a FIO2 of 70%.

Sally soon arose and Michelle started to make plans with her to video chat with her family.

She was able to do a breathing trial on CPAP for 45 minutes and then became tachypneic and fatigued. At 11:50 a.m. Michelle was informed she would be receiving a new patient and was to hand Sally off to a different nurse.

The next nurse was mortified and very nervous to find Sally awake and aware.

Michelle explained that Sally was trying to communicate by nodding her head for yes and shaking her head for no, and she was calm and compliant. She also informed the nurse that Sally was exhausted from breathing independently for 45 minutes and was getting rest on Assist Control.

As Michelle was receiving the report for her next patient, she saw Sally’s new nurse heading towards the room with propofol, fentanyl, and dexmedetomidine.

Michelle ran to the nurse and said, “Wait! What are you doing with those?” Sally’s new nurse said, “She looks tired. I’m going to give her some rest.”

Michelle tried to explain the reality of those medications, but the nurse was not receptive to the information. Unfortunately, she was unable to protect calm, awake, communicative, and intubated Sally from being sedated again.

Two weeks later, Michelle ended up being Sally’s nurse again. Her ventilator settings had decreased to a PEEP of 5, and a FIO2 of 40%. Sally had been deeply sedated for the two preceding weeks without any sedation vacation or mobility sessions.

Michelle discontinued all of the sedation once again. Around this time, the medical team convened to discuss end-of-life care for Sally, and her family refused to consent to a tracheostomy.

Michelle rallied some nursing students together and had Sally dangling at the side of the bed. Then, for the first time during her 56-day admission, Sally’s family was allowed to be with her.

The next day, Sally was prematurely extubated. Her diaphragm dysfunction caused hypoventilation, she developed hypercarbia, respiratory failure, and died 12 hours after extubation.

If you want to hear more about Sally’s story, straight from her nurse, Michelle Schmidt, you can listen to Episode 94 of my Walking Home From The ICU podcast.

What Went Wrong: The Perspective of a Patient Care Advocate

After considering all the details of how Sally was treated in the ICU, there are several unanswered questions, and I have many concerns with how her case was handled.

For instance, it’s concerning that Sally, a 66-year-old obese patient with COVID pneumonia, was on strict bedrest for two weeks, as this likely contributed to her deterioration and ICU admission.

There is evidence that immobility may contribute to the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and the loss of respiratory muscle function. One study found that a week of bedrest can actually result in a loss of up to 40% of lean muscle.

The inflammatory repercussions of immobility are certainly dangerous during an inflammatory disease such as COVID-19. Another study showed immobility increases the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species with subsequent muscle proteolysis, which promotes overall muscle loss.

Another thing I take issue with is the way Sally was medicated during her stay in the ICU, so I want to provide some context by looking a bit deeper at each one of her medications.

Risks and Considerations for Sally’s Medications

Clinamex

It is unclear why Sally was on clinamex instead of having a feeding tube to provide nutrition through her gut. During mechanical ventilation, if you want to provide optimal nutrition, enteral nutrition should be the preferred method.

Sally had a high risk of malnutrition, and there’s evidence to show that this could have increased her risk of dying.

Propofol

Prolonged use of propofol causes diaphragm dysfunction, neuromuscular connection, insulin resistance, and is likely myotoxic. Propofol also causes hypotension and increases the risk of needing vasopressor support. In addition, it prevents REM sleep and increases the risk of delirium.

The maximum dose of propofol should be no more than 50mcg/kg/min. It is unclear why she was receiving such a high dose of propofol, and this likely induced hypotension, which caused her to receive vasopressors.

Fentanyl

Fentanyl increases the risk of delirium and opioid dependence. One study showed patients on mechanical ventilation likely do not need opioids, or only require low doses of them, and it found that increased doses of fentanyl can actually prolong time on the ventilator.

It is unclear why Sally was on such high doses of continuous fentanyl.

Dexmedetomidine

Dexmedetomidine can be a great medication for temporary light sedation. However, it also comes with the risk of bradycardia and hypotension.

It is unclear why this drug was being administered in addition to high doses of propofol and fentanyl while Sally was also being given vasopressors.

Vasopressin

Vasopressin may induce several adverse effects, including arrhythmias, mesenteric ischemia, chest pain, coronary artery constriction, bronchial constriction, and myocardial infarction.

Norepinephrine

Norepinephrine also has a long list of side effects. It heightens the risk of bradycardia, increases systemic vascular resistance, which increases afterload and overall myocardial oxygen demand, and it can even increase pulmonary vascular resistance, which is especially difficult when there is pulmonary hypertension.

Both vasopressin and norepinephrine can also increase the risk of ICU-acquired weakness.

Vasopressors can be life-saving, but they should only be used when essential for survival, and for as short a duration as possible.

It’s likely that Sally received these vasopressors for over 46 days, solely because she was on high doses of sedatives that cause hypotension. It is also likely that she had a central line for a prolonged period due to vasopressor use, which is probably rooted in unnecessary prolonged deep sedation. This increased her risk of central line infections and mortality.

Ultimately, this automatic deep sedation and immobility led Sally to develop foot drop and pressure injuries, which, according to at least one study, are independent predictors of mortality in the ICU.

ICU-Acquired Weakness and Diaphragm Dysfunction

Aside from complications with her medications, Sally’s demise also had a lot to do with the fact that she was suffering from ICU-acquired weakness and diaphragm dysfunction.

For example, there’s evidence to show that ICU-acquired weakness actually increases the risk of death by eight times.

According to one study, the 2-year survival rate for all ICU survivors is 67%, and the

survival rate without ICU-acquired weakness or diaphragm dysfunction is 79%. At the same time, the study showed the survival rate with ICU-acquired weakness alone is 46%, whereas the survival rate with ICU-acquired weakness and diaphragm dysfunction is 36%.

Sally suffered from this perfect storm of ICU-acquired weakness and diaphragm dysfunction, on top of having to deal with sedation, immobility, mechanical ventilation, vasopressors, and altered nutritional status, all of which was exacerbated by critical illness and an inflammatory disease process.

She had not used her diaphragm or respiratory muscles for over 50 days, and sustaining her own ventilation over prolonged periods of time was not feasible after such a course.

By that point, with a PEEP of 5, and a FIO2 of 40%, her respiratory failure and death at that moment were not from COVID, but from ICU-acquired weakness and diaphragm dysfunction.

It Doesn’t Have to Be This Way

Sadly, this was likely all preventable had evidence-based best practices from the ABCDEF Bundle been implemented from the very beginning.

Had Sally been treated for COVID-19 using evidence-based sedation and mobility practices, she may have been spared:

- Death

- Delirium

- Isolation

- Foot-drop

- Pressure Injury

- Immeasurable suffering

- ICU-acquired weakness

- Familial regret, loss, and grief

- Prolonged time on the ventilator

- Preventable extra weeks in the ICU

In addition to Sally’s suffering, the ICU may have been spared:

- Weeks of ICU care, as well as bed/ventilator/staff occupancy

- Healthcare costs associated with these preventable weeks in the ICU

- The burden of poor outcomes and death that contribute to staff burnout and poor staff retention

- Avoidable labor, such as constant sedation and vasopressor IV bag exchanges, turning, wound care, oral care, ventilator checks, breathing

- treatments, the strain of bathing and changing bed sheets with a flaccid adult patient, and constant adjustments of vasopressors, among other things

At the end of the day, outdated ICU protocols are costly to the healthcare system, clinicians, families, and patients, but it doesn’t have to be this way.

By implementing the evidence-based practices in the ABCDEF Bundle, we can mitigate or eliminate these dire costs by saving and preserving lives, while decreasing the burden on our healthcare system.

If you want to know more about how I can help you advocate for evidence-based ICU protocols, or the ICU where your family member has been admitted, please don’t hesitate to set up a complementary 15-minute appointment with me.