I have to admit, I wasn’t a fan of awakening trials at first.

During my first two years in an Awake and Walking ICU, we rarely initiated sedation, so the need to turn it off wasn’t a struggle for us.

When sedation was necessary, we simply turned it off when we deemed it unnecessary.

It wasn’t until my third travel assignment – three years into my critical care journey – that I encountered awakening trials.

“Here, we do this annoying thing at 5 a.m.,” they said. “You turn off sedation, and when you see them move, you turn it back on. That indicates they haven’t had a stroke and can tolerate the ventilator. Just chart ‘failed awakening trial’ in this SAT category.”

At the time, it made no sense to me.

What was the objective? This wasn’t a full neuro exam.

Why did patients react this way? And what did they need?

Despite my confusion, I had been worn down by demeaning responses to my previous questions about sedation, so I held my tongue and followed orders.

However, the stress of conducting these “awakening trials” at the end of my night shift was overwhelming.

Often, I was alone, unaware of how or when the patient would emerge from sedation.

Patients might remain quiet and then suddenly become wild just as I was attending to others.

When this happened, patients often tried to pull out their tubes, and in these instances, I had been directed to turn the sedation back on.

At the time, this baffled me, as I had already seen hundreds of intubated patients who were fully awake, calm, compliant, and even unrestrained.

So, why were these patients so “tube intolerant?” What made them different?

And why was this experience so much more challenging than in my first ICU?

What I Wish I’d Known About Awakening Trials

Like all ICU clinicians, I became a nurse because I’m passionate about saving and preserving people’s lives.

However, after starting my work as a nurse in an Awake and Walking ICU, and then working in several conventional ICUs, I became quite disheartened, as I could see that ICU culture has created many barriers to providing the absolute best evidence-based care.

With that in mind, here’s what I wish I’d known about awakening trials back then:

Delirium Increases the Risk of Self-Extubation

Delirium can increase the risk of self-extubation by 11.6 times, continuous sedation raises the risk of delirium by 216%, and more sedation correlates with increased severity of delirium.

Most patients I encountered in my first ICU remained awake, calm, and unrestrained because they were free of sedation after intubation.

They were quickly allowed to wake up so they could become oriented to their condition and tubes, which helped keep their movements safe. They could also connect with family, communicate their needs, and get quality sleep – all factors that mitigate delirium.

Patients who are not delirious can better cope with the endotracheal tube, as they can understand its necessity for survival, and they can actually articulate their needs and help respiratory therapists optimize their comfort settings.

Awakening Trials Aren’t Just an On/Off Switch for Sedation

In the early ‘90s, spontaneous breathing trials showed that patients who had sedation and the ventilator turned off to test their ability to be off of ventilator support did significantly better, and this led to the development of spontaneous awakening trials.

Over time, words like trials, interruption, break, holiday, and vacation became common in ICU sedation discussions.

Unfortunately, these terms suggest a temporary break from sedation rather than a re-evaluation of its necessity, which encourages clinicians to continue using these kinds of outdated practices.

The Purpose of Awakening Trials Is to Assess Sedation Needs

In the Awake and Walking ICU, we initiated this assessment promptly after intubation – unless specific conditions indicated that sedation was necessary.

We allowed patients to promptly awaken and communicate their needs via pen and paper, or even by texting on cell phones.

If a patient was at a RASS of +3 or +4, we employed light sedation like dexmedetomidine to calm them down to a RASS of 0 or +1, where we could safely facilitate mobilization and communication.

Our goal was to attempt to discontinue the daily use of sedation.

For patients unable to oxygenate with movement due to severe ARDS, for instance, we would stop sedation each day to gauge their oxygen saturation during movement, and if they maintained appropriate levels, sedation would remain off, allowing us to focus on mobility.

In any case, awakening trials are not just used to determine if a patient is ready to extubate.

Their main purpose is to ensure patients are only sedated when necessary, pushing for sedation cessation rather than just a brief interruption.

The ABCDEF Bundle’s Objective Is Critical

The aim of the ABCDEF Bundle is to keep patients as awake, communicative, autonomous, and mobile as possible, even early on after ICU admission and intubation.

And if we as clinicians want to provide the best possible care for our patients, then working toward that objective is absolutely critical.

As Dr. Wes Ely says, “Awakening trials are for the rehumanization of the patient,” which means we allow them to move, communicate, and be involved in their journey through the ICU.

When to Do Awakening Trials

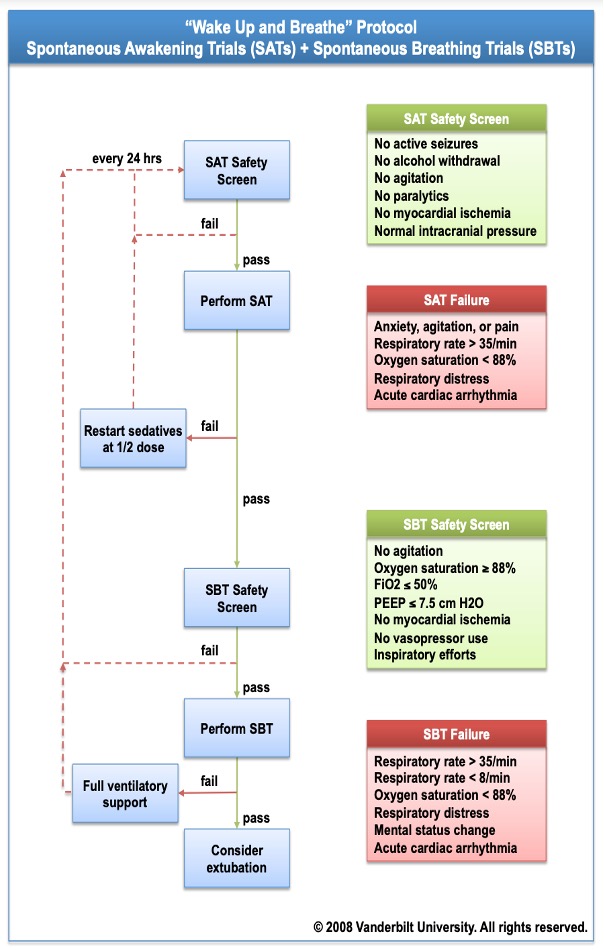

The image above shows a common SAT and SBT algorithm.

These prompts show valuable guidelines to help clinicians critically think, but I have witnessed in my own practice and within dozens of other teams that these prompts are misinterpreted.

For example, agitation is listed as criteria for a failed awakening trial. Yet we are seeing at the bedside that a RASS of +1, which indicates that a patient is restless, is being charted as agitated, the awakening trial is deemed a failure, and sedation is being resumed.

Instead, this kind of protocol should use objective RASS scores, with a RASS of >+2 indicating a failed SAT.

At any rate, I suspect that having SAT and SBT criteria on this same page has led to the myth that SATs are for SBTs.

However, SATs should be done as soon as we suspect there is no longer an indication for sedation.

For many patients, this can and should be done once the paralytics for intubation are no longer in effect. We do NOT need to wait until we are doing a breathing trial to do an awakening trial.

And despite what I was told in that one ICU, movement does not indicate a failed awakening trial.

How to Respond to an Actual Failed Awakening Trial

If an awakening trial is actually deemed a failure, sedation should be resumed, but at half the previous dose.

However, despite this being a part of most hospital policies, this strategy is often overlooked in clinical practice.

At any rate, after an awakening trial, resuming sedation at the same dose or higher undermines the goals of maintaining patient wakefulness, autonomy, and mobility.

One randomized controlled trial showed that the awakening trial group ultimately received more sedation than the control group, which never received any “breaks” from sedation.

All things considered, just because awakening trials are required in the charting or even mentioned in rounds does not mean that they are being done properly.

A Strategic Approach to Stopping Sedation

Awakening trials are often late, inconsistent, poorly executed, or yield low success rates due to insufficient education and strategy.

My initial dread of these trials stemmed from the stress of managing a delirious, agitated patient alone during night shifts, which basically set things up to fail.

In any case, all clinicians in the ICU must have a shared understanding of the risks associated with sedation and immobility.

Together, we should aspire to keep patients awake, communicative, autonomous, and mobile shortly after intubation.

And when sedation is indicated, it’s essential for our teams to collaborate and adopt a strategic approach to help patients wake up as soon as possible and acclimate to the endotracheal tube.

Just as importantly, whenever a patient first opens their eyes, their loved ones should be present at the bedside.

These family members play a crucial role in maintaining a calm environment, helping the patient understand the tube, assisting with communication through writing or texting, or simply being there as a reassuring presence.

What’s more, ICU teams need to be competent in managing ventilator settings, securing the tube, and conducting pain assessments, all of which aid patients in adjusting to intubation.

And if a patient shows signs of delirium, the nurse should be prepared to call in a “delirium SWAT team,” which includes physical therapists, occupational therapists, and speech therapists.

Moreover, rather than resuming sedation at full dosage, nurses should strive to keep patients awake enough to engage in physical therapy and occupational therapy, working toward sitting on the edge of the bed and, hopefully, standing or walking.

This approach often results in patients becoming calmer and more adjusted to their surroundings, and it makes it easier for RNs to manage patients after mobility efforts.

Final Words

The “vacation” time for sedation needs to end.

We must shift our semantics, culture, and perspective from automatic sedation for all and a quick on/off approach to actively working toward avoiding and minimizing sedation usage unless it’s absolutely necessary.

What’s more, as I’ve pointed out countless times, like on Episode 4 of my Walking Home From The ICU podcast, it’s crucial for clinicians to recognize that sedation is NOT sleep.

Among other things, prolonged sedation increases the risks of delirium, ICU-acquired weakness, mortality, long-term brain injury, and PTSD.

It’s also important to point out that resuming sedation in response to signs of discomfort does not adequately address agitation or anxiety, and it often plunges patients deeper into traumatic delirium.

All things considered, it’s time to move beyond the SAT and SBT culture of the 1990s and start embracing the critical thinking and interdisciplinary collaboration that are required to foster the development of Awake and Walking ICUs.

Do you want your team to master the ABCDEF Bundle? If you’re ready to create an Awake and Walking ICU, please don’t hesitate to book a free consultation.

When patients are so ill that they require a ventilator in the ICU, the antiquated approach of heavy sedation and immobilization should be avoided in order to help prevent the immense burden of physical and cognitive disabilities suffered during survival. To understand this better, listen to Walking Home From The ICU. You will see what ICU consultant Kali Dayton provides to your team.

When patients are so ill that they require a ventilator in the ICU, the antiquated approach of heavy sedation and immobilization should be avoided in order to help prevent the immense burden of physical and cognitive disabilities suffered during survival. To understand this better, listen to Walking Home From The ICU. You will see what ICU consultant Kali Dayton provides to your team.